Wolkenbügel: El Lissitzky as Architect

– Richard Anderson and Markus Lähteenmäki

It was in a room without windows and walls of bare concrete, in the basement of one of the ETH buildings on its suburban campus in Hönggerberg Zürich, where I first heard about this book project from its author. Not another book on El Lissitzky, I remember thinking, when he told me about it. A book on Wolkenbügel already exists, done by Christoph Bürkle and Werner Oeschlin here at gta, I thought as he continued to explain. Having myself already combed the same files in the gta archives that he was now studying, I thought that, at least, there was nothing interesting to be discovered here. Now, with the book in front of me, I can happily admit that I was wrong on all accounts.

Richard Anderson’s Wolkenbügel: El Lissitzky as Architect is an exemplary re-evaluation of a classic, a study that will act as required reading for anyone interested in Soviet and European avant-garde architecture. The beauty of the book is in its unassuming curiosity, determination to leave no stone unturned, and an eye for the unexpected. In this, it is not unlike the subject it tries to capture, which is bigger than the one building, or ‘architectural idea’, as Anderson calls it (p.13), the ‘Wolkenbügel, aka. the horizontal skyscraper.’ The project itself was, as Anderson states, based on circulation, of ideas and people. It is a complex proposal that grew out of a complex oeuvre of a visionary artist, and out of collaboration with many others, including Swiss architect Emil Roth, who made designs for the projects architectural-tectonic execution. A pinnacle of 1920s artistic and architectural internationalism and visionary thinking, this ‘architectural idea’, has captivated many.

Wolkenbügel is an attempt to apply the radical approach of the artistic avant-gardes to architecture. It is an architectural application of dadaist tactics of acceleration and overturning, a translation of suprematist forms and rigour to rethink art from its basic elements put into the use of rethinking of how a city works as a space for a revolutionary society. The idea itself, turning a vertical into a horizontal, not only rethought the very basic concepts and coordinates through which to think of design for a building, but it did the same for the city. Elevating its volumes high above the ground and embracing the city with its long legs that formed passageways at transit hubs, it rethought the idea how a building directs the city. An idea of many iterations, proposed at key junctures of Moscow’s historic urban fabric, it made a revolutionary, but pacifying gesture, bringing new order amongst the chaotic old city. Going much further than Otto Wagner or others in such idea of how new urban arteries create a metropolitan environment, it also presented an idea of a new kind of building as a gate or a triumphal arch that activates the city by concurring new technologies of transport and communication and new principles of mobility and equality. With a single idea, where the new ideas of art, technology and society crystallised, Wolkenbügel proposed to rethink how a historic, medieval, Christian, and imperial city, could be reconceived as revolutionary, socialist, and modern. Importantly, it proposed to do it by binding and building on the historic fabric, using a precise insertion of these new kind of condensers of life and circulation to re-tune the city, rather than erasing and rebuilding it anew.

In Anderson’s book the genesis and afterlives of this project lend themselves to a thorough discussion of architecture in general—what it is, what it should be and how it is made. The book circles around El Lissitzky’s idea, approaching it, just as it was designed to be approached, from every angle, walking in and through, up and down, along and around it to narrate a much bigger story of culture and design practice. At a time when architecture as a visionary field was seen to hold keys to the question of how we should live together, not only as individuals, but as a society. Using this one project as a prism, Anderson lays out a history of architectural culture that was networked across the globe and unfolded in multiple media, driven by a belief that art and architecture would be crucial in building a better functioning, more equal, mobile and beautiful world.

A lot has been said about El Lissitzky previously. He said a lot himself and his work was a staple of 1920s publications of the international avant-garde, many of them also designed by him. Then, with a few decades of more quiet and secluded interest within small circles of scholars and collectors, the monumental book El Lissitzky: Life, Letters, Texts edited by his widow Sophie Küppers-Lissitzky and published in German and English, together with translation of his own originally German language 1930s book Russia: Architecture for a World Revolution into English in the 1960s lit his flame again cementing him as a central figure in the renewed interest in ‘Russian’ and Soviet avant-gardes. ‘Russian’ written in quotes here, because although it was branded at such, in fact it was a multi-ethnic and -national movement, well exemplified by Lissitzky himself, who was born as Lazar Markovich Lissitzky in the Smolensk region of Western Russia in 1890 in a Lithuanian Jewish family, with Yiddish as his first language. Since his ‘re-discovery’ in the 1960s and increasing number of exhibitions of Soviet avant-garde in Europe and the US from the 1980s onwards, an entire generation of art historians rethinking the discipline while writing about avant-garde took him as theirs. Books, articles, and exhibitions by John Milner, Peter Nisbet, Christina Lodder and others documented his role as a star of the international art scene. While articles by Yves-Alain Bois and Benjamin Buchloh gave him a prime of place in a story of radical rethinking of art and its ways to take effect in society, written as and very much inspiring an attempt to rethink the very basis of the discipline of art history itself. The 2003 book Situating El Lissitzky edited by Nancy Perloff and Brian Reed gathered many of those scholars and their disciples to provide a multifaceted analysis of this bright but often elusive figure.

Most recently, there has been continued interest in El Lissitzky’s work both in Russia and in the West. In 2022, his 1930 book Russia was published in Russian translation edited by Dmitry Kozlov, who has written on Lissitzky in his other books as well. Over the past decade exhibitions have displayed his work from new angles and in new scale. Utopia and Reality: Ilya & Emilia Kabakov – El Lissitzky at Van Abbe Museum and the Hermitage in 2012-2013 juxtaposed his work with the more recent leading Soviet artistic figure. While a large retrospective that took place across two sites—Tretyakov Gallery and Jewish Museum—in Moscow in 2017–2018 displayed hundreds of drawings and paintings by him kept in Russian collections, also exhibiting many of his architectural designs for the first time.

In this lineage, it may indeed seem that claiming to provide a ‘new and definitive’ account of Lissitzky’s craft as an artist and architect, may seem a bit over the top. However, after reading the book, I happily sign it. How does the book do it? Looking back to the gta archives, I have to admire how much Anderson makes out of the documents there. Seen in isolation they don’t seem to be much. But, placed within a huge puzzle of fragmentary evidence from several countries and twice as many institutions, they start to speak volumes. This, exactly, is the key to the success and beauty of the book. Since Lissitzky’s work unfolded in large part in correspondence with Western actors, and since there has always been an active, international market for his work, a lot of important materials related to him are held in Western institutions: in particular at the Van Abbemuseum and the Stedelijk, but also in dozens other public and private collections. In Anderson’s book the material from the Russian collections now sits alongside material from various European and American archives, showing a fuller picture of the way he worked in drawing and writing. Not only has Anderson done a meticulous job of going through archival evidence, but he also really makes it sing by joining the dots and asking the right questions. Like Yves-Alain Bois before him, Anderson takes Lissitzky’s images as a guideline to the analysis itself, pushing the very boundaries of visual analysis of architecture, just as those images push the boundaries of how they communicate volume and space.

Markus Lähteenmäki did his MA at the Courtauld Institute with John Milner and wrote his doctoral thesis at ETH on early Soviet art and architecture. He is currently a Swiss National Science Foundation funded postdoctoral scholar at UCL. He once worked for Drawing Matter too.

The following text is an extract from the book, Richard Anderson, Wolkenbügel: El Lissitzky as Architect (MIT Press, 2024).

Circulation

The Wolkenbügel was born of the circulation of documents. El Lissitzky developed his project in letters exchanged with Emil Roth. Key decisions about the structure (e.g., three pillars, rather than four) were made based on the sketches, drawings, and recommendations that travelled between Roth and Lissitzky through the post. While drawings and information passed between the two correspondents throughout the design phase, once Lissitzky determined that the Wolkenbügel was complete he began systematically distributing images of it through multiple channels. This activity amounted to the converse of the effort that he, Sophie Küppers, and Hans Arp had put into the production of The Isms of Art: instead of making a collection of images and documents, the issue was now their dissemination. For Lissitzky, the process involved reproducing and scaling his drawings—shrinking, masking, and editing them along the way. It also required reproducing the drawings at large scale to be mounted and shipped for display in a variety of contexts. Together Lissitzky and Küppers managed the stock of originals and reproductions. They drew on this inventory as they sent images to friends, journals, and curators in a campaign to launch the Wolkenbügel into the world.

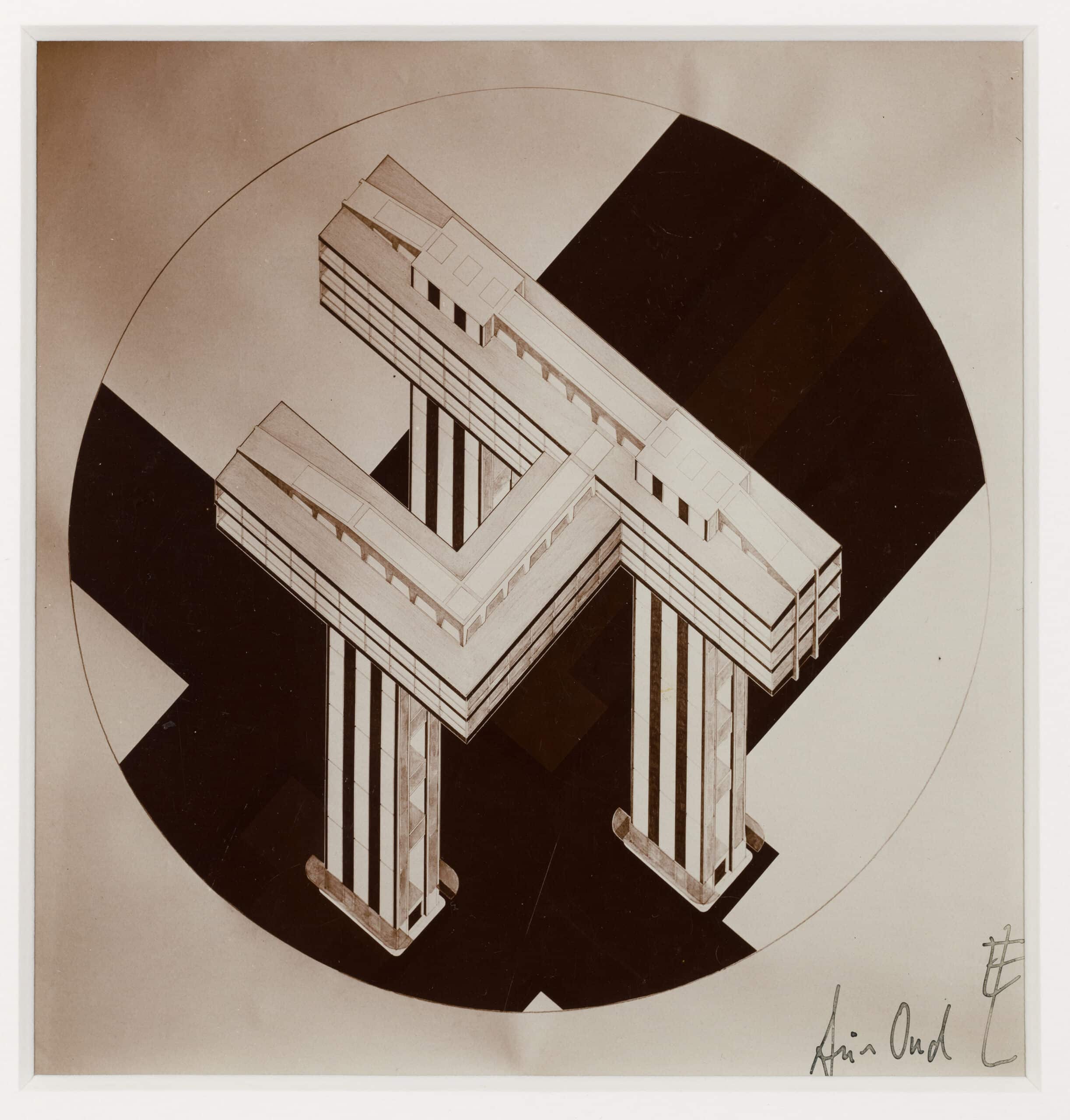

On the eve of his departure from Switzerland, Lissitzky sent prints of the Wolkenbügel drawings to his friends and collaborators. On May 14, he sent six reproductions to J. J. P. Oud: the axonometric, two perspectives, two elevations, and a composite sheet containing further elevations of a plan of the office floor.[1] He mailed a similar selection of images to Til Brugman, noting ‘right now I do not have any possibility of sending extra photos (as I promised) to [Cornelis] van Eesteren and [Gerrit] Rietveld; I ask you to share them—I’ll send more to you later.’[2] Comparison with the surviving drawings demonstrates the significant reduction in scale required to enclose the project in correspondence. The orthographic drawings in the Tretyakov Gallery were drawn on sheets approximately 50 × 65 cm.[3] The photographs sent to Oud vary slightly in size, and the largest is approximately 17 × 13 cm.

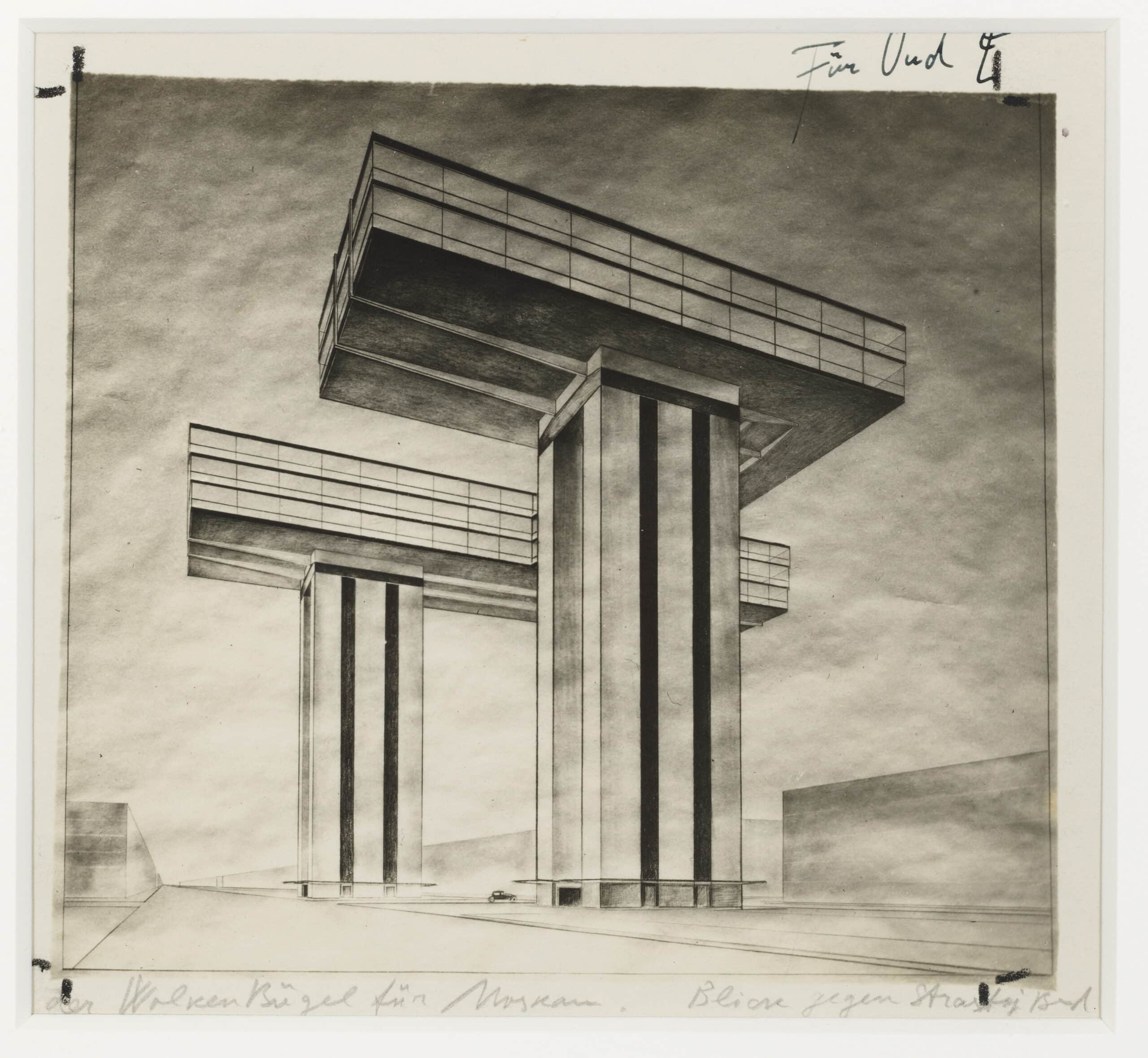

Many of the prints bear visible traces of the process of reproduction. Most grow darker toward the top of the image, with a concentration of shadows at the upper left. Such gradients point to the uneven distribution of light during the exposure of the plates, suggesting Lissitzky’s drawings were photographed in imperfect studio conditions. In the print of the perspectival view of the Wolkenbügel along the boulevard, the texture of the paper is acutely visible: bumps and minor creases have been accentuated by the directionality of the light falling over the drawing, lending the negative space around the structure a salient presence.

Lissitzky probably photographed the Wolkenbügel drawings himself. In May 1924, a year before he distributed images of the Wolkenbügel, he complained to Küppers that the photographer he commissioned to make reproductions of the Speaker’s Tribune for Behne’s book produced very faint images, noting that ‘I have to teach the photographer to make prints properly.’[4] By the time Lissitzky made his prints of the Wolkenbügel, Küppers had lent him her father’s large-format camera, which accepted photographic plates in 13 × 18 cm holders.[5] The scale and sharpness of the images Lissitzky sent to Oud correspond to this format, suggesting that they were one-to-one contact prints.

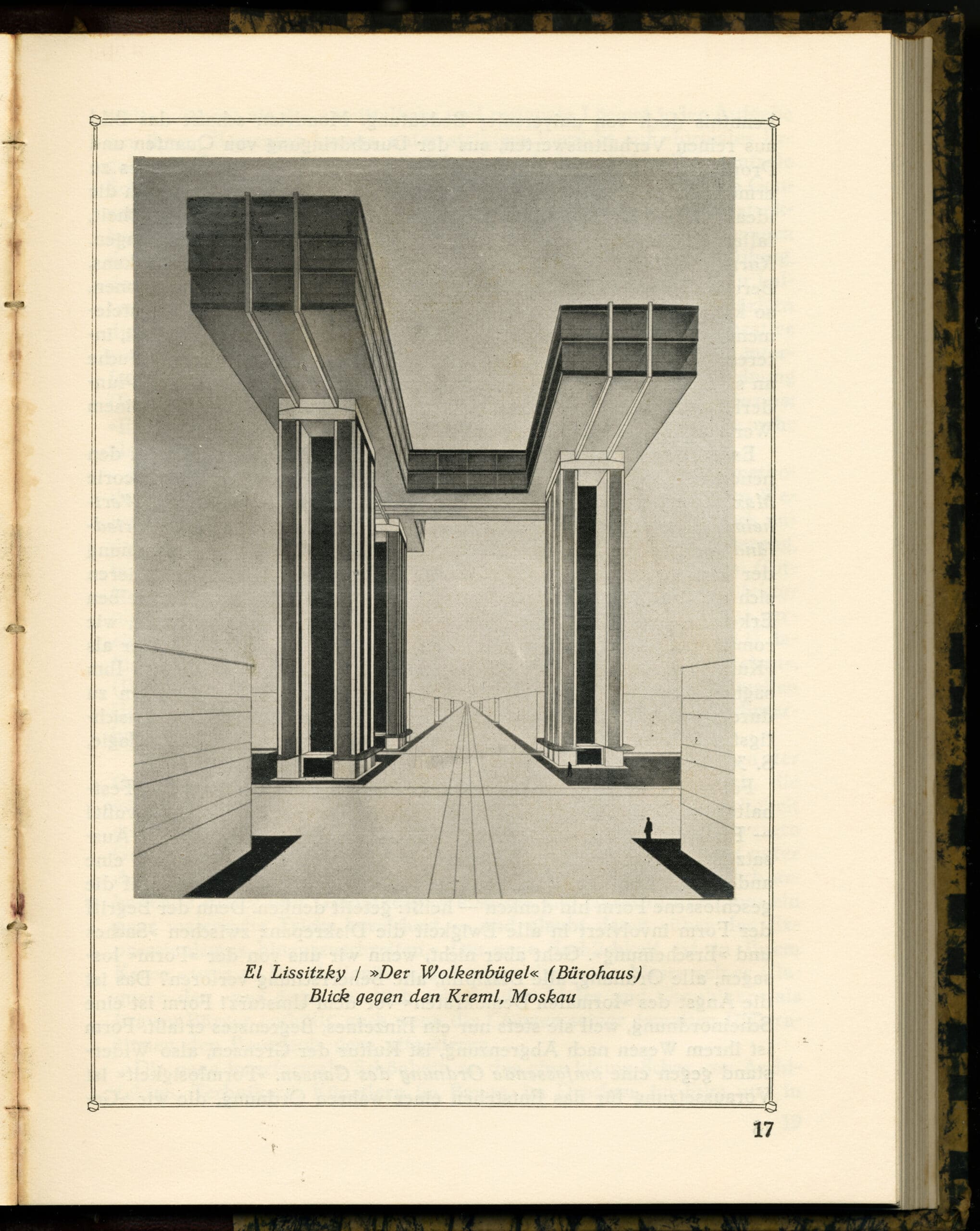

The size of the Wolkenbügel photographs facilitated both circulation through the post (as they could be easily enclosed in envelopes) and photomechanical reproduction. The first images of the Wolkenbügel to be reproduced were the perspectives, not the orthographic or axonometric drawings. The catalogue to the exhibition of the Novembergruppe of June 1925 was almost certainly the first publication to include an image of Lissitzky’s project. This exhibition was a pivotal event in Lissitzky’s effort to engage with European architectural circles and to bolster his standing within them. This effort extended to the care he took in the preparation of his images for print. The catalogue was published in Berlin as part of the series ‘Archiv der Deutschen Kunst [Archive of German Art],’ edited by Gustav Eugen Diehl.[6] It consisted of forty-eight unnumbered pages, and a cover printed on both sides. Thirty-two of the pages were devoted to plates of the paintings, sculptures, and architectural models and drawings included in the exhibition; the remainder comprised an illustrated checklist. The architecture section included photographs of executed buildings, architectural models, and drawings.

An advertisement on the back cover of the catalogue stated that the photographs for the publication were produced by the C. J. von Dühren and E. Henschel workshop for portrait and technical photography in Berlin.[7] While the workshop may have reproduced the paintings and sculptures in the catalogue, this cannot have been true for all of the architectural objects: at least one model reproduced in the catalogue was destroyed in transit, and it is unlikely that von Dühren and Henschel photographed executed projects anew.[8]

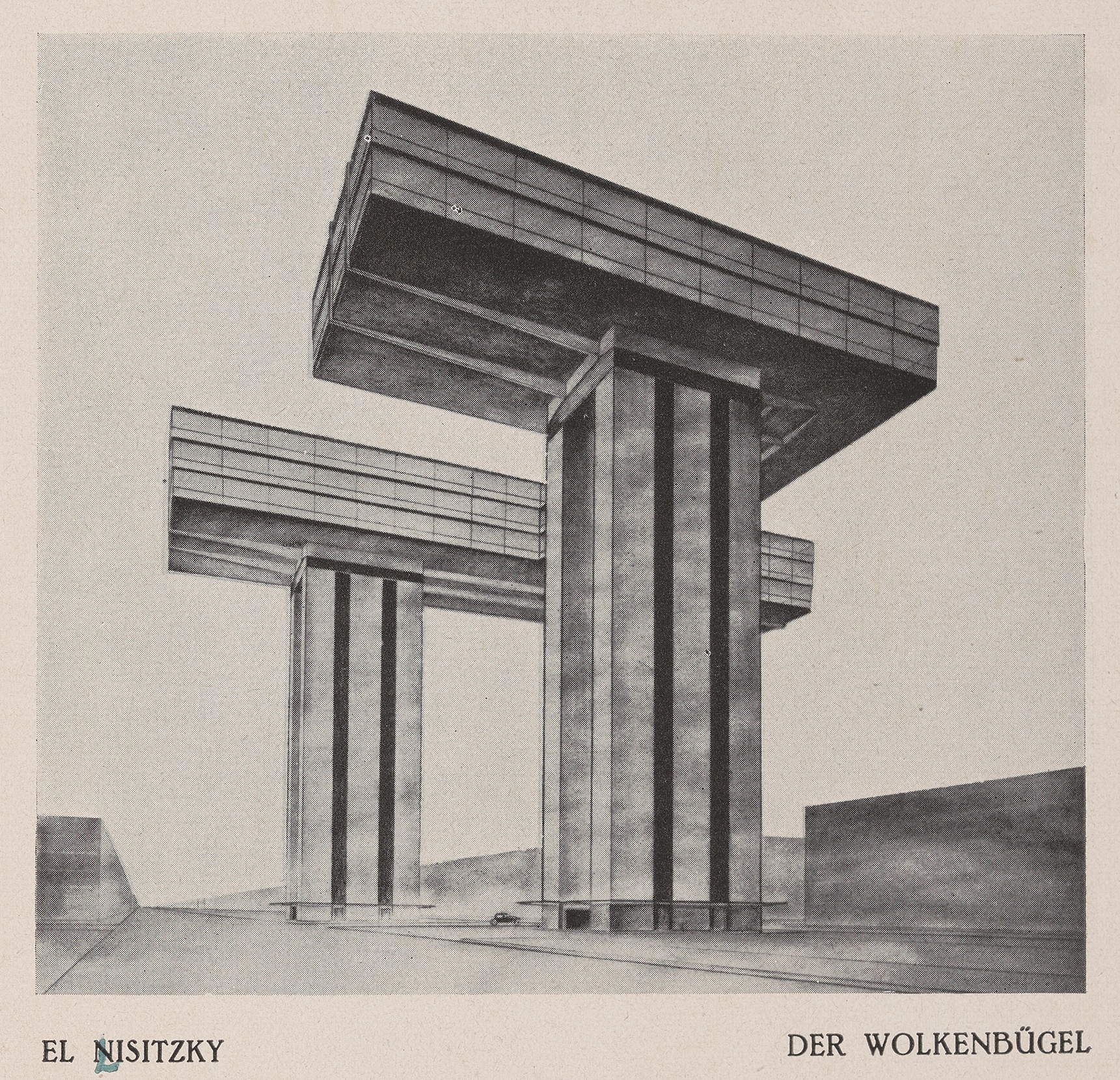

Three images of Lissitzky’s Wolkenbügel were shown in the Novembergruppe exhibition, either as original drawings or enlarged photographic prints: the perspective to the Kremlin, the perspective along the boulevard, and the axonometric view. The view of the structure along the boulevard was reproduced in the catalogue, printed with an unfortunate misspelling of its author’s name as ‘El Nisitzky.’ The reproduction shows the subtle manipulations Lissitzky made to his architectural imagery, highlighting the importance of montage practices to the circulation of his architectural work. A close comparison between the print of the view along the boulevard that Lissitzky sent to Oud and the image reproduced in the Novembergruppe catalogue reveals that they originated from the same source: a print from the batch of images made before Lissitzky departed from Switzerland. The two images share certain aberrations and printing defects. A white spot interrupts the dark line running up the right-hand side of the pillar in the background of Oud’s print; the same defect is visible in the half-toned print in the catalogue. Linear particles of dust are visible on the pillar in the foreground of the print for Oud; the ghosts of these foreign materials appear as textural deformations in the published image.

Oud’s photographic print and the published image are distinguished by the treatment of the negative space surrounding the Wolkenbügel. In the print, the ripples and swelling of the paper are highly visible; in the published version the sky is rendered in an even grey tone. When we zoom in very close to the printed version, subtle halo effects become noticeable: at the rear edge of the pillar in the foreground a faint line is visible to the left of the black line defining the building’s edge. This faint line extends upward and turns left where the underside of the lowest office floor obscures the sky from view. Visible at other hard edges throughout the printed image of the Wolkenbügel, these faint lines are tell-tale signs of image manipulation. They represent the seams where Lissitzky’s print has been clipped to eliminate the highly textured background of the initial photograph. In the process of creating a printing plate, the outline of the Wolkenbügel and the masses of the surrounding buildings were cut out with a blade and superimposed on a neutral background. The rippled texture of Lissitzky’s initial print remains visible on the glazed surfaces of the Wolkenbügel itself, but the background has been neutralized. Lissitzky may have worked with the von Dühren and Henschel photographic workshop in this process, but it is equally likely that he executed this manipulation himself.

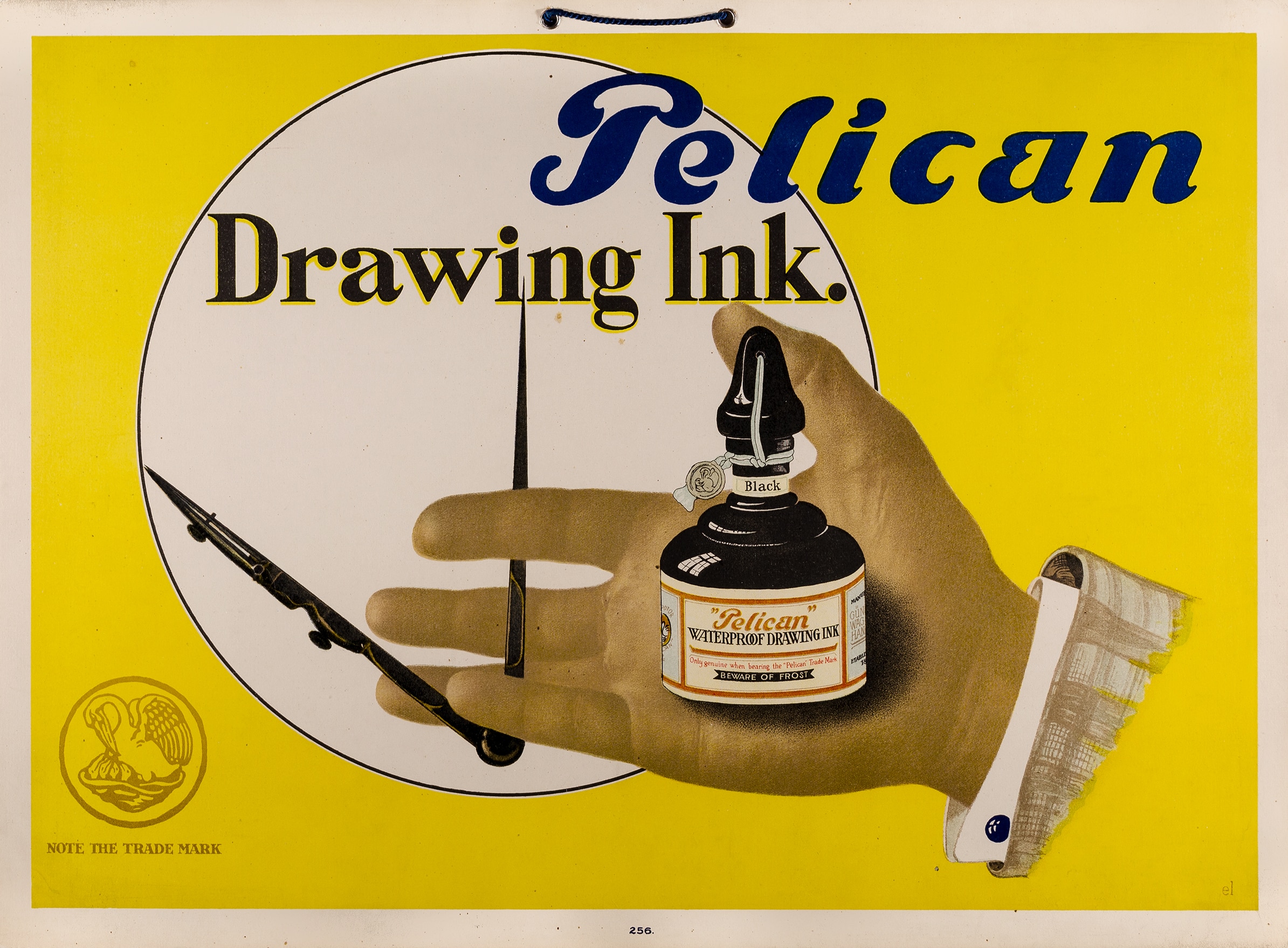

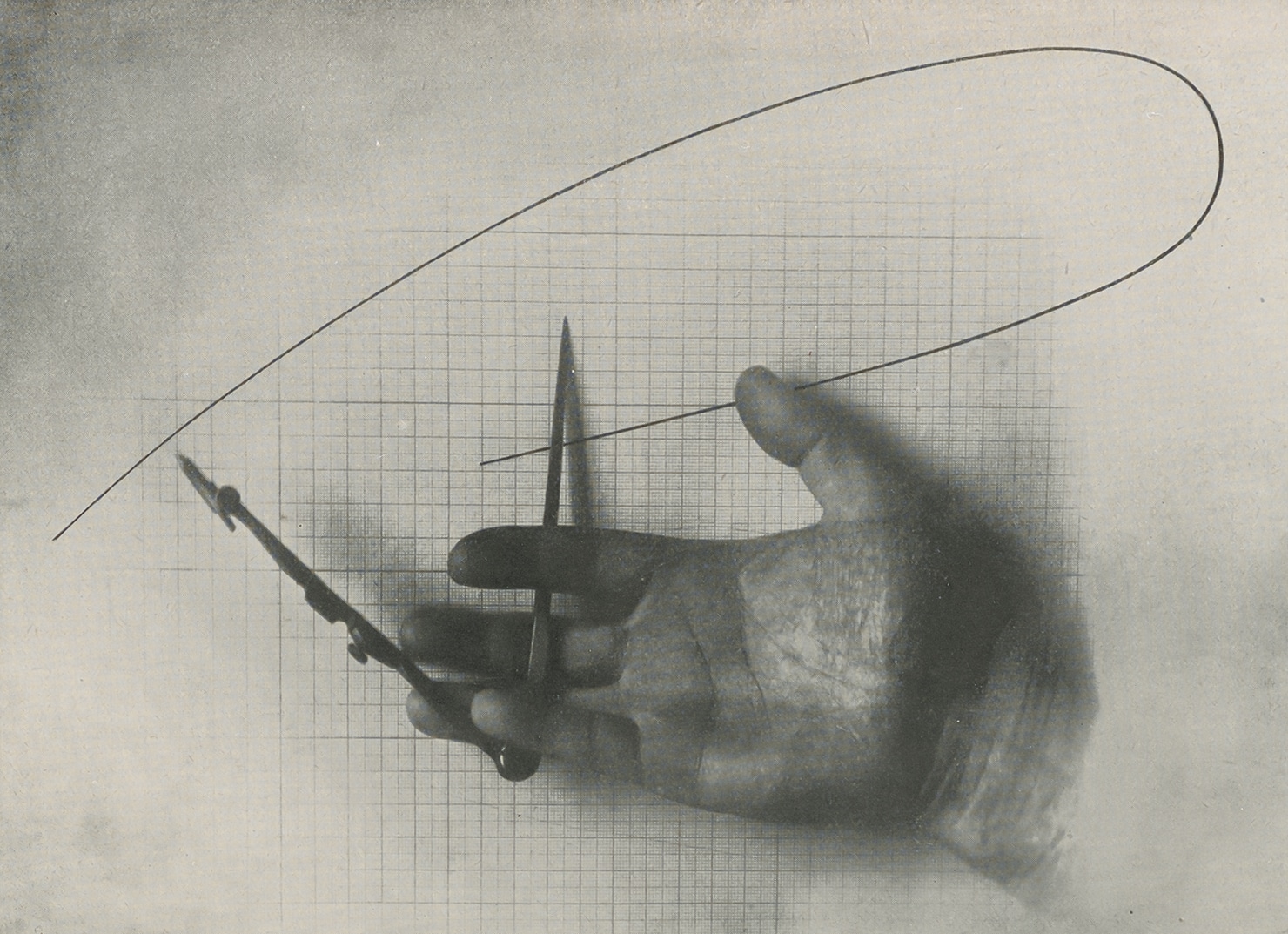

Such editing of architectural images was not an innovation in and of itself. Le Corbusier, for example, frequently published manipulated photographs of both his own buildings and found images. He consistently edited photographs for polemical effect, most memorably in the removal of ornamental features from images of grain silos from the Americas that he published in L’Esprit nouveau and Vers une architecture.[9] He also retouched photographs of his built work, such as the Villa Schwob, to remove background context and undesired elements, creating what Beatriz Colomina has called ‘faked’ images.[10] Lissitzky’s manipulation of the prints of the Wolkenbügel was less overt. He devoted his effort to clarifying the presentation of his project by heightening the contrast between figure and ground. In this, Lissitzky drew on the practice of masking, used to great effect in his advertisements for Pelikan. His manipulated print of the Wolkenbügel reiterated the process evident in his English-language poster for the brand, which featured a modified photograph of his own hand transposed onto a graphic background. This link between the presentation of the Wolkenbügel and Lissitzky’s advertising work is revealing. His manipulations were subtle, and he sought to avoid distortions. He evidently wanted to present the clearest possible image of his architectural idea, and he used the graphic prowess he developed through his work in advertising to prepare his images of the Wolkenbügel for circulation.

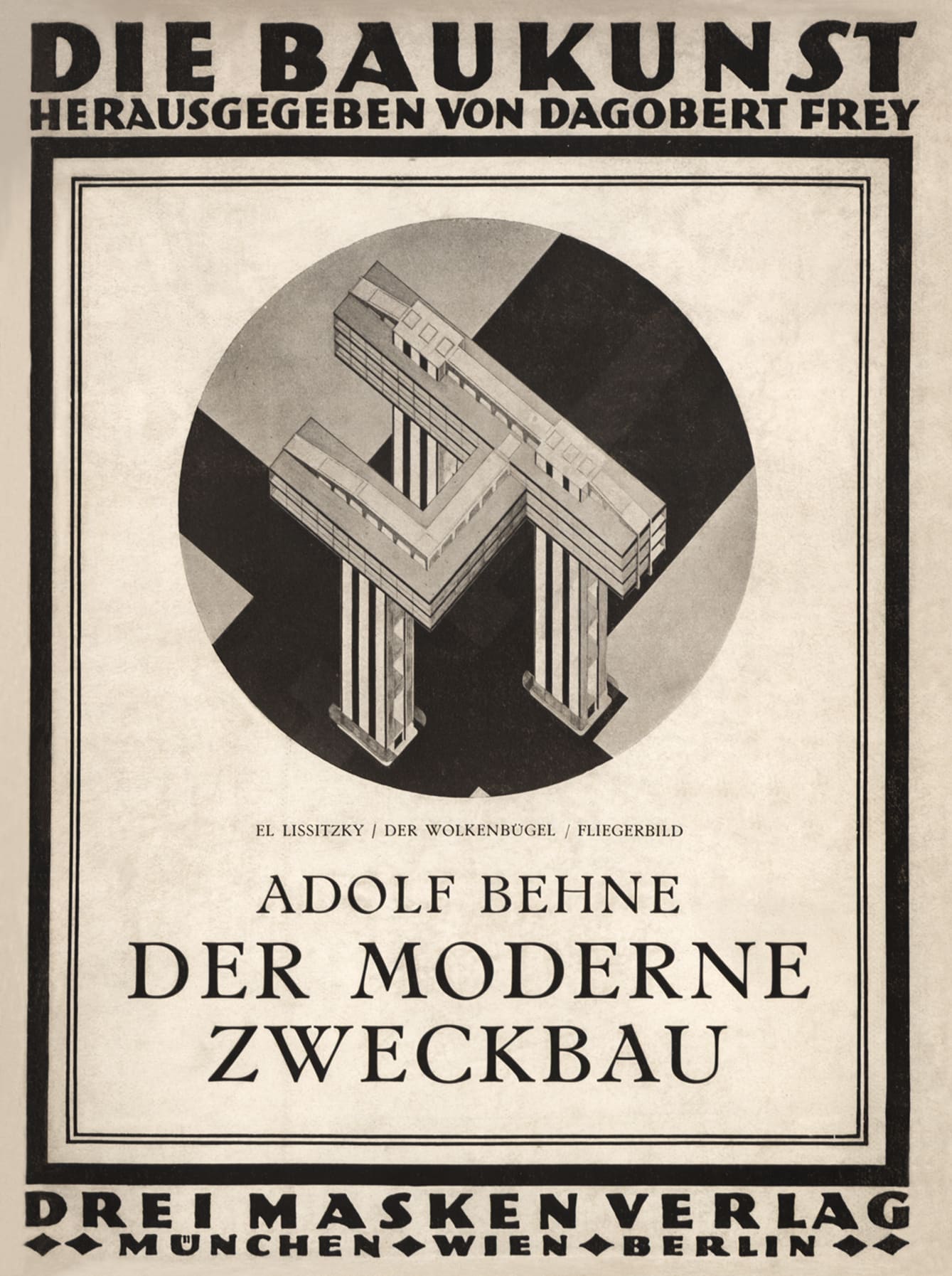

The format of the photographs of the Wolkenbügel drawings facilitated their reproduction in print. The image published in the Novembergruppe catalogue is 10 × 11 cm; the printed portion of the image Lissitzky sent to Oud shows the Wolkenbügel at approximately 11.4 × 12.6 cm. This consistent scale indicates that the printing plates made from Lissitzky’s image were produced at one-to-one, avoiding any need for re-sizing. Adopting a format suitable for publication allowed Lissitzky to retain significant control of the reproduction process by obviating the need for further manipulations. This pattern of one-to-one reproduction was repeated many times over, and it is manifest in the instances when Behne published images of the Wolkenbügel. In September 1925, Behne published an image of Lissitzky’s project in an extended review of The Isms of Art in the journal Faust.[11] While the Wolkenbügel did not figure in that book, Behne selected Russian work completed since the October Revolution to accompany his review because he felt that was a key contribution of the volume edited by Lissitzky and Arp. In addition to paintings by Wassily Kandinsky and Olga Rozanova, and a sculpture by Naum Gabo, Behne published the Wolkenbügel in the perspectival view toward the Kremlin. Lissitzky no doubt supplied a print of this image to Behne when he stayed with him in Berlin on his way back to Moscow. Faust printed illustrations as tipped-in plates, and the Wolkenbügel appeared as an image 14 × 11.4 cm, matching the size of the print Lissitzky had previously sent to Oud. The format in which Lissitzky circulated his images also expedited the use of the aerial view of the Wolkenbügel on the cover of Behne’s Der moderne Zweckbau. In the print of the drawing he sent to Oud, the diameter of the structure’s circular frame is approximately 11.4 cm, matching the scale of the image on the cover of Behne’s book.

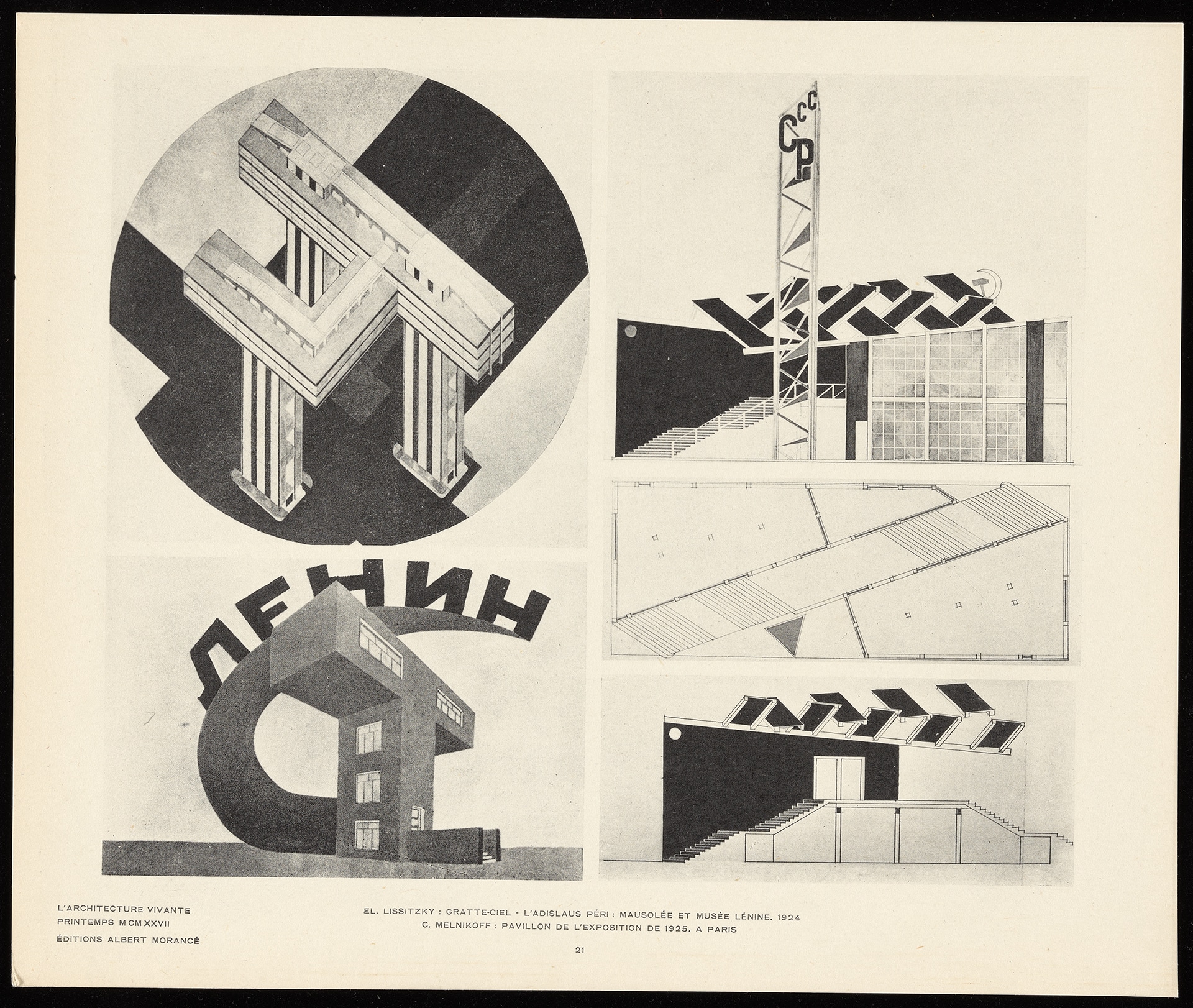

Lissitzky always intended the images of the Wolkenbügel to multiply. The scale and clarity of the Wolkenbügel prints, derived from 13 × 18 cm photographic plates, lent themselves to the formats of the journals and the books where he disseminated his work. Lissitzky’s self-conscious and subtle engagement with the practices of reproduction (printing, scaling, masking, clipping) enabled the dissemination of the Wolkenbügel by rendering such banal acts as the production of printing plates and editorial image placement frictionless and self-evident. By adapting his images to the medium of their reproduction (i.e., print), Lissitzky was able to maintain control of the quality of his images while creating the preconditions for their proliferation. The effects of this strategy soon yielded results when images of the Wolkenbügel began to circulate without Lissitzky’s direct involvement. The drawing of the Wolkenbügel on the cover of Behne’s Der moderne Zweckbau is a case in point. Soon after its publication, the Wolkenbügel appeared as a reproduction from Behne’s book cover in the Brno-based publication Pásmo and in Karel Teige’s account of the art of the USSR following his visit in 1925.[12] In the following year, the same image would be reproduced from Behne’s book in Fronta, also published in Brno, and in L’Architecture vivante.[13] 40 Lissitzky initiated the circulation of the Wolkenbügel in print publications in 1925 on his own terms, and it has not stopped to this day.

Notes

- The photographs were enclosed in the following letter, which also included Lissitzky’s hand-drawn plan of Moscow: Lissitzky to Oud, May 14, 1925, Brione/Locarno, VAM, 1583-8.

- Lissitzky to Brugman, May 14, 1925, Brione, RKD, Til Brugman Archive, NL-HaRKD 0607.47.

- See, for example, drawings RS-1912, RS-1913, and RS-1914 in the State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

- Lissitzky to Küppers, May 21, 1924, Orselina, in El Lissitzky: Maler, Architekt, Typograf, Fotograf, ed. Sophie Lissitzky- Küppers (Dresden: Verlag der Kunst, 1967), 47.

- Lissitzky-Küppers, El Lissitzky (1967), 48.

- Ausstellung der November-Gruppe in den Räumen der Berliner Secession, Archiv der Deutschen Kunst (Berlin: K. Ullrich, 1925).

- Advertisement for the Werkstatt für Bildnis- u. technische Photographie C. J. von Dühren und E. Henschel in Ausstellung der November-Gruppe in den Räumen der Berliner Secession, cover, verso.

- While Walter Gropius and Adolf Meyer’s model for a kindergarten in Bad Liebenstein is reproduced, the catalogue indicates that the model was destroyed in transport, suggesting that Gropius had supplied an image for reproduction. The same was almost certainly true for the built work presented by Otto Bartning and Hans Poelzig.

- On Le Corbusier’s manipulation of these images, see Reyner Banham, A Concrete Atlantis: US Industrial Building and European Modern Architecture, 1900–1925 (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1986), 215–228.

- See Beatriz Colomina, Privacy and Publicity: Modern Architecture as Mass Media (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1994), 107–118.

- Adolf Behne, “Von der formalen zur funktionalen Kunst-Revolution,” Faust 4, no. 3 (1925): 11–20.

- See A. Černík, ‘Moderní účelová stavba,’ Pásmo 2, no. 6–7 (1926): 77; Karel Teige, ‘Dnešní výtvarná práce sovětského Ruska,’ in SSSR: Úvahy, Kritiky, Poznámky, ed. Bohumil Mathesius (Prague: Čin, 1926): plate 16.

- Fr. Halas, Vl. Průša, Zd. Rossmann, and B. Václavek, eds., Fronta: Mezinárodní sbornik soudobé aktivity (Brno: Fronta, 1927), unpaginated, plate 91; L’Architecture vivante, Spring 1927, plate 21.

Richard Anderson is Professor of Architectural History and Theory at the University of Edinburgh. He is the editor of Ludwig Hilberseimer’s Metropolisarchitecture and Selected Essays and the author of Russia: Modern Architectures in History.

– Reinier de Graaf