Collection Guide: The Viennese School

Drawing Matter’s collection of Viennese drawings from the 19th and early 20th century includes works by Franz Jakob Kreuter, Otto Wagner, Josef Hoffmann, Otto Schönthal, Emil Hoppe, and Friedrich Ohmann, among others. It was a time of great technological advance, social upheaval, cultural revolt, and changing attitudes to design. Considered as a group, the drawings speak to the challenges confronting Viennese society at this time, the expanding city and vigorous polemics for new building materials and methods.

Drawings by these Viennese architects are widely distributed. The majority of Kreuter’s work is housed in the Historic Archive of the City of Cologne; the Wien Museum, has substantial collections of drawings by both Wagner and Hoffmann; while works by Otto Schönthal, Emil Hoppe, and Friedrich Ohmann are spread across Austria, with significant holdings in the Museum for Applied Arts, the Wien Museum, and the Academy of Fine Arts, all in Vienna.

Drawing Matter is hugely privileged to have been working with Professor Boyd Whyte; we are very grateful to him for unmatched knowledge and experience, so generously shared in the text below.

ON THE VIENNESE SCHOOL AND THEIR APPROACH TO DRAWING, READ HERE 11 TEXTS, PUBLISHED ON DRAWING MATTER SINCE 2013.

TO ACCESS THE DRAWING MATTER COLLECTION OF THE VIENNESE SCHOOL, CLICK HERE.

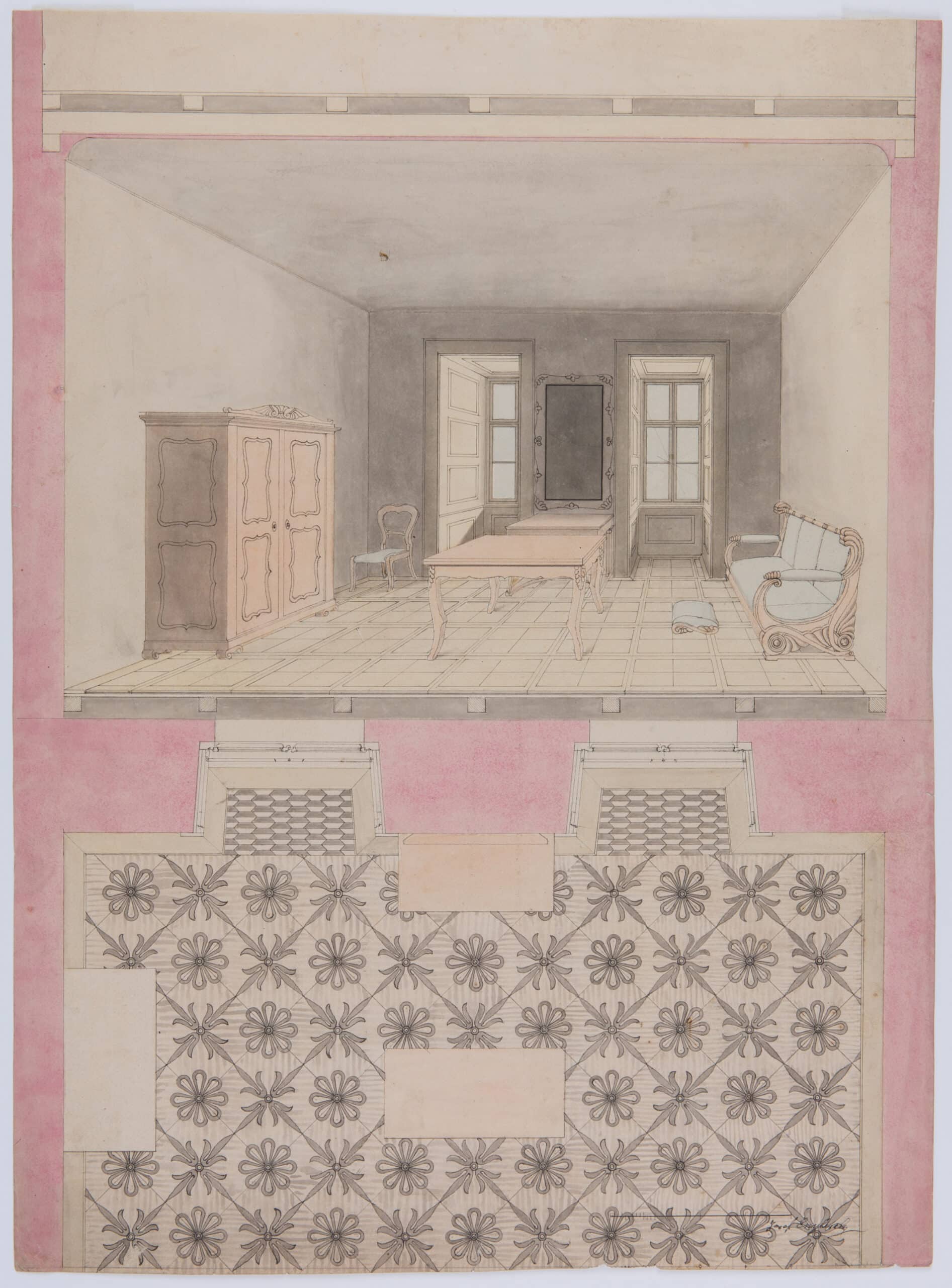

The collection of Viennese drawings is notable in that it spans a vibrant century of architectural design, when building played a key role in defining the character and ambitions of the capital of the Hapsburg Empire. Following the Congress of Vienna, which in 1815 redrew the map of post-Napoleonic Europe, the enforced political calm, the expansion of the middle classes, and a widespread mood of domestic introspection produced Biedermeier restraint in architecture, interior design, and furnishings. It is represented here by the drawing of an austere interior by Josef Englisch (DMC 1113).

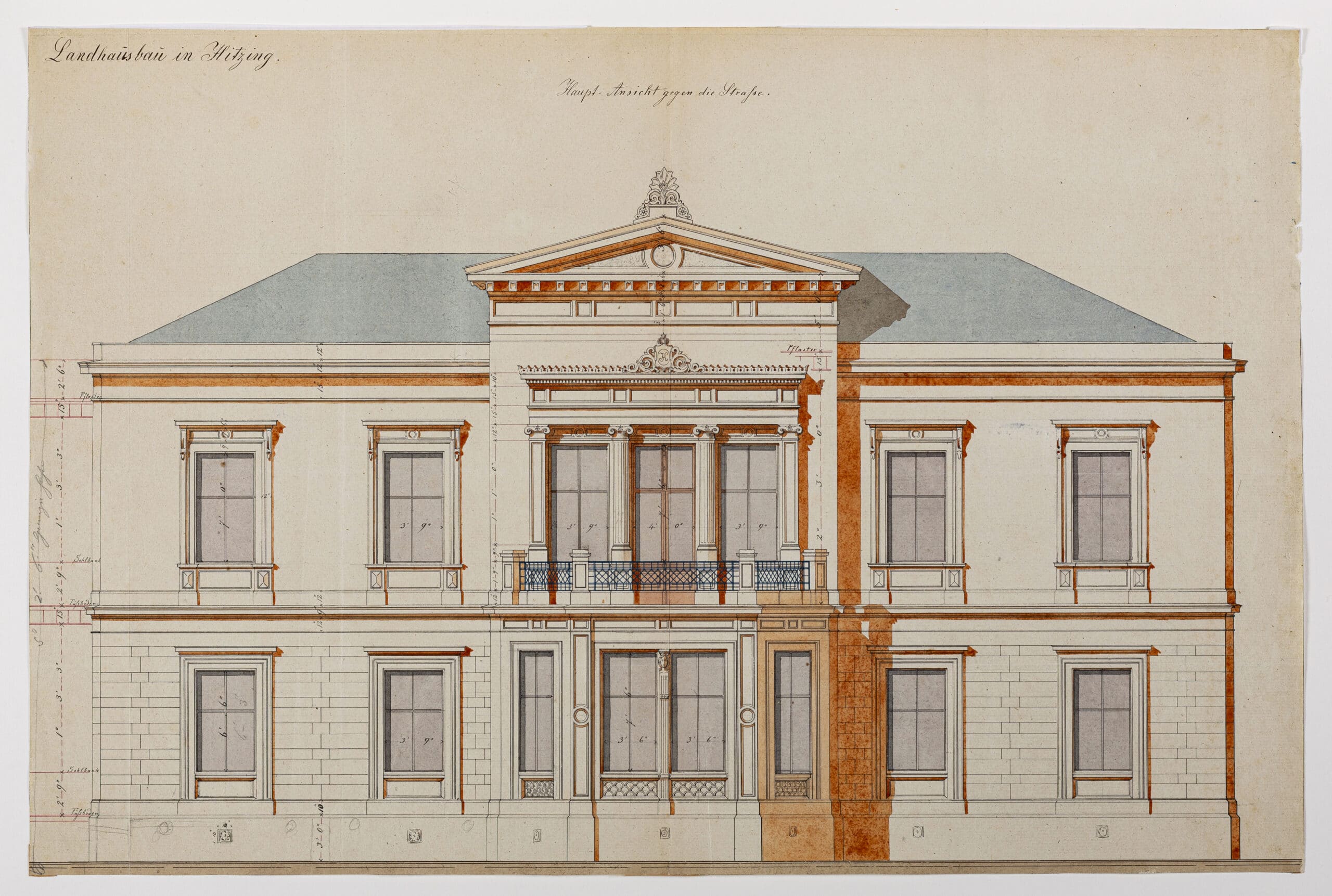

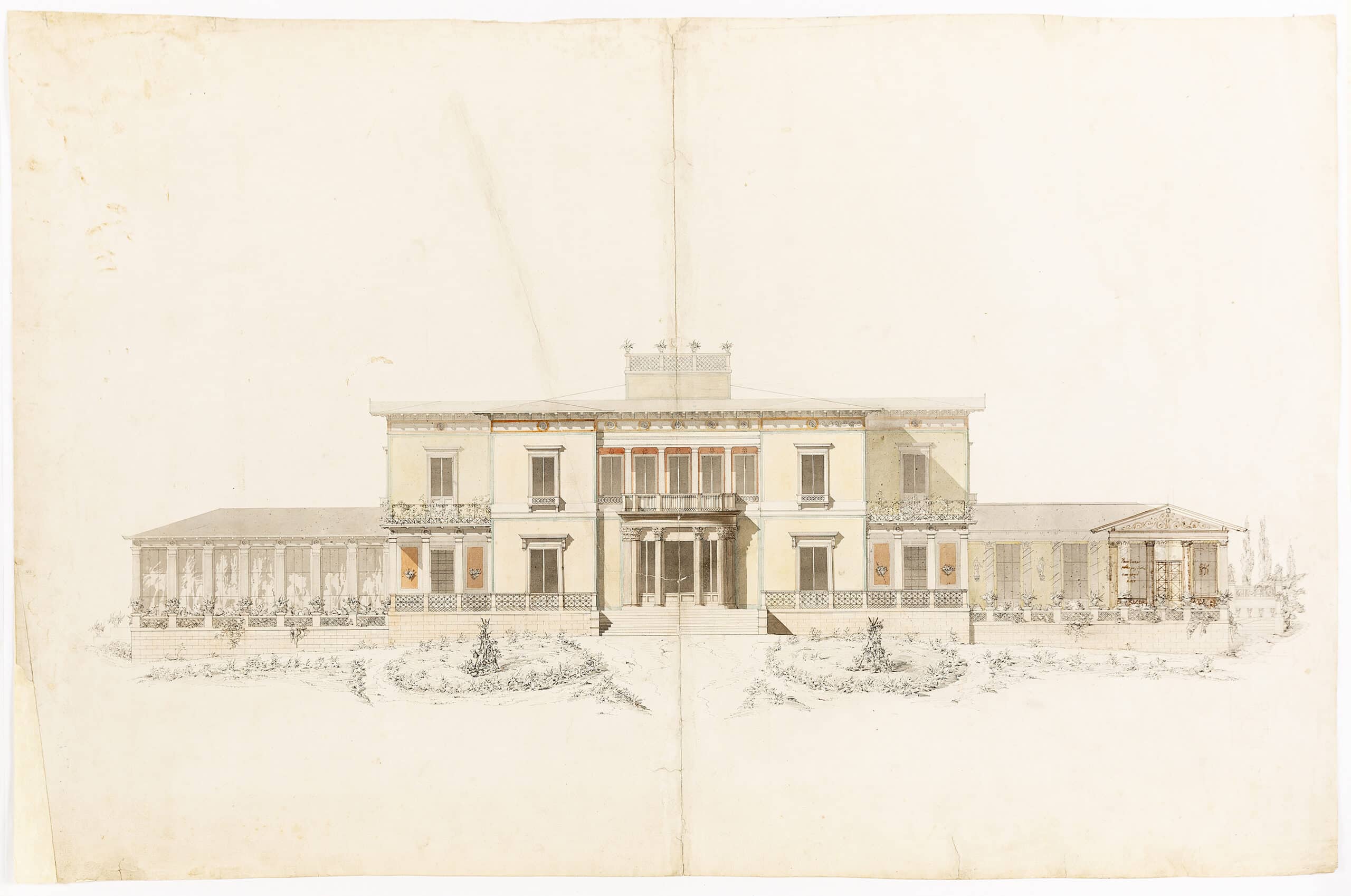

A comparable restraint can be seen in Johann von Ringe’s commission from Baron Karl Alexander von Hügel for a modest Italianate villa on the road from Hietzing to St. Veit (DMC1599). A vigorous traveler and hortologist, von Hügel spent six years in the 1830s traveling in the Middle East, Asia, and Australia. Returned to Vienna, he displayed his collection of exotic flowers and plants in the garden of his villa, which according to an early biographer ‘was celebrated for its floriculture and flower displays.’[1] A second villa from this period, designed by Franz Jacob Kreuter for Friedrich Gruber, is represented by ten drawings in the collection (DMC 2005.1—2005.9). Once again, the mood is Italianate, with loggias framed by Ionic columns, and Pompeiian paintings in the interior. Its owner, Friedrich Gruber, was a German cloth merchant and banker with strong Italian connections, who was called ‘Napoleone Commercianti’ in Genoa. His villa was completed in 1847, but his enjoyment of it was brief, as he died three years later in Palermo.

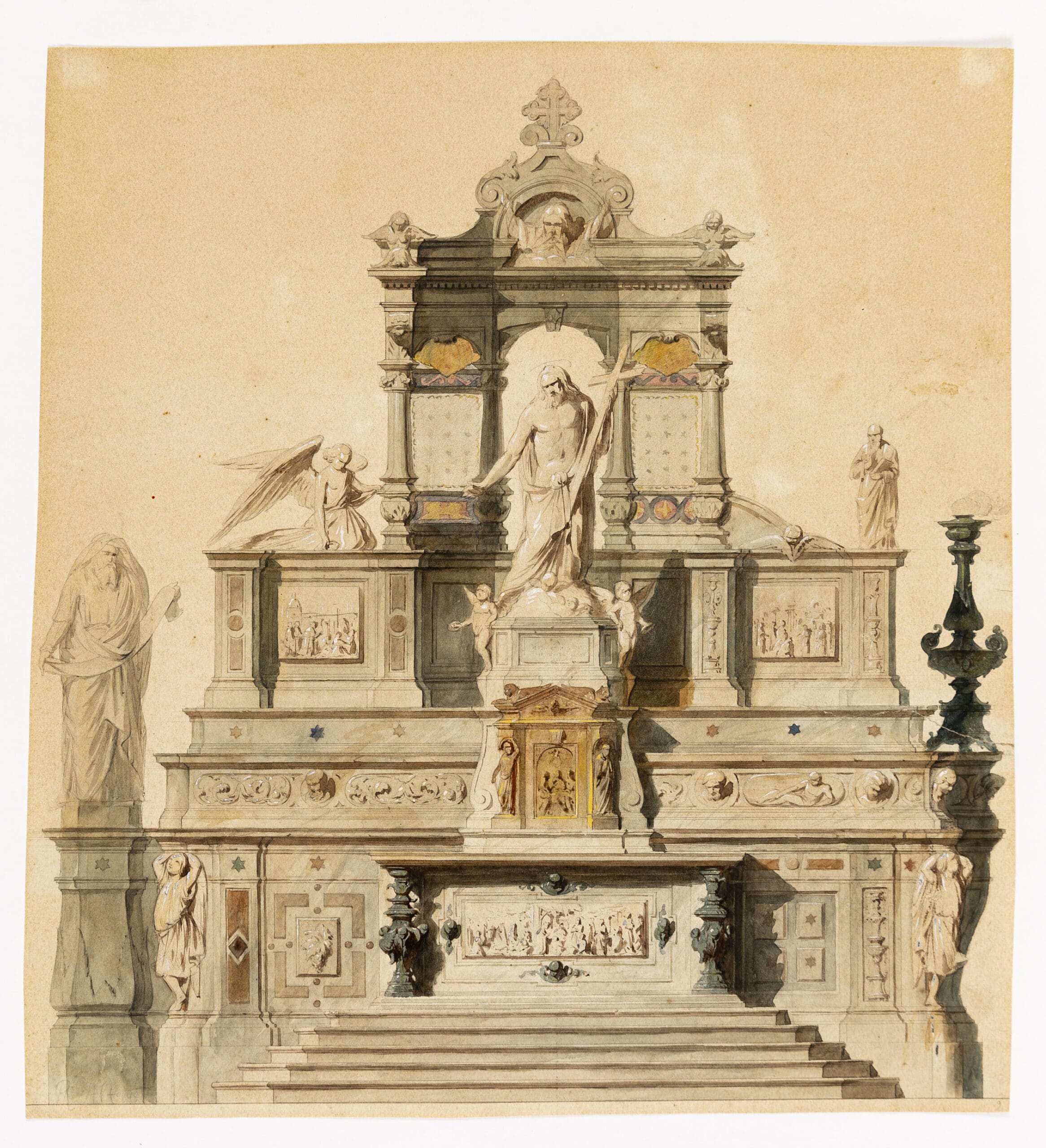

The calm and restraint of the Biedermeier era ended with another highly significant event in Viennese history, the uprising that began in March 1848. After years of state censorship and control from above, the streets of Vienna erupted, with the progressive ‘bourgeois subject’ joined by students and workers to demand a liberal constitution, which would free them from the absolutist rule of the Habsburg court and its agents, most notably the all-powerful Chancellor of State, Klemens von Metternich.[2] Vienna was an epicentre of this Europe-wide revolt, and over the succeeding decades, architecture gave voice to both liberal ambition and dreams of imperial grandeur. Rudolf von Alt’s altarpiece designs, dated to the revolutionary year of 1848 (DMC 2639), have a markedly transitional feeling, with a restrained, rectilinear structure, which echoed the Biedermeier, supporting neo-baroque decorative features.

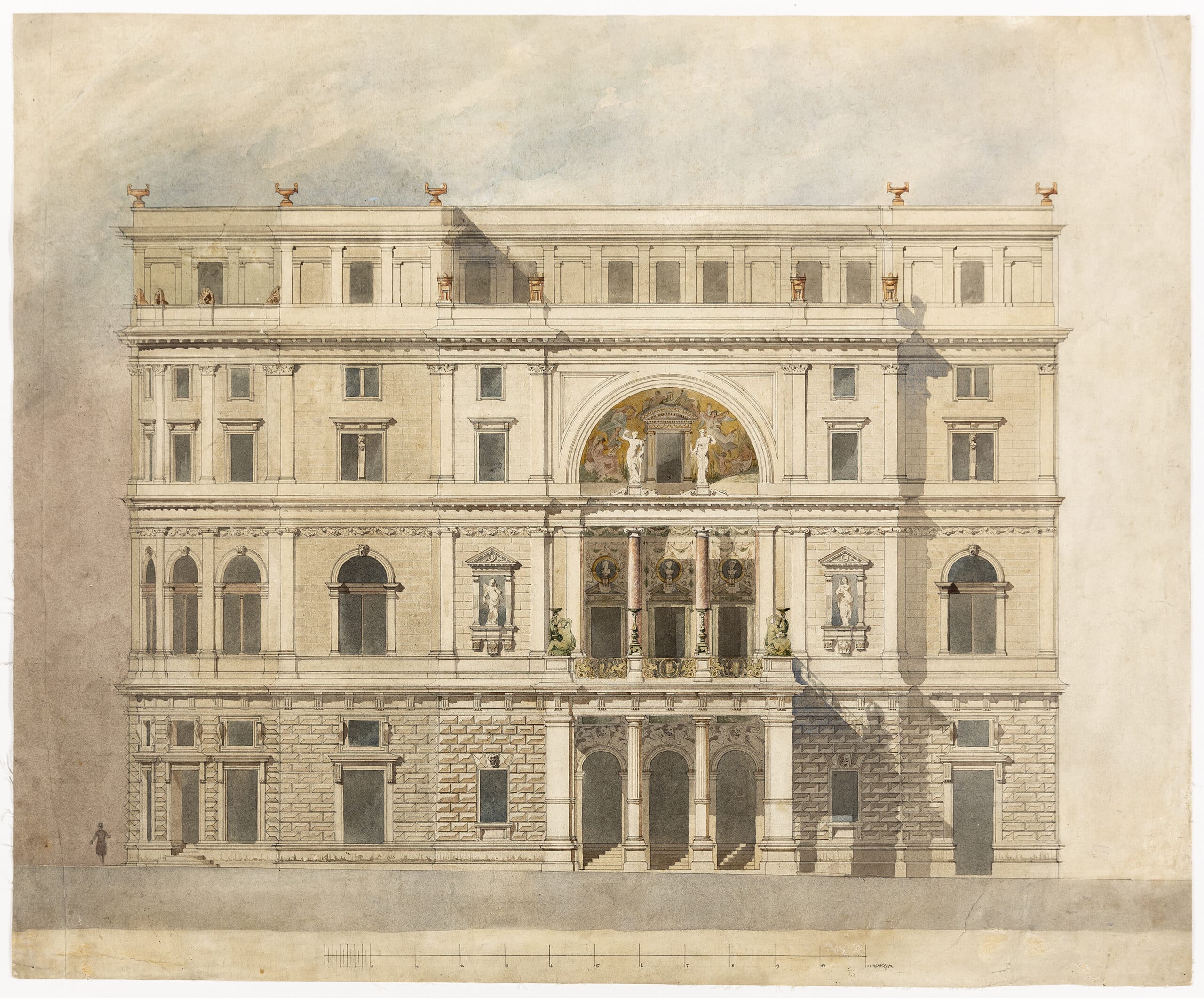

While the 1848 uprising prepared way for political revolution in Vienna and the emergence of a powerful bourgeoisie, the urban and architectural transformation and modernisation of the city began with the Kaiser’s decision of December 1857 to tear down the city walls that enclosed the historical inner city. Over the succeeding decades, the Ringstrasse was developed on the site of the former walls and the glacis, joining the historic city core to the expanding suburbs. With the Town Hall, Court Theatre, Parliament, Museums of Art and Natural Science, and the Opera, the grand new boulevard gave tangible form to the cultural and social ambitions of liberal Vienna in the later nineteenth century. It was a boom time for architects able to work on the grand scale, one of whom is represented in the collection: Heinrich von Ferstel. Ferstel’s initial claim to fame was his winning competition design for the neo-gothic Votivkirche at the Schottentor end of the Ringstrasse. This was conceived as a national monument marking the empire’s joy that the Kaiser had survived a knife attack in February 1853. Construction began in 1856, and the church was consecrated in 1879. By that time, Ferstel had become one of leading architects in Vienna and a master not only of the Gothic Revival but of the Italianate neo-Renaissance, which dominated the public buildings and the grand residences built along the Ringstrasse, many of which were the work of Ferstel. The drawing described as ‘Design for a public building’ (DMC 1962) may relate to his design for the University of Vienna, completed in 1884, a year after the architect’s death.

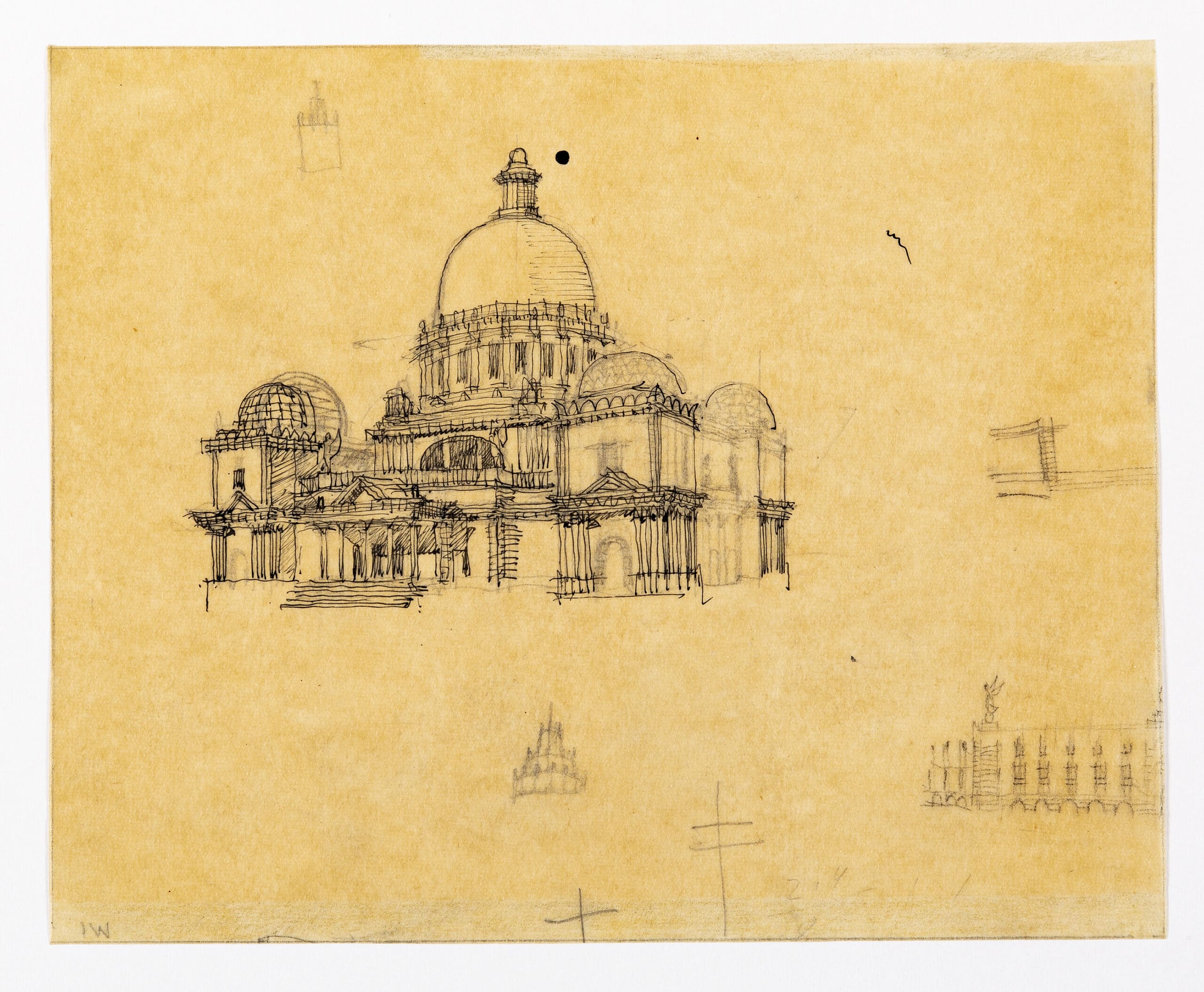

In 1867 Ferstel submitted an unsuccessful design for the Berlin Cathedral competition, as did his compatriot, Otto Wagner (DMC 2063). While Wagner’s scheme referred to Renaissance precedent, his lasting contribution to the architectural discourse in late nineteenth-century Vienna was his rejection of the mid-century historicism that had been favoured for the city’s public buildings: Doric for the Parliament; Gothic Revival for the Town Hall, Neo-Renaissance for the University and Opera. This challenge found expression in Wagner’s own buildings, most famously the Post Office Savings Bank, and in his teaching. His argument for an architecture aligned with the demands of the modern, industrial age was clearly stated in his 1894 inaugural lecture and in his radical teaching programme at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. While Wagner himself is only sparsely present in the Drawing Matter collection, his students at the celebrated Wagnerschule, are well represented.

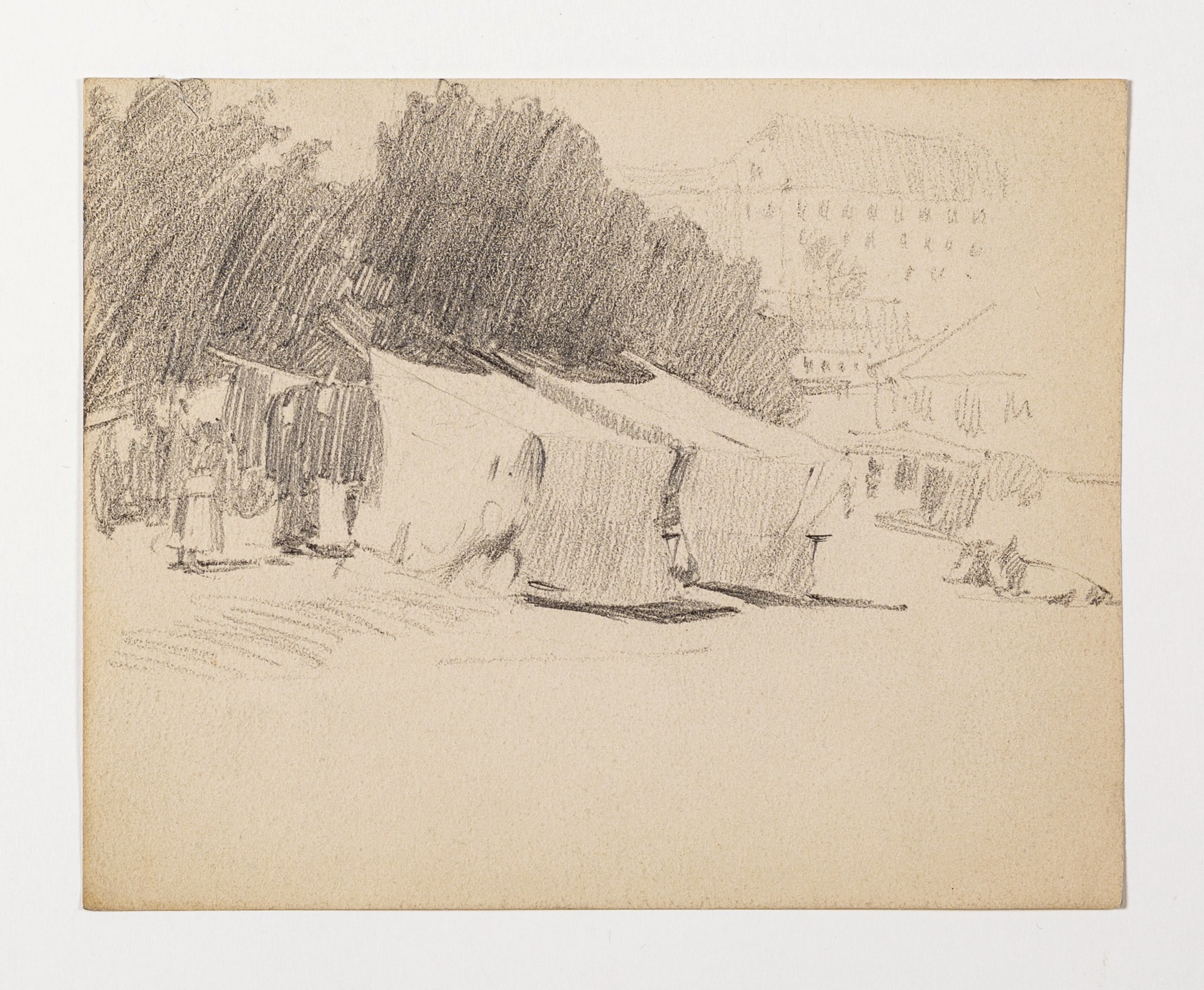

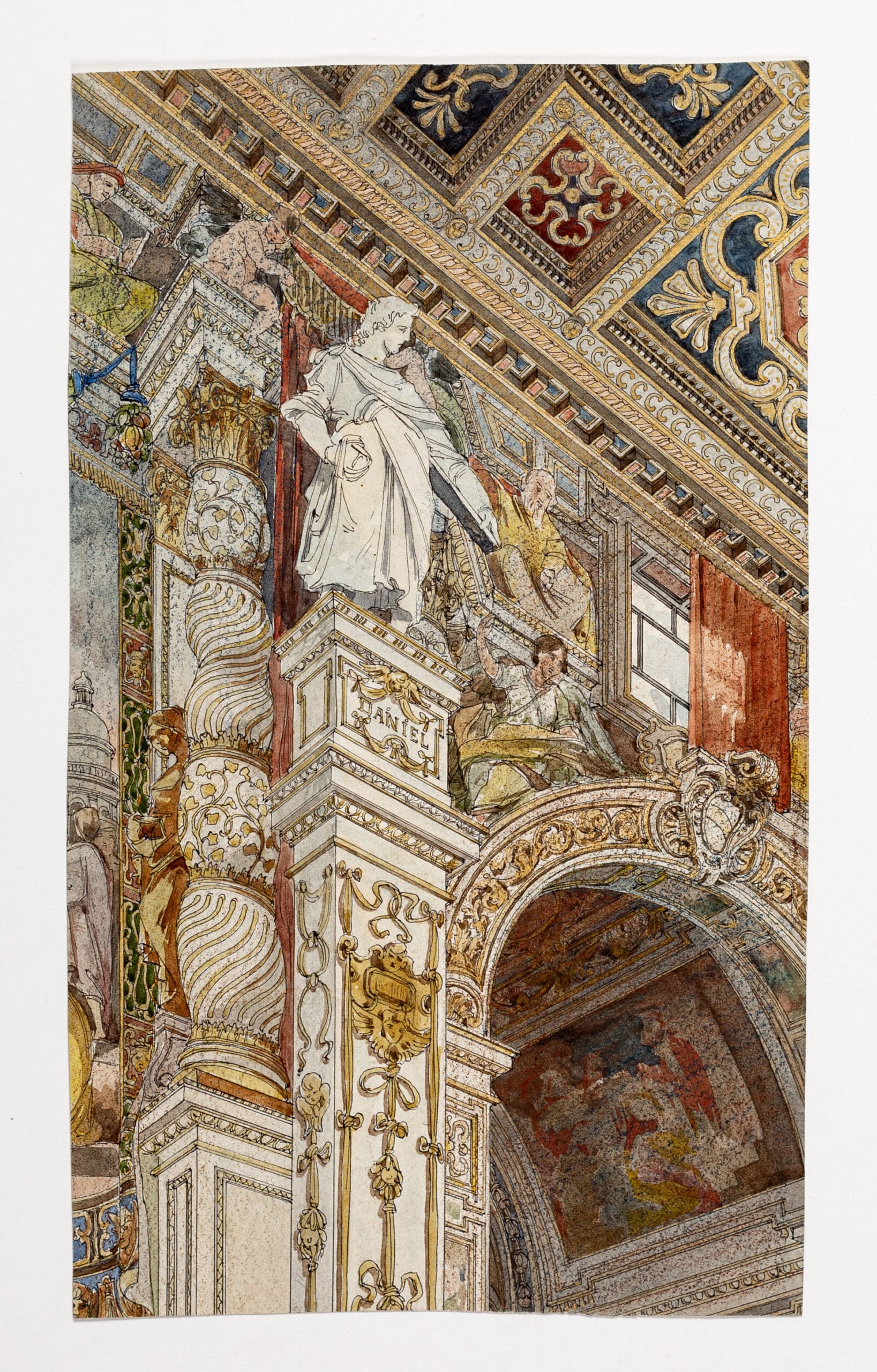

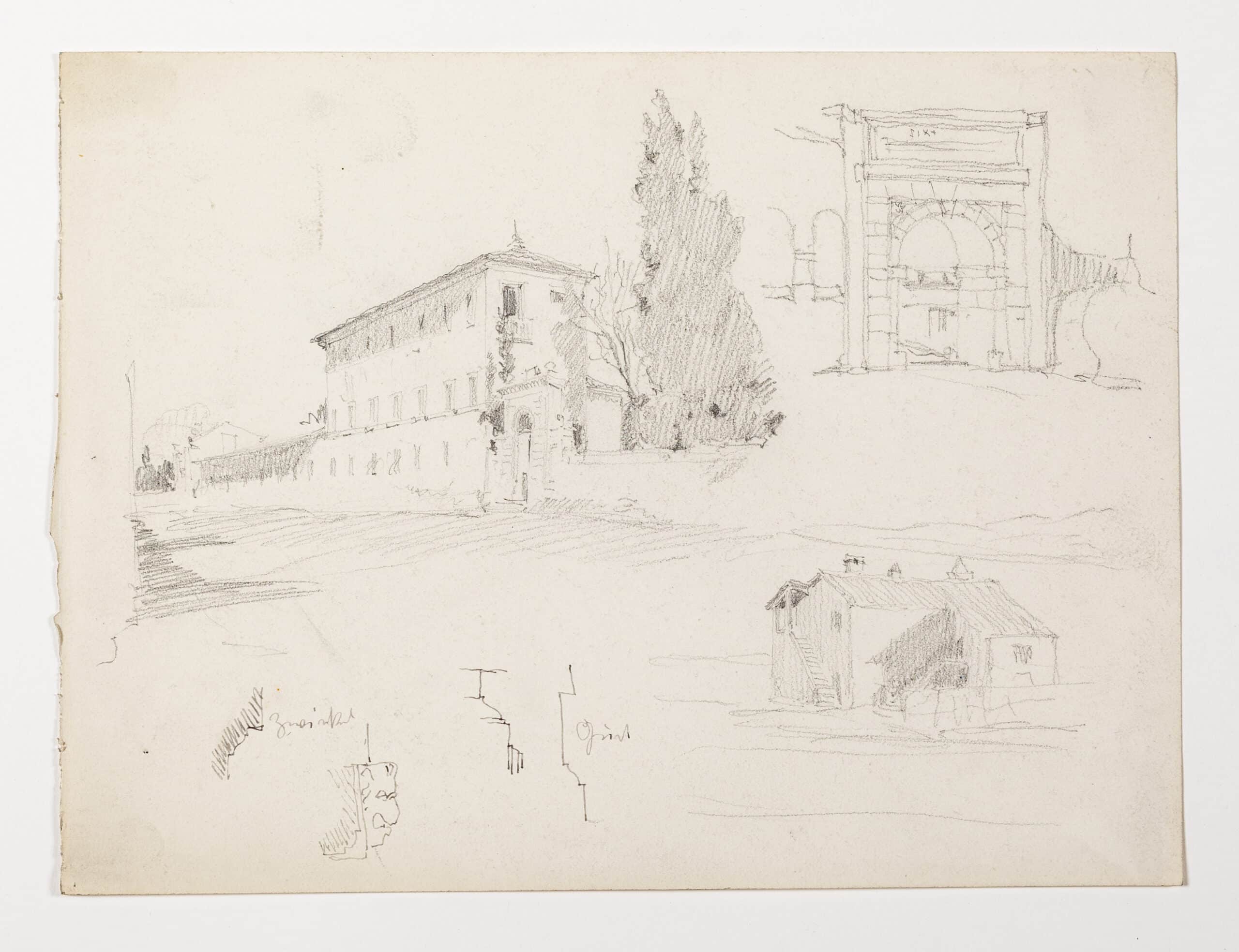

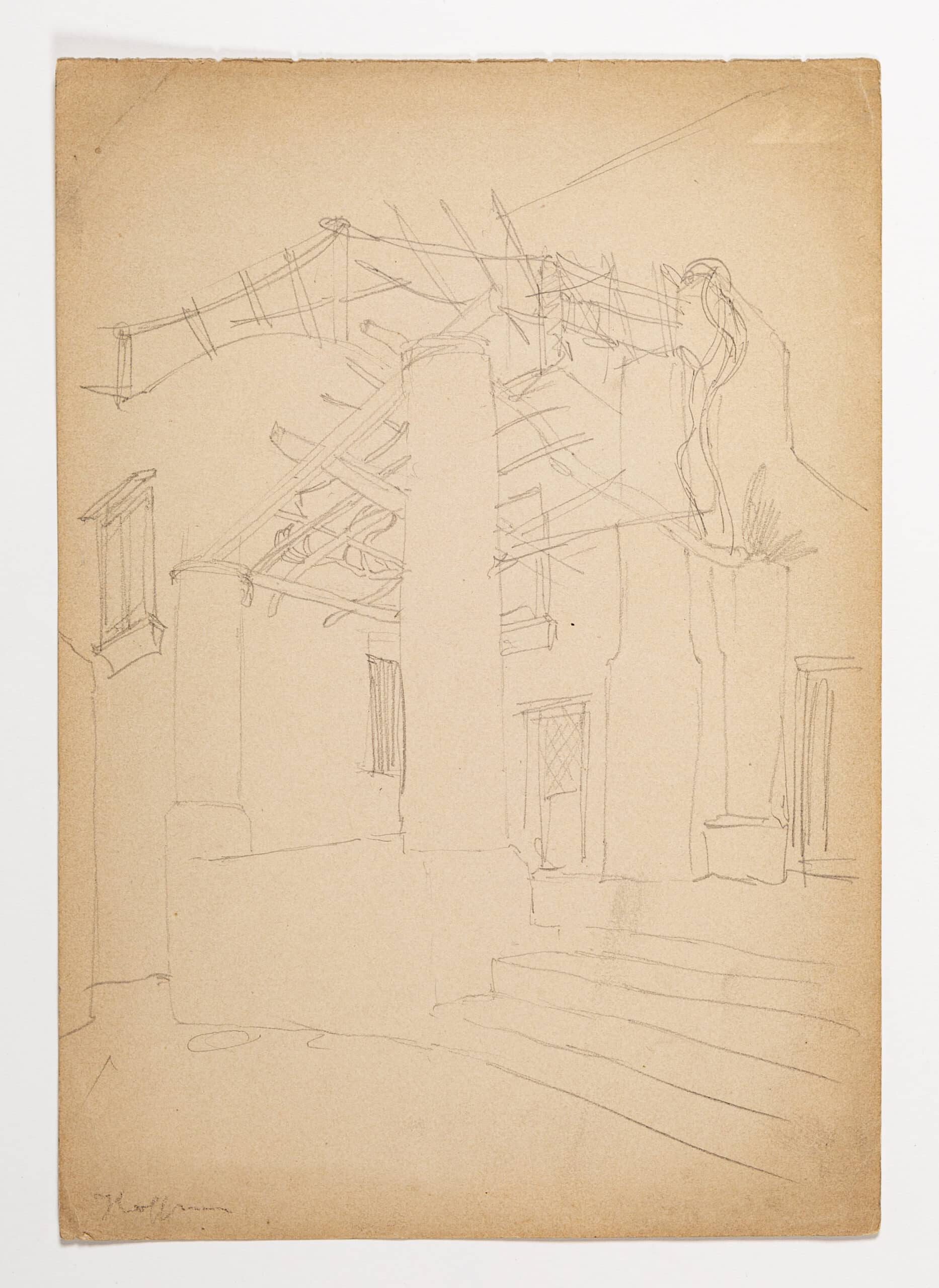

Joseph Hoffmann matriculated at the Academy in October 1892, initially in the class of Professor Karl von Hasenauer, a very distinguished architect but, according to Hoffmann, a singularly dull teacher. Hasenauer died, however, in January 1894 and the vacant professorial chair was filled by Otto Wagner, who brought a fresh impetus to the school. In their first year, Wagner’s students—all of whom already had a first diploma in architecture—were asked to design a Viennese apartment house. The second year saw them working on a public building, while for the third year Wagner urged his students to pursue ‘a task that will never confront them in real life, a task whose solution will served to fan into bright flames the divine spark of fantasy that should be glowing within them.’[3] For Hoffmann, this meant a vast domed and colonnaded project for a Palace of the Nations, submitted to the Academy in 1895, which won him a travel stipendium to go to Italy. Ever sceptical about the uncritical imitation of historical models, Wagner urged Hoffmann ‘Don’t look so long at the old trash, rather go to Paris and look around there.’[4] But as the 200 or so sketches made by Hoffmann confirm, he was fascinated by the wealth and diversity of Italian building.[5] In addition to topographical sketches from Italian cities including Verona (DMC 3850.7), Florence (DMC 3850.13), Rome (DMC 3850.21), and Syracuse (DMC 3850.26), Hoffmann’s drawings reflect the breadth and diversity of his responses to Italy. These range from a highly skilled rendering of the interior of a museum, possibly the Vatican Museum (DMC 3850.18), to a very simple sketch of a vase set on a pedestal in a Palermo park.

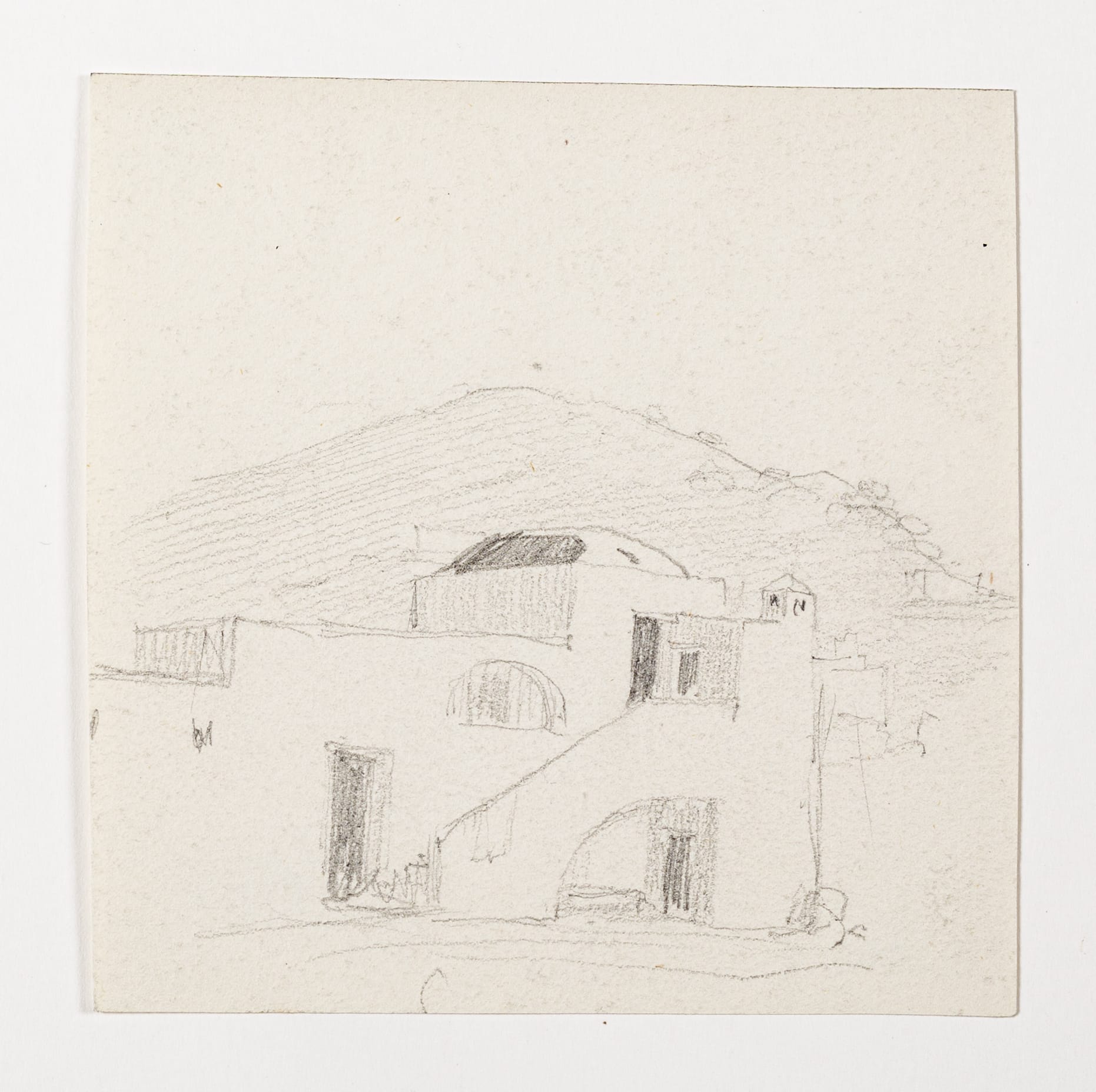

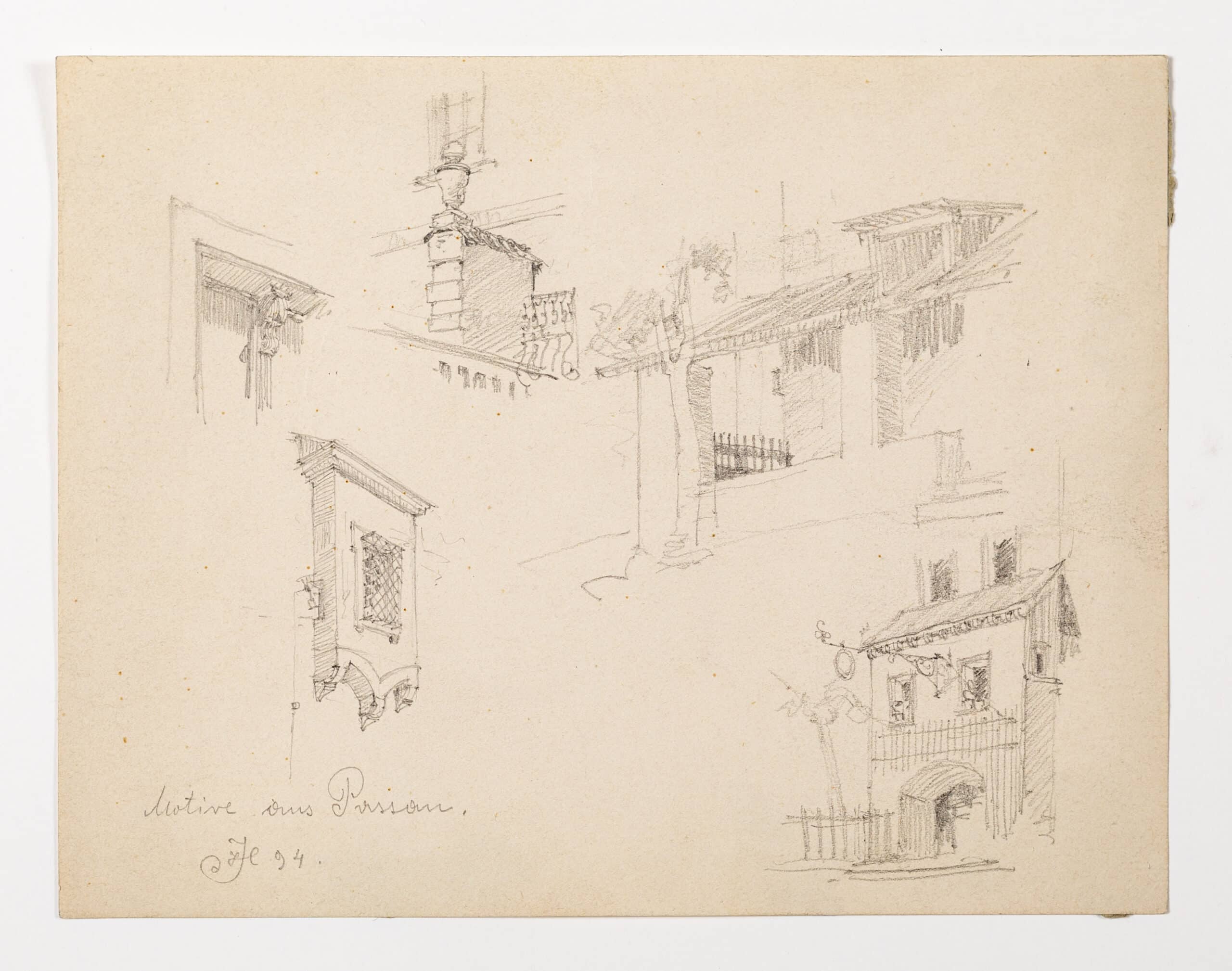

Hoffmann’s Italian drawings are symptomatic of the search for a new authenticity, grounded not in the direct imitation of historical models, but in an understanding of history as an inspiration for new design thinking. This search had both temporal and spatial dimensions. Going back in time, Hoffmann’s sketch of Roman structures on the Via Appia outside Rome is composed of reduced, Euclidean geometries fronted by an ancient cypress tree (DMC 3850.32). A similar simplicity was also found in the vernacular building of Italy. Capri was a great favourite for Hoffmann, and prompted him to pen a very short text in 1897 on the island’s buildings, which recalled that in addition to the glorious location and friendly locals, he was particularly charmed by ‘the still almost entirely pure, vernacular manner of building.’[6] The Drawing Matter collection has several sketches of simple, undecorated structures on whose facades one can almost feel the warmth of the southern sun (DMC 3850.8, 3850.11, 3850.34, 3850.45). Following in the influential footsteps of Ruskin and Morris, further strengthened by the upsurge of cultural nationalism within the Hapsburg Empire, the local vernacular of Northern Europe also emerged in the late nineteenth century as inspiration for the architectural avant-garde. Sketches by Hoffmann from the German town of Passau, on the upper reaches of the Danube, make this point (DMC 3850.1), as does the drawing of a simple cottage with a gambrel roof (DMC 2047), which is strongly reminiscent of Hoffmann’s design for the Bergerhöhe, an old farmhouse near Hohenburg in Lower Austria, which Hoffmann converted in 1899 into a rural retreat for the industrialist Paul Wittgenstein. While the simple external elevations fully respected the rural traditions, the interior was a powerful statement of contemporary Secessionist fashion, with the architect responsible for every design detail. This, in miniature, was the avant-garde paradigm of innocence and innovation: the innocence of a bygone, pre-industrial world, combined with the technologies and fashion consciousness of the modern era.

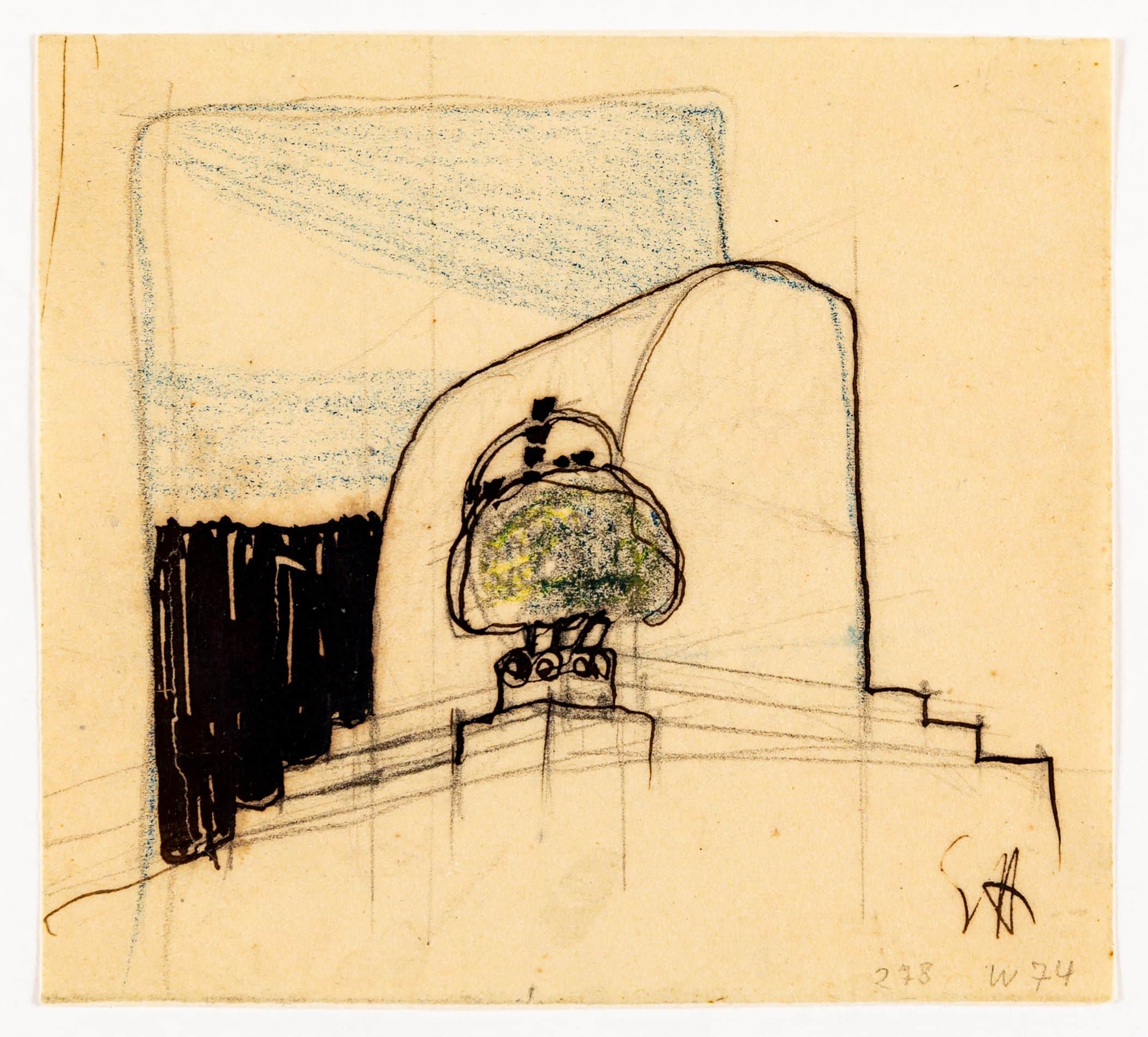

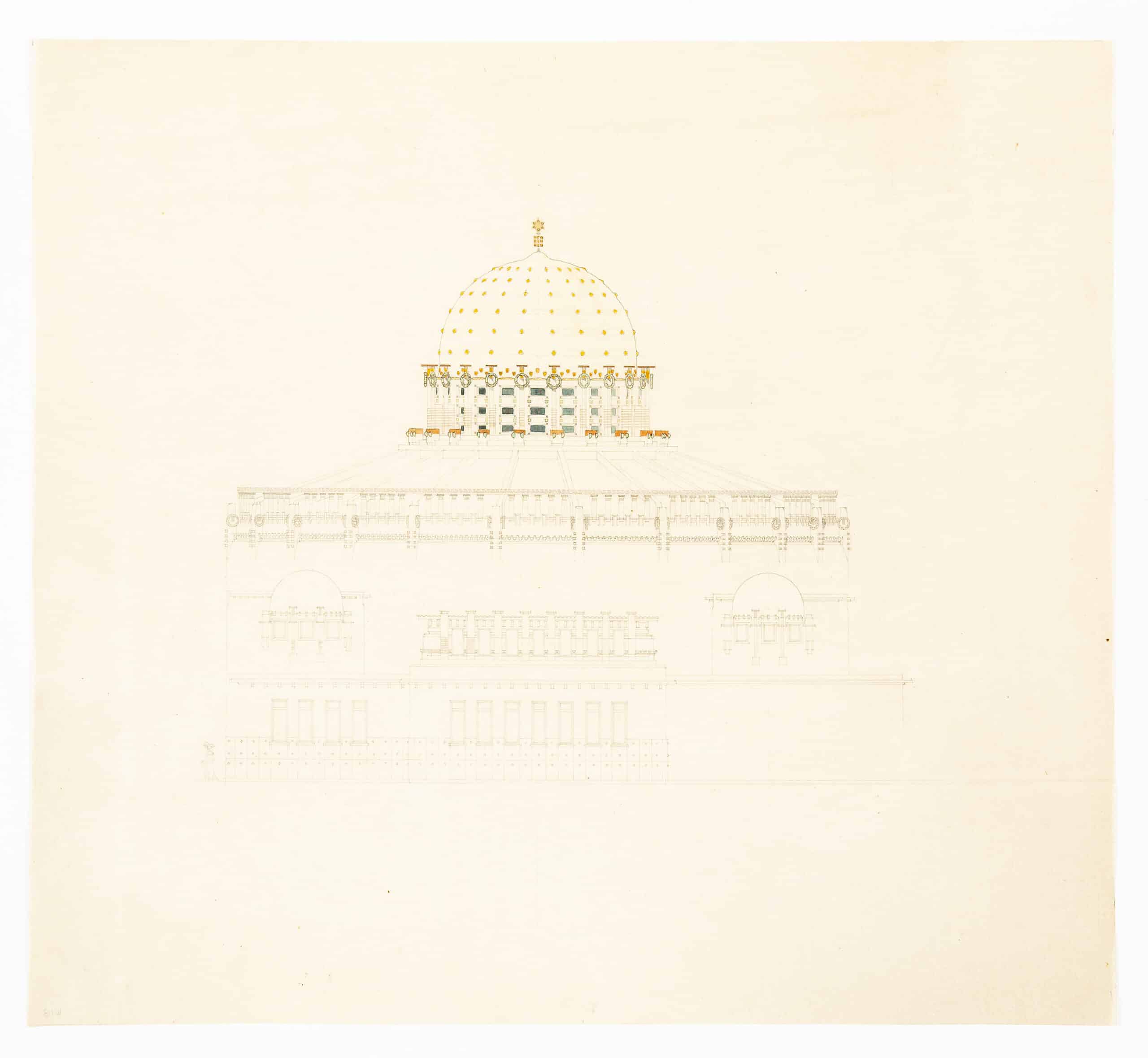

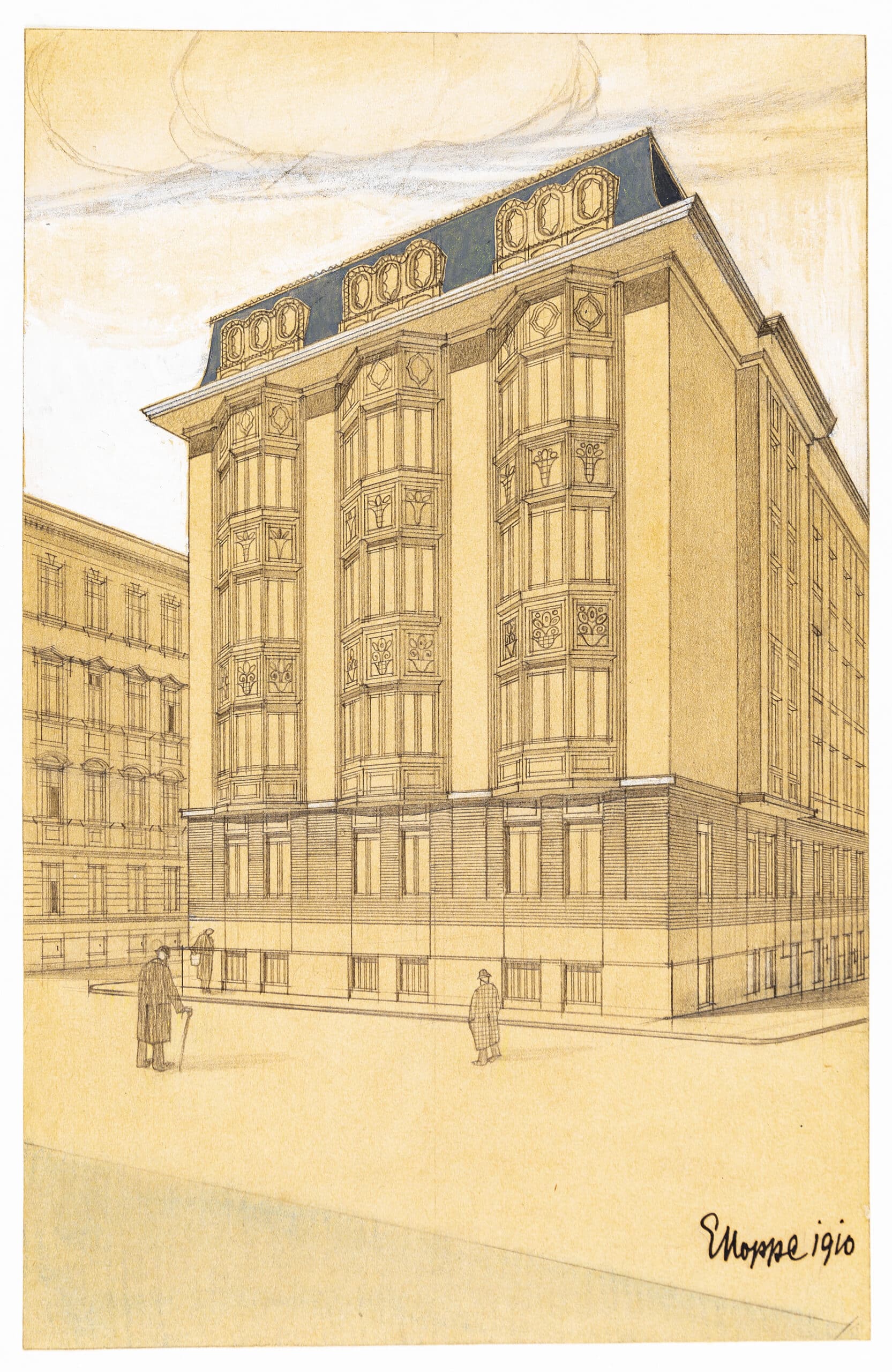

This potent fusion of the archetypical and the modern characterised the products of the Wagnerschule until its demise in 1912. Emil Hoppe and Otto Schönthal joined Wagner’s class in 1898, and followed the pedagogical programme pioneered by Hoffmann. Schönthal’s third-year project was for a cemetery church, developed an unsuccessful competition entry from 1900 for a new church at the Central Cemetery, which according to the Viennese wits was ‘half the size of Zurich, but twice as much fun.’ Schönthal described the intended experience of his church in poetic terms: ‘Moving through a golden portal—the sacrament of baptism—the human throng forms a frieze that runs in a band around the church, passing Guardian Angels who deliver the seven sacraments. […] Stretching mightily above the portal is the cross of the Saviour, in gold and precious stones. The nearer the believer approaches to the sanctuary, the more massively it seems to tower above the iron dome. Angels float around the Son of God to kiss the holy wounds.’[7] Flanked by sculptural cypress trees, Schönthal’s domed church and its sculptural decoration feature in several of the drawings in the collection (DMC 1913-1918; 2179.1-.9).

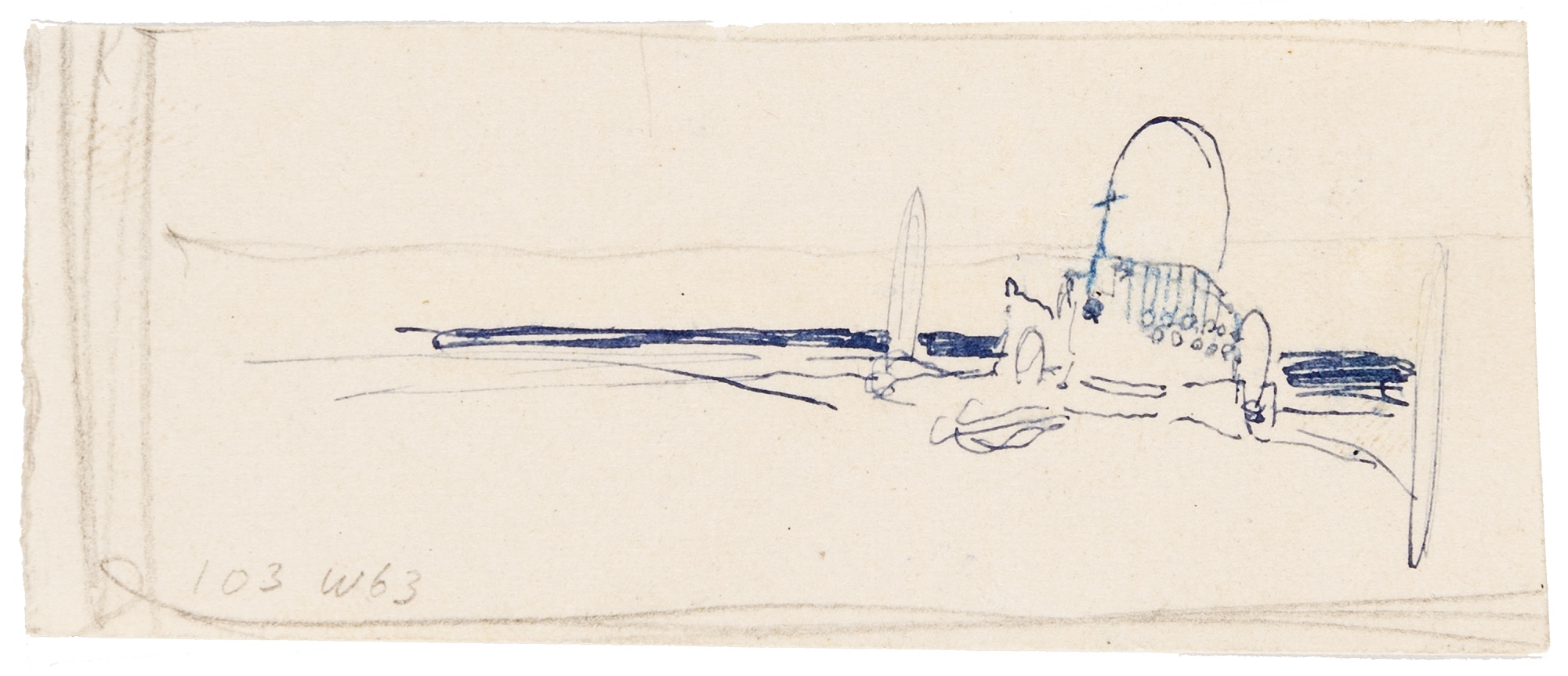

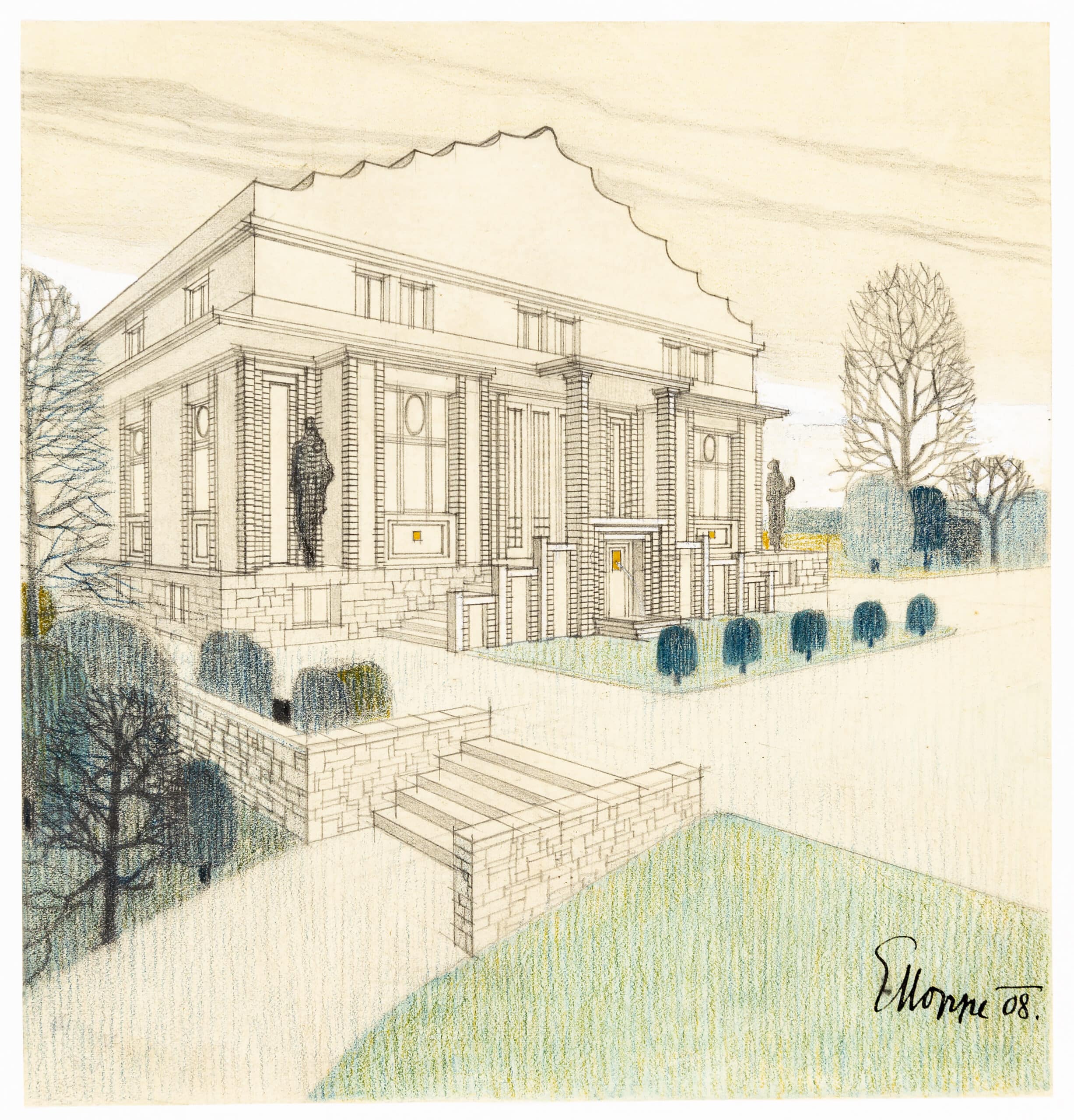

Like Hoffmann and Schönthal, Emil Hoppe also made a study trip to Italy, which inspired him to invent very simple, monumental edifices, drawn with low perspectives, stepped approaches, and some sort of sculptural climax: there is one example in the collection (DMC 1921). Their impact on the Italian Futurist architect, Antonio Sant’Elia has often been remarked on, and Hoppe’s drawings can justifiably be seen as a potent hinge between imperial Roman monumentality and the metropolitan architecture of the future.[8] Returned to Vienna, Hoppe scaled down these monumental aspirations as the designer of several tombs, both built and imagined (DMC 1929-1935, 1938, 1939, 1941).

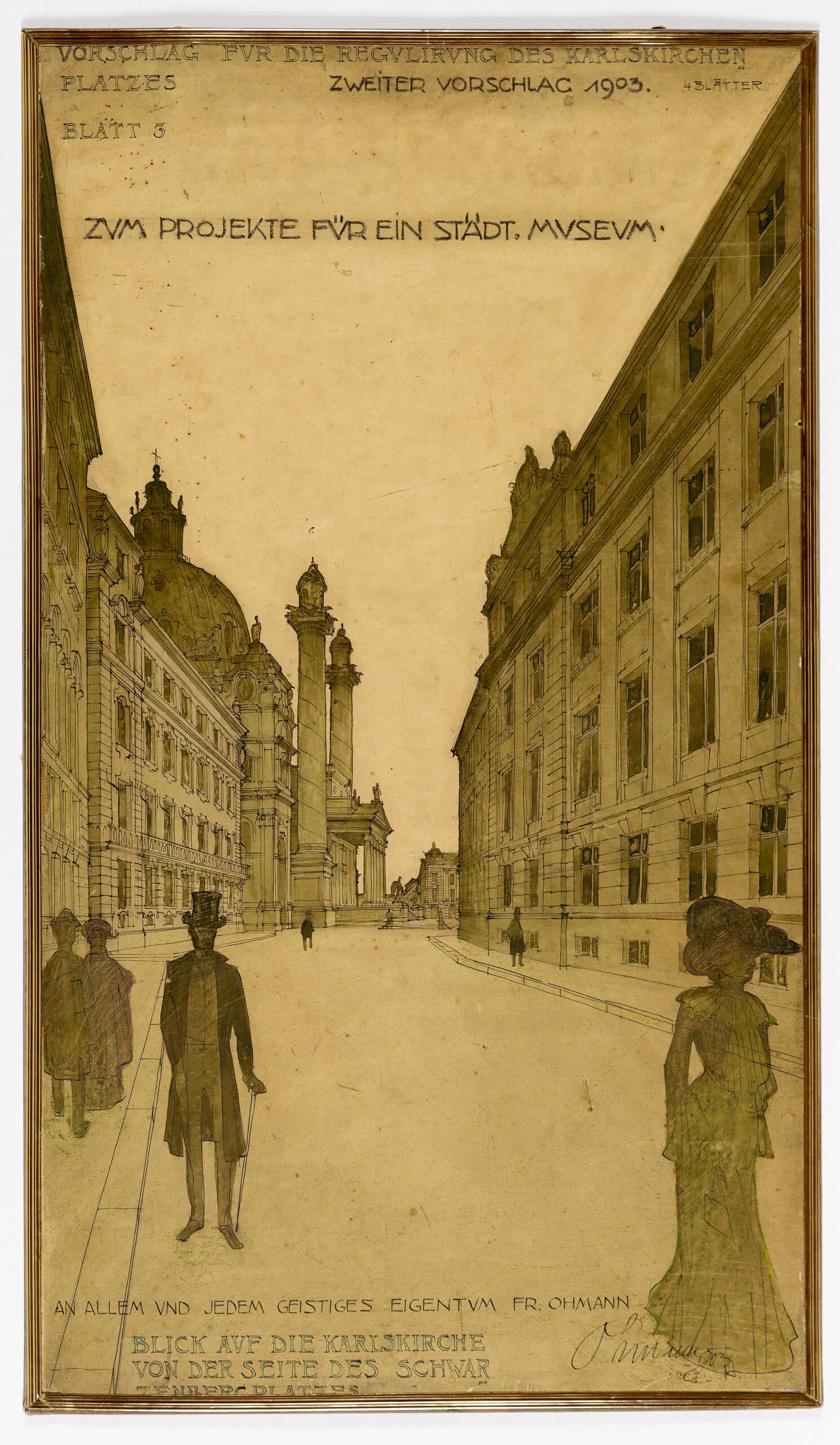

Wagner invited his most talented students to work as assistants in his private studio, which was directly beside the student drawing office. Drawing was the key skill. As Wagner’s first biographer noted: ‘He is not only a truly excellent draughtsman himself but has also evaluated and chosen his students and studio assistants according to their abilities in this respect.’[9] As an assistant, Hoffmann worked on Wagner’s great bridge that took the city railway over the River Wien at Gumpendorferstrasse. Similarly, and doubtless encouraged by Schönthal’s work on domed churches, Wagner employed him, together with his fellow Wagnerschule student Marcel Kammerer, as site architects on the Steinhof Church, built between 1903 and 1907. The insistence on drawing abilities was not unique, however, to Wagner and his pupils: it was symptomatic of Viennese architectural culture in general at the turn of the century. The drawing in the collection of Friedrich Ohmann’s project for the Stadtmuseum—with the Karlskirche in the background and elegant Viennese sauntering along the street in the foreground—is a typical example (DMC 2048).

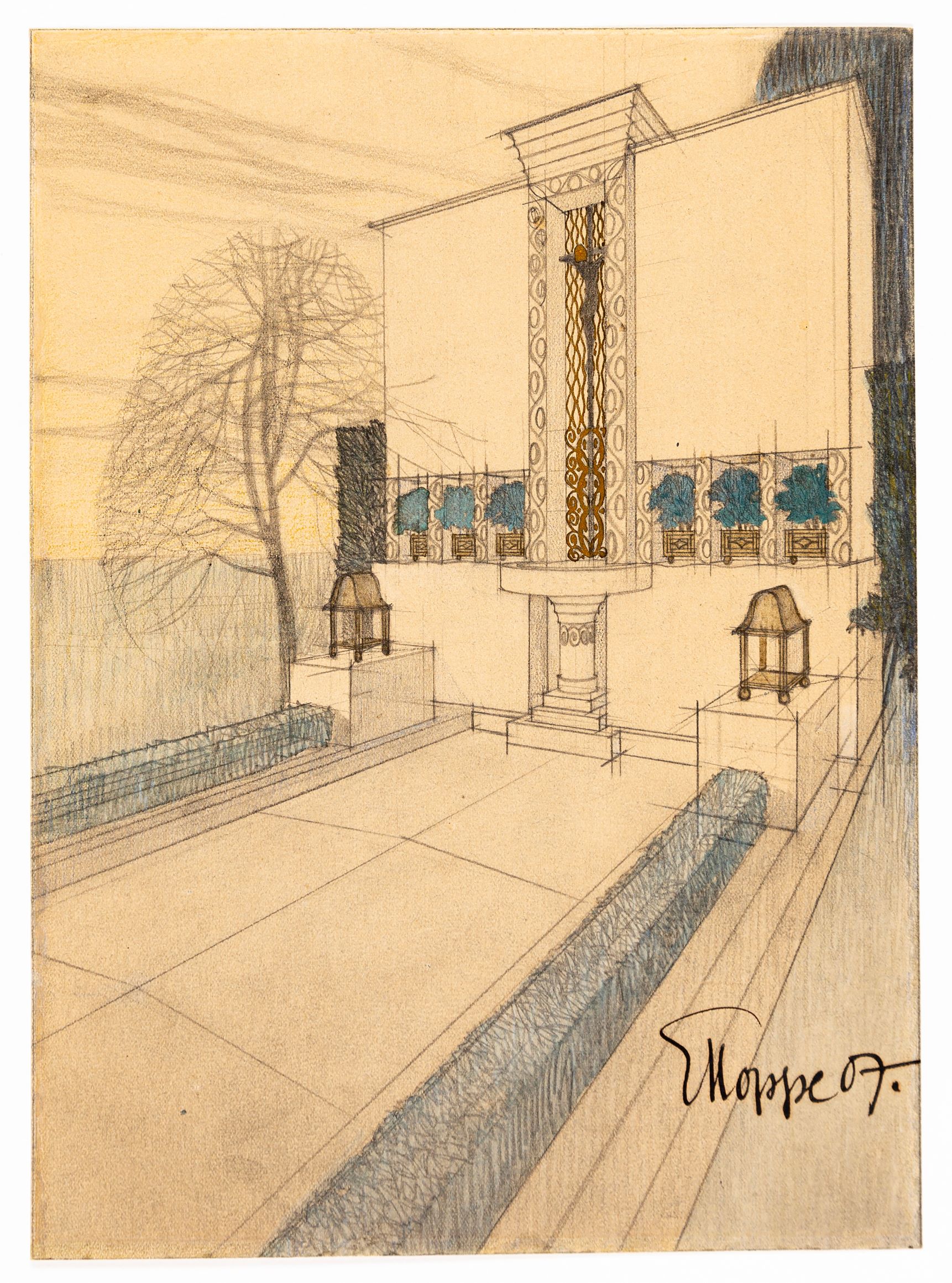

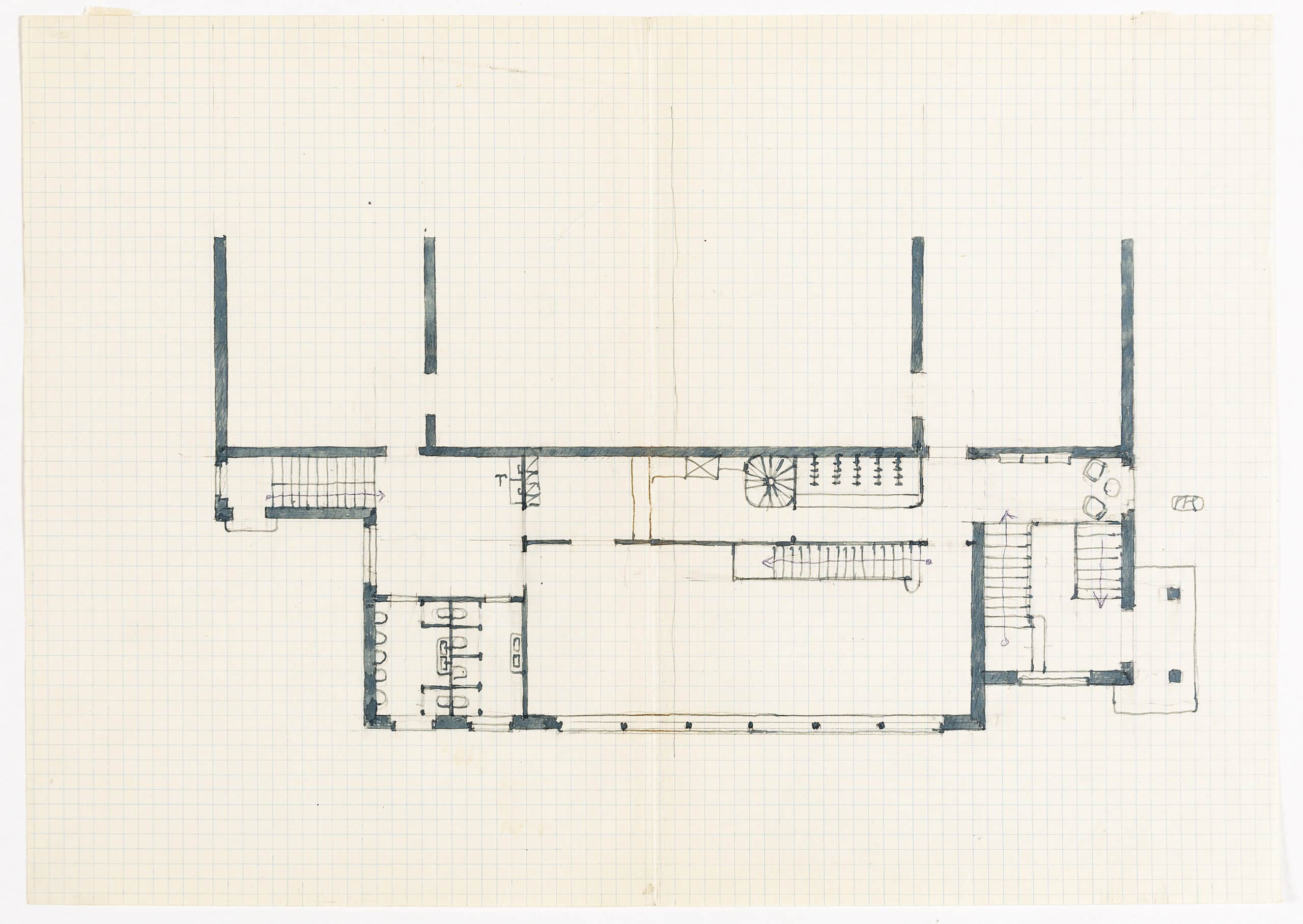

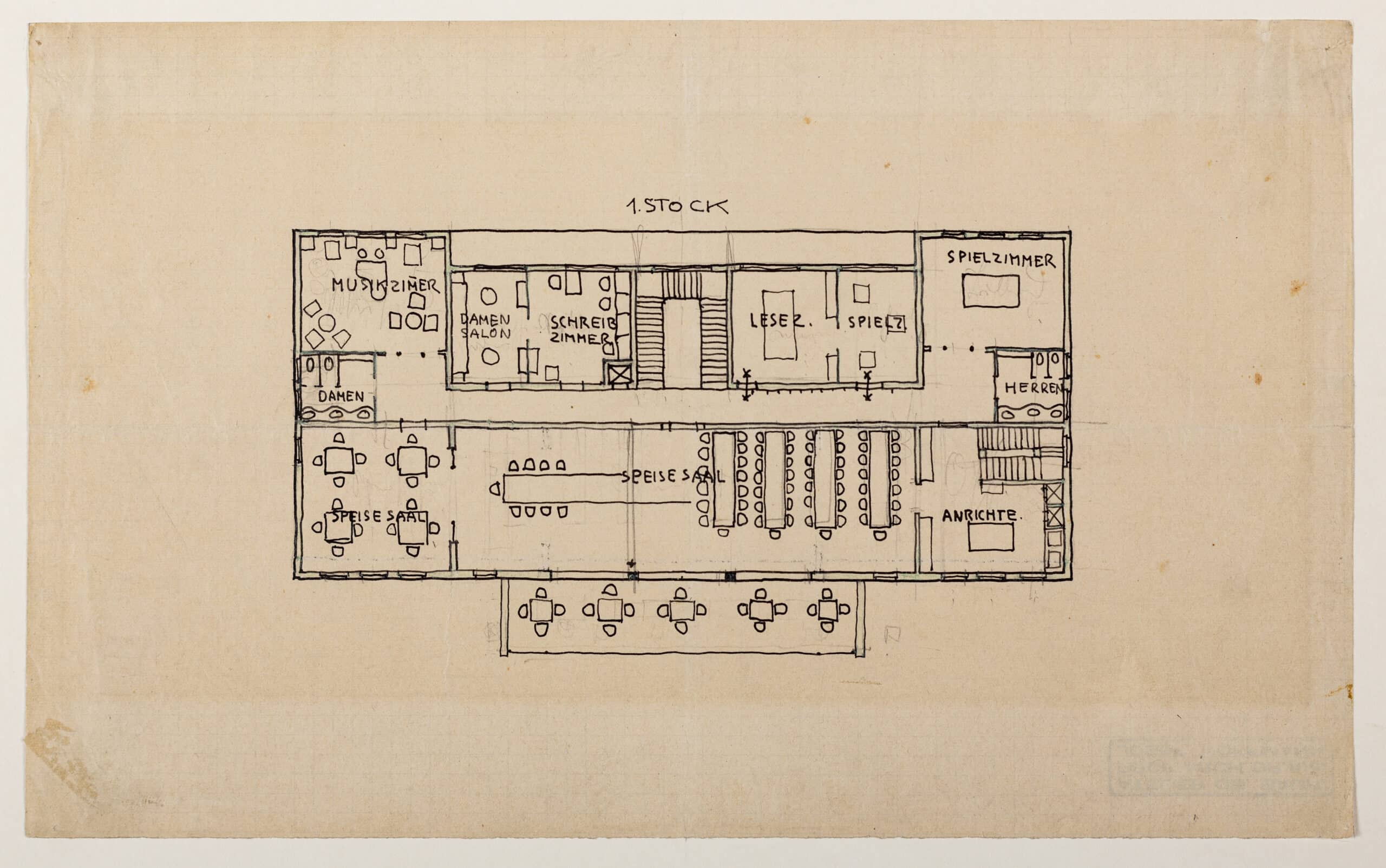

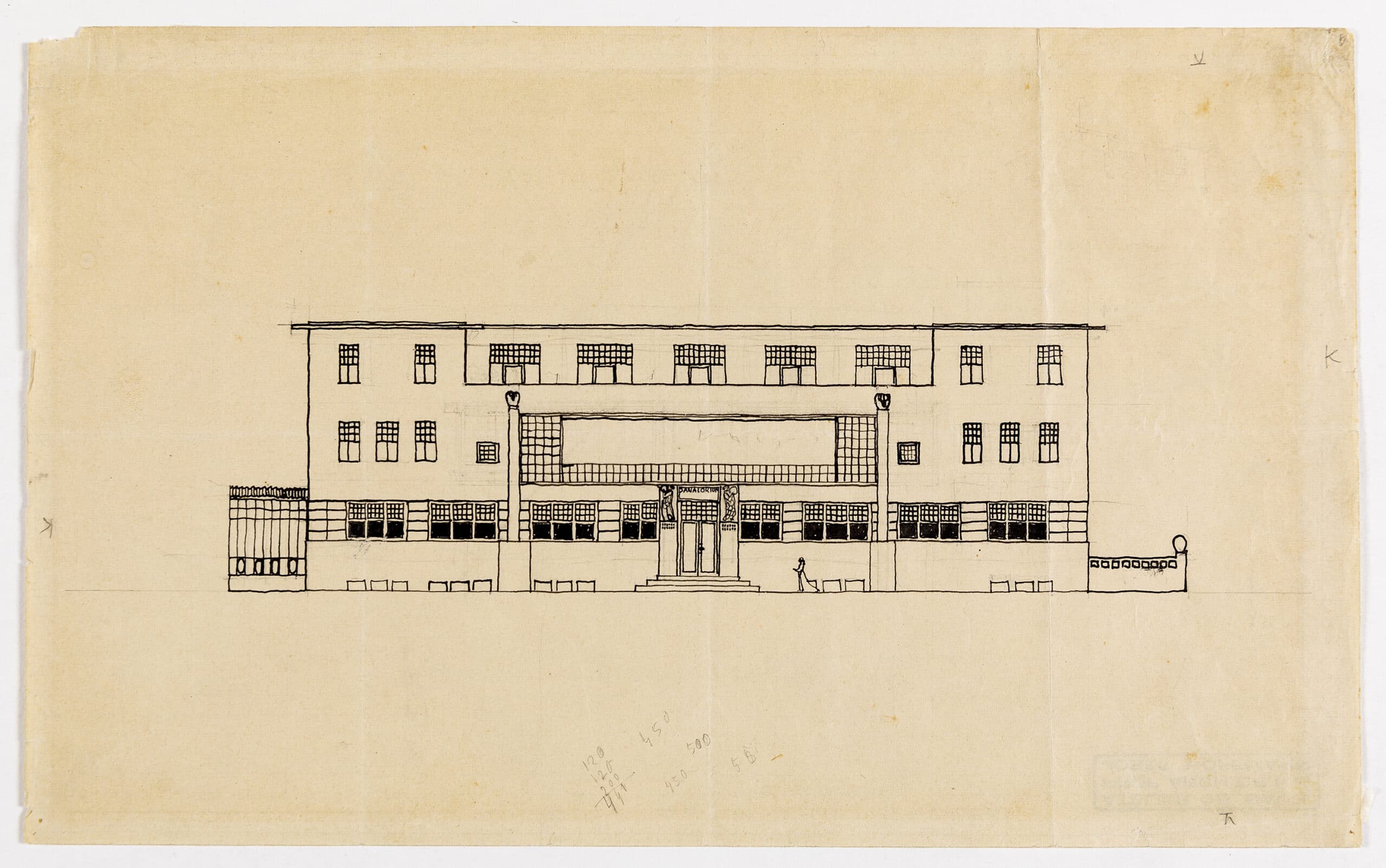

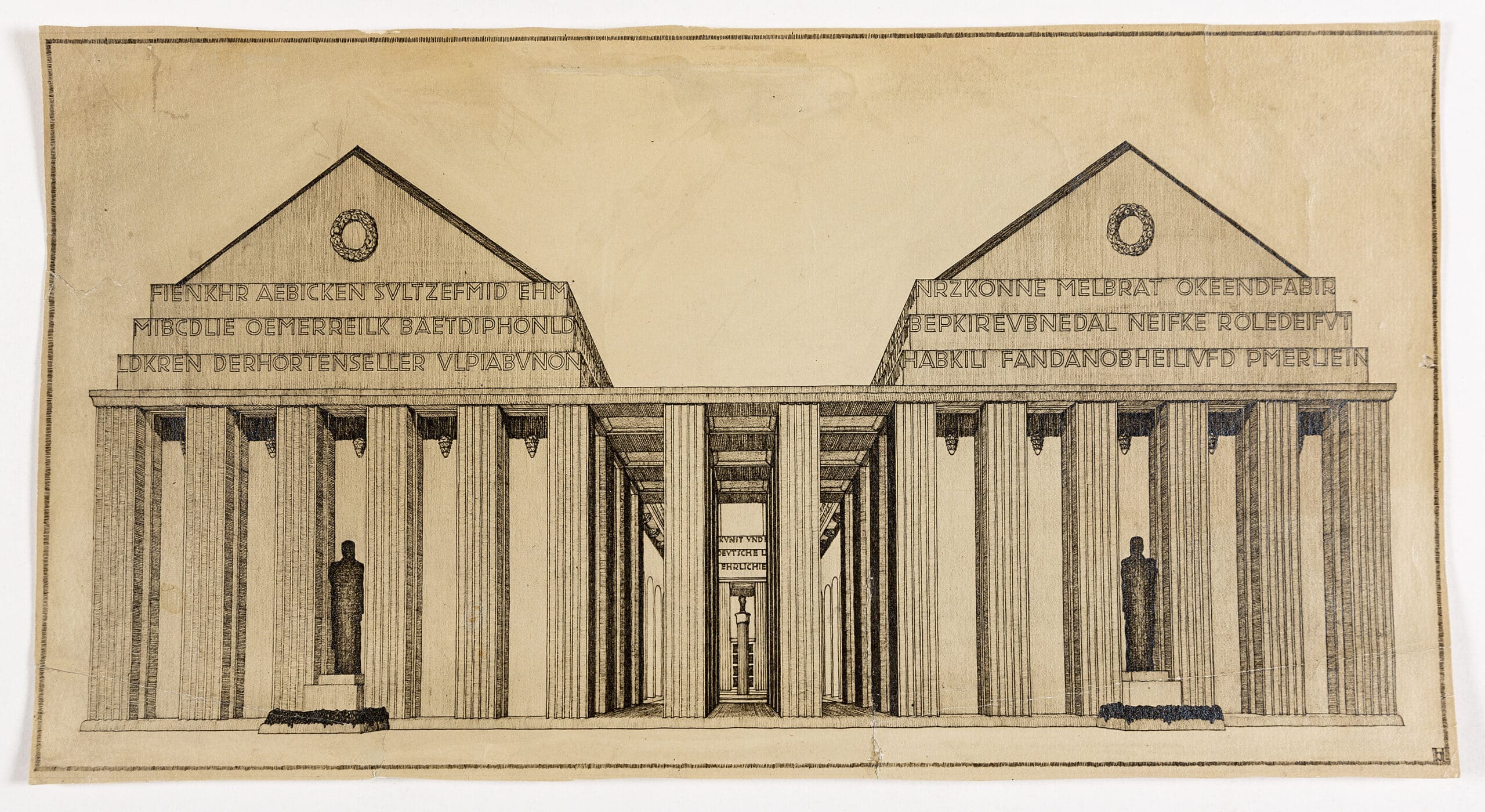

Fruitful careers beckoned, however, beyond the Wagner studio. By 1900, Hoffmann was already teaching at the School of Applied Art in Vienna and was building up a thriving practice. A measure of his success was the commission to design a sanatorium at Purkersdorf, to the west of Vienna, which was effectively a spa hotel for prosperous Viennese society. Abandoning the Jugendstil curves that had dominated his work only a few years earlier, Hoffmann’s design was sportingly austere and strictly geometric in both plan and elevations. The institutional quality of the spaces were softened, however, by the tastefully restrained interior furnishings, which had been commissioned from the Wiener Werkstätte. The collection has three sketch plans (DMC 1900, 1901, 1902), two more detailed plans (DMC 1898, 1899) and a front elevation (DMC 1897). Hoffmann’s progress over the following decade from local to international eminence is represented by the Austrian Pavilion for the epochal exhibition of the German Werkbund, held in Cologne in 1914 but cut short by the outbreak of war (DMC 1855). While the exhibition is famous for Gropius and Meyers’ model factory and Bruno Taut’s Glass Pavilion, both powerful harbingers of the architectural world to come, Hoffmann’s pavilion was a very elegant exercise in minimalist classicism: the gable end of the pavilion as built urged that: ‘Beauty is the perfect harmony of the sensual with the spiritual.’ As a contemporary critic exclaimed: ‘The means are the simplest conceivable, but the effect is absolutely stunning.’[10]

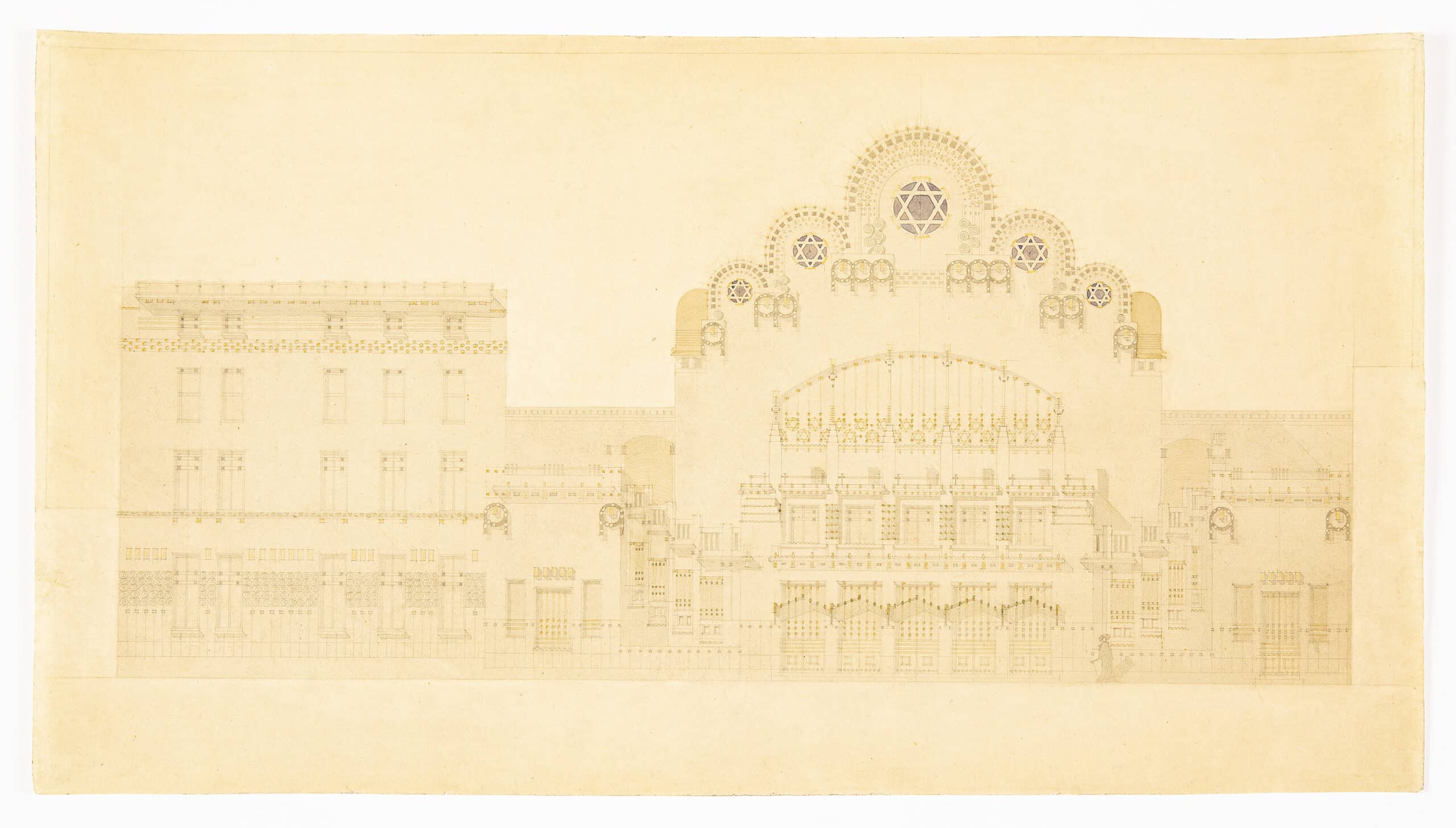

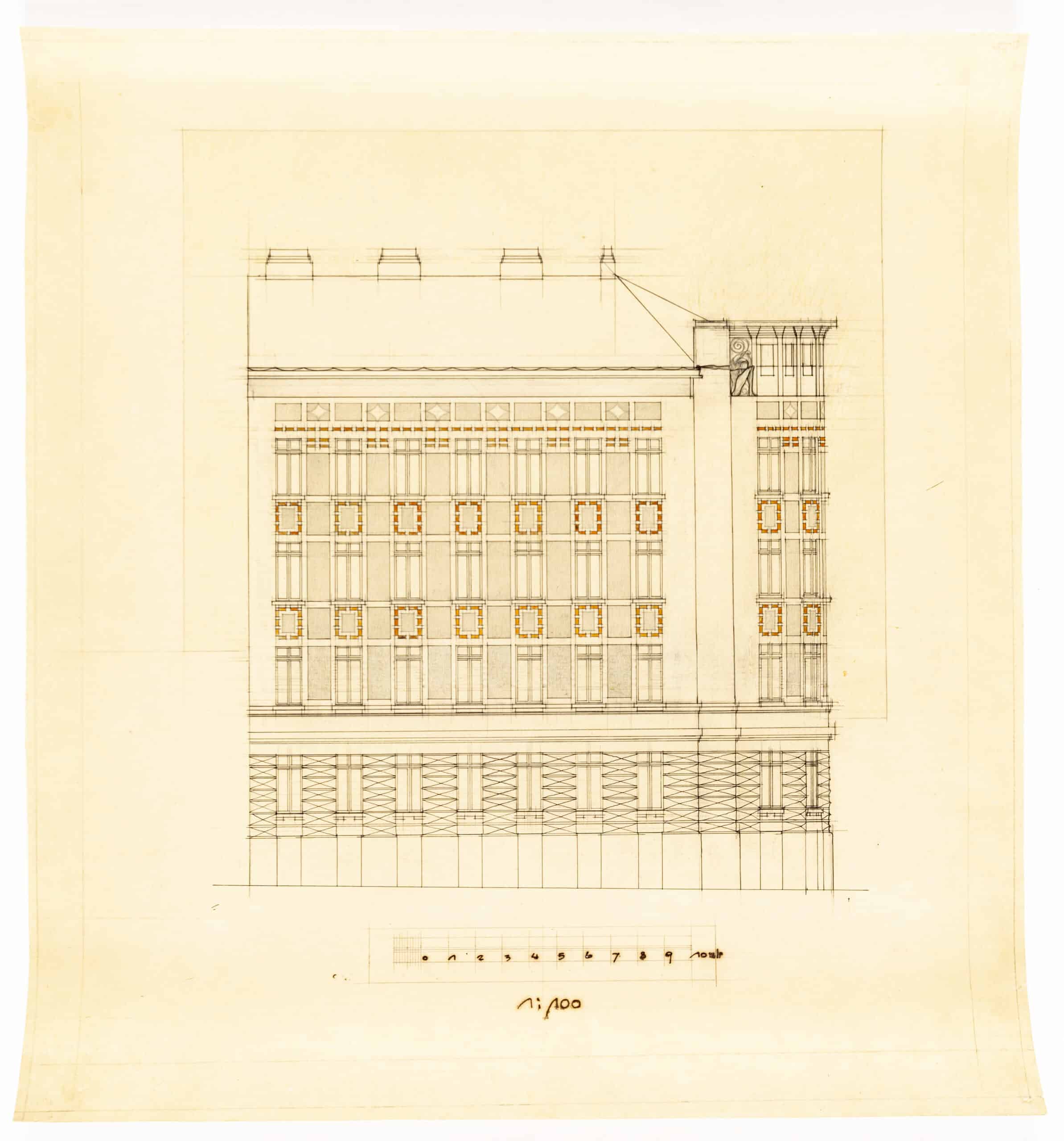

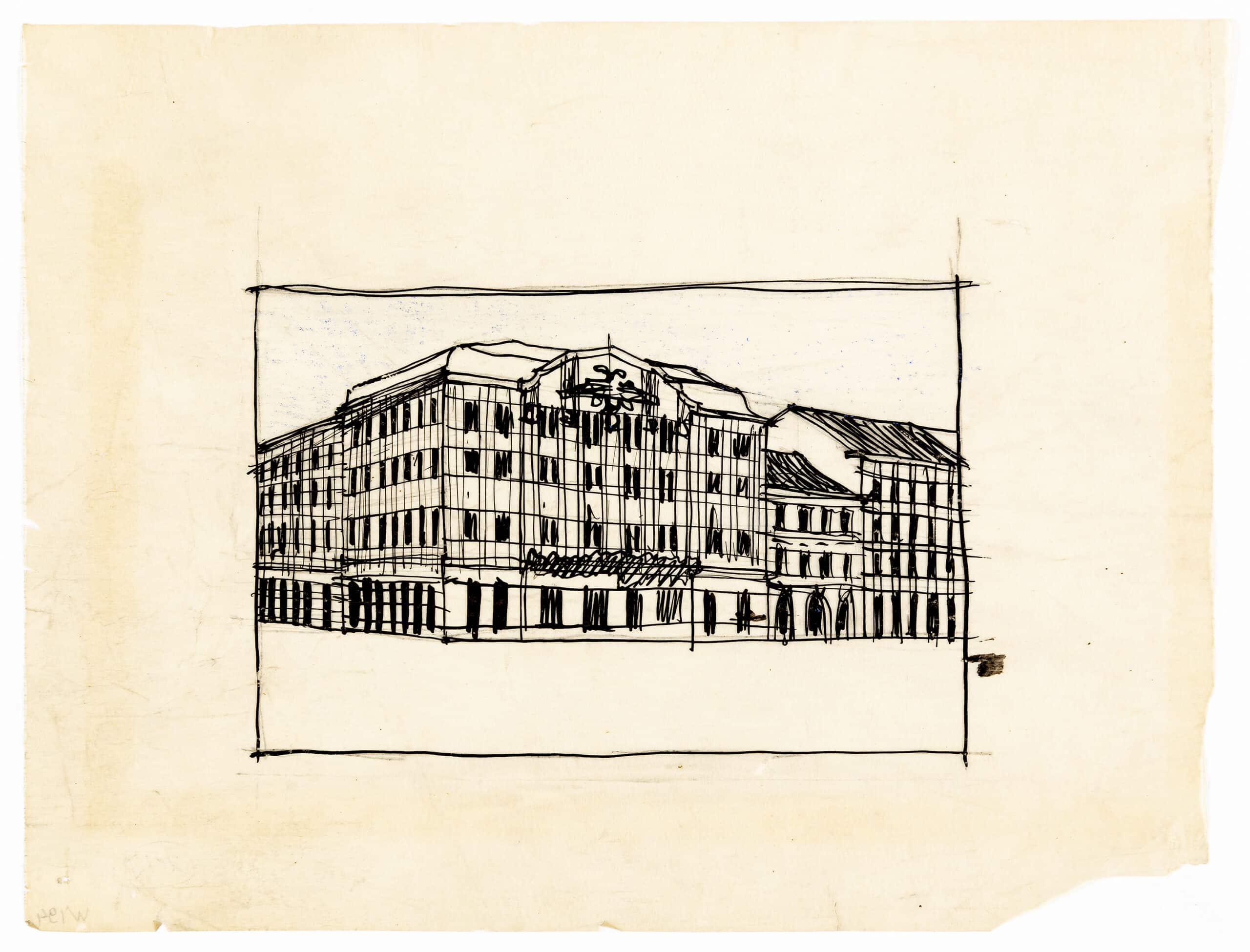

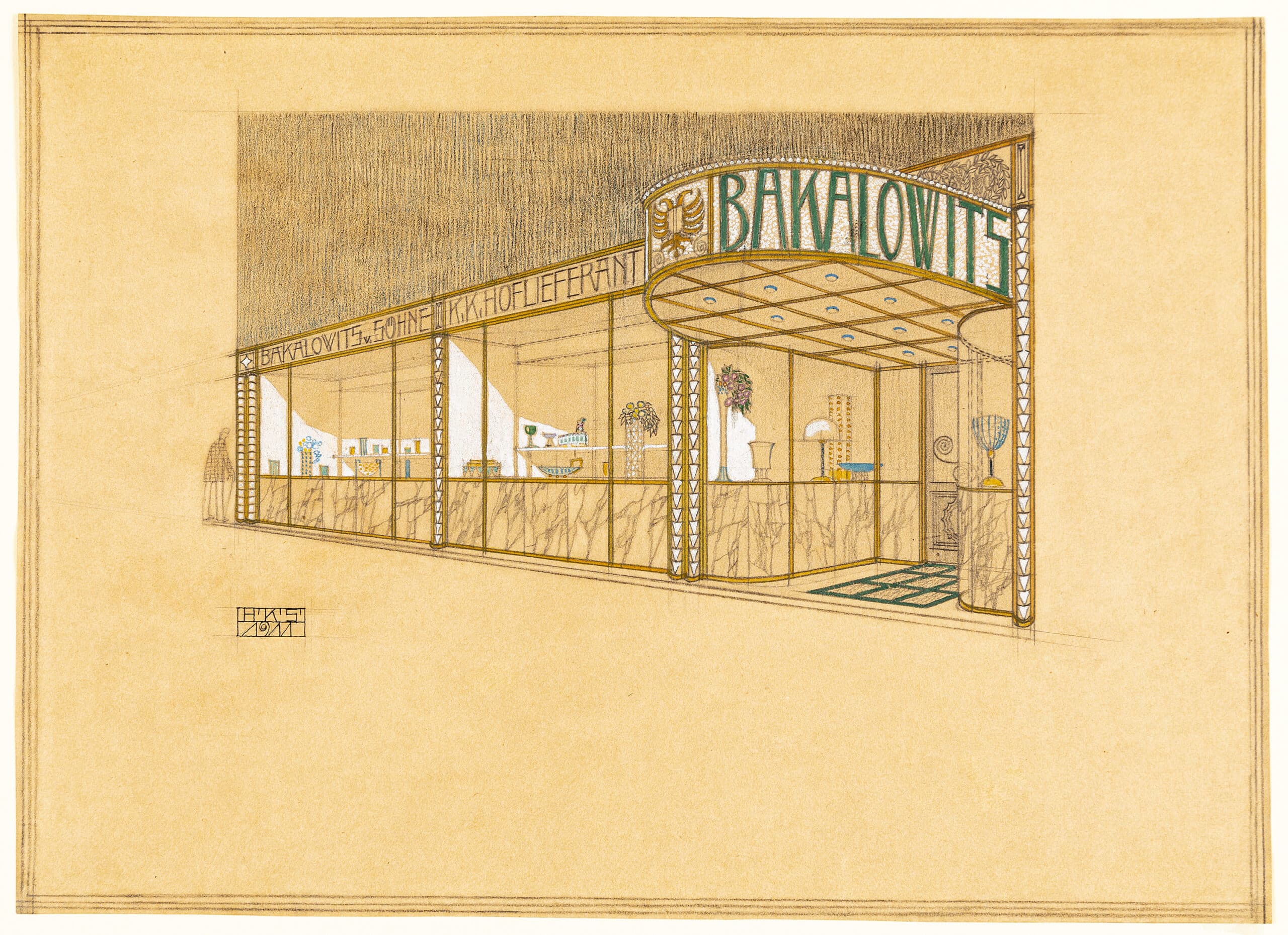

Hoppe, Kammerer, and Schönthal also enjoyed notable success in prewar Vienna. They initially worked in loose association on their own projects. While still assisting Wagner, for example, Schönthal produced a competition design fo a synagogue in Trieste, which was clearly indebted to the Steinhof Church (DMC 1923-1928). Hoppe, in contrast, focused more on domestic design, either villas (DMC 1944) or apartment houses (DMC 1940, 1951), several of which were built. In 1909, the three associates formalised their activities as one practice, Hoppe/Kammerer/Schönthal, with an office in the Ungargasse. While historians have found it convenient to portray early twentieth-century Vienna as a failing city, waltzing its way towards extinction, it was, in reality, booming in 1910 and the second largest city by area in Europe, following the incorporation of the industrial suburb of Floridsdorf in 1905. For the architects, the newly modernising Vienna was a city with great prospects. As Schönthal wrote in 1908: ‘If we think back to twenty years ago, we can measure how far behind us we have left the age of stereotyped design. Our thanks for this are due, above all, to Otto Wagner. For it was he who cleared away the rubbish, or the degrading business of copying, and shook the multitude out of their indolent slumber.’[11] For the Hoppe/Kammerer/Schönthal practice, this opened the way for more ambitious projects, which included several large office blocks in the city centre (DMC 1954), an appropriately dazzling shopfront and interior in the Spiegelgasse for the glass manufacturer Bakalowits (DMC 1953), and an unbuilt scheme for a massive holiday resort on the Adriatic coast at Abbazia, now Opatija, Croatia (DMC 1955).[12] In its scale and ambition, this last-named project expressed exactly the master’s ambition to ‘fan into bright flames the divine spark of fantasy.’

Additions and amendments are welcomed at editors@drawingmatter.org

*

Notes

- Constantin von Wurzbach, ‘Hügel, Karl Alexander Freiherr’ in Biographisches Lexikon der Kaiserthums Oesterreich, vol. 9 (Vienna: Kaiserlich-Königliche Hof- und Staatsdruckerei, 1863), 402.

- Von Hügel (above) helped Metternich escape from the uprising in Vienna by traveling with him to London in the spring of 1848.

- Otto Wagner, Inaugural Lecture to the Academy of Applied Arts, Vienna, 1894, quoted: Iain Boyd Whyte, Emil Hoppe, Marcel Kammerer, Otto Schönthal: Three Architects from the Master Class of Otto Wagner (Cambridge MA.: MIT Press, 1989, 24.

- Eduard F. Sekler, Josef Hoffmann: The Architectural Work (Princeton N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1965), 17.

- For a detailed account, see Sekler, ibid., 18-24.

- Josef Hoffmann, ‘Architectural Matters from the Island of Capri’ in Sekler, ibid., 479.

- Otto Schönthal, ‘Friedhof Projekt’ in Wagnerschule 1901 (Vienna: Jasper, 1902), 15.

- For a detailed account, see: Iain Boyd Whyte, ‘Antonio Sant’Elia un Wagnerschüler in absentia’, in Antonio Sant’Elia: l’architettura disegnata, exhibition catalogue (Venice: Commune die Venezia/ Venice Biennale, 1991), 73-87.

- Joseph August Lux, Otto Wagner (Munich: Delphin), 150.

- A. Heilmeyer in: Kunst und Handwerk, 64 (1913-1914), p. 275. Quoted, Sekler, above note 2, 159.

- Otto Schönthal, ‘Die Kirche Otto Wagners’ in Der Architekt, 14, 1908, 1. See also Iain Boyd Whyte, ‘Vienna Between Memory and Modernity,’ in Eve Blau and Monika Platzer (eds.), Shaping the Great City: Modern Architecture in Central Europe, 1890-1937 (Munich: Prestel, 1999), 125-135.

- For further details see Iain Boyd Whyte, Emil Hoppe, Marcel Kammerer, Otto Schönthal, 67-92.

Iain Boyd Whyte is Professor Emeritus of Architectural History at the University of Edinburgh. He has published extensively on architectural modernism in Germany, Austria and the Netherlands, and on post-1945 urbanism. A former Getty Scholar, he was co-curator of the Council of Europe exhibition Art and Power, shown in London, Barcelona and Berlin in 1996/97. He is the founding editor of the journal, Art in Translation, has served as a Trustee of the National Galleries of Scotland, and in 2015–2016 was Samuel H. Kress Professor at CASVA, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.