The Poetry of Concrete

The following text is reproduced from the catalogue to Lina Bo Bardi: The Poetry of Concrete, an exhibition of the architect’s drawings at the Tchoban Museum for Architectural Drawing, Berlin (1.06.2024 – 22.09.2024). Find more information, and purchase the catalogue, here.

I was born in Rome, in Prati di Castello, a suburb that arose when the city became the capital of Italy.[1]

I never wanted to be young. What I really wanted was to have a history. At the age of twenty-five I wanted to write memoirs, but I didn’t have the material.

My guardian angel was a soldier. In Via Stefano Porcari, in the Pianciani Primary School, our teacher announced that ‘there will be no classes for one week. The soldiers are going to be billeted here.’ So soldier Giocardelli was installed in the school. He was a guardian angel and stayed on for a number of years.

When I was a child I used to go to Bordighera, on the border with France, Nice, Cannes. Sometimes I would be taken to Abruzzi to visit my maternal grandfather. He was a doctor and lived in Tagliacozzo, in an old, very pretty house. At other times we would go to the beach at Ostia, near Rome.

When I was a youngster I used to go to variety shows, against my mother’s wishes. I had an uncle who was a journalist and he would take us. We got to know the actors, such as Petrolini. I would also go to the movies as often as I could. I saw great German, American and French films. In those days the Italian cinema was very backward and we found it tedious.

I graduated from the College of Architecture at the University of Rome. The tendency of the College, whose rectors were Gustavo Giovannoni and Marcello Piacentini, was towards the historical-architectural disciplines, thought to be more important than composition. The fact that Rome is one of the centres of classical culture resulted in the students spending most of their time studying ancient monuments.

I came from the Artistic Lyceum, four years of architectural-artistic preparation, the theory of shading and geometric drawing. Because of the style of courtly ‘nostalgia’, not only at the University but also in the entire ambience of professorial Rome, I fled to Milan.

I ran away from the ancient ruins restored by the fascists. Rome was a city that had stopped, it was where fascism was. All Italy was somewhat stopped. Except for Milan.

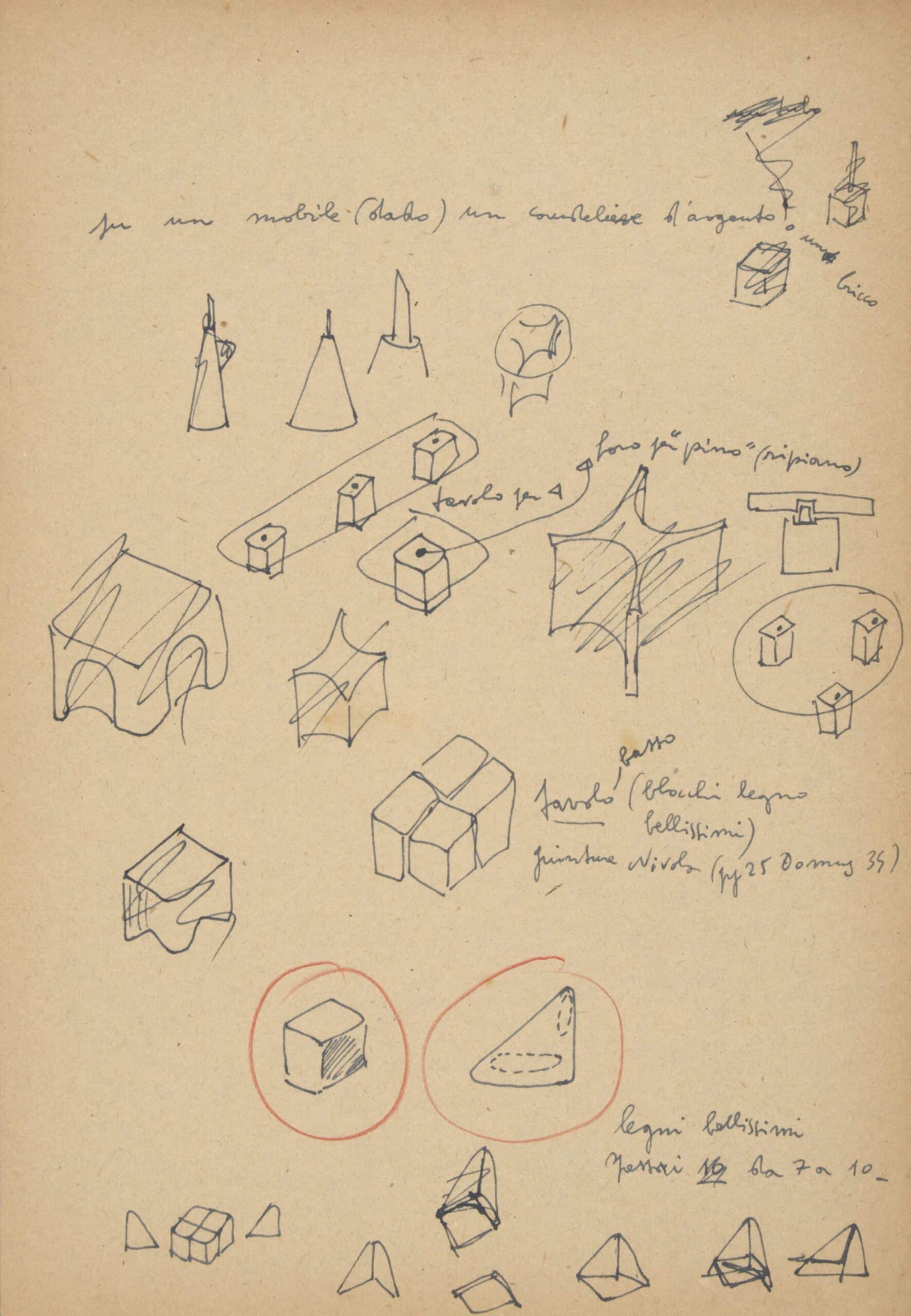

In Milan, to ‘acquire practical experience’ I entered the office of the celebrated architect Gio Ponti, the leader of the movement that advocated Italian craftsmanship, director of the Triennale di Milano and publisher of the magazine Domus. He said right away: ‘I’m not going to pay you, you have to pay me’.

Work was from eight in the morning till midnight, Saturdays and Sundays included. The work ranged from the designing of teacups and chairs and fashions (that is, clothing) to urban projects such as the Abano (a spa in Veneto). Activities in the office tanged from the construction of the Montecatini to organizing the Decorative Arts Triannuals and editing magazines. So I came into direct contact with the real problems of my profession.

Gio Ponti described himself as being the ‘last of the humanists’. His enemies, on the ‘Casabella’ side of the architect Giuseppe Pagano, would say: ‘Certainly the last’.

The outbreak of war, right after the 1940 Triennale, in which I took part anonymously as Ponti’s assistant, presented other problems: one could no longer build and the field of ‘practice’ was replaced by ‘theory’. I had my own professional office in Milan, but the number of jobs, which had become problematic due to air raids, led me to take up work as an illustrator for important Milan magazines and newspapers, among them the Stile, founded by Gio Ponti, who had by then left the management of Domus.

From 1941 to 1943 I carried on an intense journalistic campaign, contributing to popular weekly magazines such as Tempo, Grazia and Vetrina. I also edited the Quaderni di Domus collection, where I engaged in research on craftsmanship and industrial design. And I began to work for Illustrazione Italiana. I lived at Principe de Savoia Hotel.

July, 1943. Fascism fell apart. During the bombardment on 13 August I lost my office. I left Ponti’s great studio-office and was invited to run Domus. I took on the job in the midst of the World War and the German occupation.

In Bergamo, where Domus had its wartime headquarters, working alone and with the help of old publications, I organised the magazine issues until Domus was suspended by order of the Republic of Salò.

In wartime, one year corresponds to fifty years of peace, and the judgement of humans is a judgement for future generations. Among the bombs and machine guns, I took stock and decided that the important thing was to survive, preferably unscathed, but how? I felt that the only way was to be objective and rational, an extremely difficult path to take when the majority of people opt for literary and nostalgic ‘disappointment’. I felt that the world could still be saved and made the better, and that this was the only task worth living for, the starting point for survival. I joined the Resistance, the clandestine Communist Party. I saw the world around me only as an immediate reality and not as an abstract literary exercise.

The House of Man fell down: in Italy, along the Aurelia and the Emilia, in Sicily and Lombardy, in Provence and Brittany; the House of Man fell down in Europe. We did not expect it to disappear thus: it was secure, it was a ‘fortress’; had there ever been anything stronger than this ‘house’? It had been there for years, every year there were changes, it was a daughter, a new generation that arrived, the plush sofa with fringes from the 1800s which disappeared and was replaced by a piece of ‘English’ of furniture in mahogany and sky- blue-satin, the ‘opaline’ lamps were exchanged for great gilded metal chandeliers; then the grandchildren wanted to make changes, they wanted to renovate, in tune with the latest fashion, mixing antiques with modern pieces, and the Louis Philippe divan went very well with the white-lacquered hammered iron modern lamps as did the walls in cementite and the two surrealist paintings. Once the whole house was moved to an elegant neighbourhood, to a more modern building, and it was then that Francisco ordered the great curtains of almond-green silk draped according to the latest French fashion, and the white baroque stucco: thus the house became somewhat ‘decadent’, as an ‘à la page’ architect said, but it was all right, it had style, it was much admired by friends and a fashionable magazine featured it.

I never thought it would wind up like this and, that morning, when our house no longer existed, I found a piece of veined white plaster and saw that it was a small chip from a rose-coloured lamp. But how strange, how very strange that there was nothing left of our lovely house, that there was nothing left to distinguish it from the others! It was all grey, all dust, just like all other grey mounds that had been houses, but certainly none as beautiful as ours had been.

Then the bombs mercilessly demolished the work of man, then we understood that the house should be for the ‘life’ of man, it should serve, it should console: and not show, as in a theatrical exhibition, the useless vanities of the human spirit: then it was that we understood why houses fell down, along with the stucco, the ‘mise en scène’, the satins, velvets, fringes and coats of arms. In Italy the houses fell down, along the Italian roads; in Europe the houses fell down. And for the first time men would have to rebuild the houses, so many houses in the centre of great cities, along the country roadways, in villages; and for the first time ‘man thought about Man’, about reconstructing for Man. The war destroyed the myths of ‘monuments’. In houses, too, there should no longer be monumental pieces of furniture. They too, in part, go to causing wars; furniture should ‘serve’, chairs are for sitting on, tables to eat from, armchairs are for reading and relaxing, beds are for sleeping; and so the house will no longer be an eternal and terrible home, but an ally to man, quick and docile, which can, like man, die.

In Europe reconstruction is going on and the houses are simple, bright, modest; for the first time in the world maybe man has learned and, in the morning after those nights of flame and over the rubble of his home, felt that the house is its dweller, is ‘himself’, and felt ashamed of his old house as if he had been publicly displaying his personal weakness and vices.[2]

1944. In a temporary professional studio, Milanese architects used to get together, hidden from the Salò police, to study the foundations of a new syndicate and professional organisation. This was the Associated Architect’s Organisation, later transformed into the Movimento Studi Architettura.

The years that should have been ones of sunshine, blue skies and happiness I spent underground, running and taking shelter from bombs and machine guns. The ‘love’ for the ‘underground men’ reached its climax in 1944 during the Nazi-fascist occupation of northern Italy. The Germans (perfect city planners, for the other side) launched a project for underground cities (to the end they thought they would win the race for the atomic bomb). Now the Nazi-fascists were underground, the traitors against life and humanity. Far better to defy fate and death on the terrace of some building, watching the fireworks display of searchlights and airplanes’ machine guns. One article I wrote, a criticism of urban architecture that appeared as an editorial in Domus, was honoured with the attention of the Gestapo. I escaped by a miracle … underground!

Every minute lived was another victory. In hiding, we would listen to the BBC broadcast from London, which opened its international broadcast every day with the first strains of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. I listened attentively to the news about the heroic resistance in Stalingrad ….

1945. The war ends. The hope of building instead of destroying gives everyone courage. Everything was in our hands: we of the Left and centre-Left were happy.

Shortly after the armistice, together with a reporter and a photographer, I conducted a newspaper survey in the areas affected by the war. We travelled all over Italy, collecting data. We felt that something had to be done to get architecture out of its dead end. We then began to think about a magazine or a newspaper that would be available to everyone and would emphasize the typical errors of the Italians… To take the architecture problem into the lives of everyone, so that everyone could arrive at his or her conclusion and decide on the house they should live in, the factory they should work in, the streets they should walk along.

Modern architects, the INTRANSIGENTS – that is, those who work in silence and see in the new architecture a way towards cleanliness and the salvation of humanity – should be depicted as are certain saints of the past, in armour and brandishing a flaming sword, the sword to give combat to the countless multitude of incompetents and ignoramuses that besets us with their false crystal, false gods, twisted god’s and lion’s paws, satin curtains, taffeta curtains, damask curtains, fringes and frills, large and small moors, stucco of all types, coats of arms without weapons, real or fake Baccarat chandeliers, quilting, matelassés, chinaware (especially chinaware), cords, paints green or almond, pink, ice-cream coloured, sugar candy white, sky blue, purple and violet, tassels and pom-poms.

Of course we have a great deal of respect for ancient objects, the real ones, and also for those in our homes, but as relics, which are sometimes put away in cupboards. But to violate an era by imposing upon it plaster and cardboard stuffed animals means to be unaware of the weary and painful progress of humanity, where incompetence, dilettantism and ignorance make it slide back kilometres for every centimetre it has managed to gain in its struggle to go forward.[3]

In Rome I met Bruno Zevi, a well-known architectural critic who had left Italy for racial reasons and returned with the American Fifth Army. He had returned to establish in Rome the Association for Organic Architecture. We then decided to start a weekly architecture magazine called La Cultura della Vita. It was printed in Milan by the same company that produced Domus. I was also invited to participate as an architectural critic in the daily paper Milano Sera and in the Congress for National Reconstruction.

1946. The old phantoms came back, the old names returned, and Christian Democracy came into power. Along with it, figures from past governments, all that we thought had been overthrown for ever.

I married P. M. Bardi, whom I had admired ever since I was a bobby-soxer at the Rome Artistic Lyceum. Pietro was important, modernist, promoted the arts, was the greatest Italian journalist. We dated, and then married. That same year we travelled to South America, already familiar to Pietro.

Arrival in Rio de Janeiro by ship in October. Dazzled. To those who arrived by sea, the Education and Health Ministry building advanced like a great white and blue ship against the sky.[4] The first message of peace after the flood of the Second World War. I felt myself in an unimaginable country, where everything was possible. I felt happy, and Rio was not in ruins.

What is Brazil like for a European arriving for the first time in Rio de Janeiro? Viewed from an airplane, the contrast between slums and modern constructions suggests social chaos rather than bourgeois resentment for standardised skyscrapers in the place of stylish houses.

Viewed from a ship, Copacabana Beach and the bay with the Ministry of Education and other buildings appear suddenly, almost leaning against the forest, and emanate a scent that comes on board, suggesting a human effort that has no time to ponder whether the skyscraper is better than the little folkloric Portuguese house.

Background documentation: the Museum of Modern Art’s book Brazil Builds, a real, almost daily hope, not metaphysical in the simplicity of the architectural solutions, in the human ‘hellos’, things unknown for a generation which arrived from very far away. At that time, right after the war, it was like a lighthouse shining over a field of death…. It was something marvellous.

Reception in the Rio branch of the IAB (Brazilian Architect’s Institute): Lúcio Costa, Oscar Niemeyer, Rocha Miranda, the Robertos, Athos Bulcão, Burle Marx and others. In Cosme Velho, Portinari, the sculptor Landucci, Marcos Jaimovitch, old friends of Oscar. This was the first international vanguard of Brazil (the second was to be Brasília). Dazzle of intelligent simplicity and personal capacities. Dazzle of an unimaginable country with no middle class, just two great aristocracies: that of the land, of coffee, of sugar cane, and … the People.

1947. Chateaubriand invites Pietro to found and run an art museum in Brazil; either in Rio or in São Paulo. I much preferred Rio, but the money was in São Paulo. I told Pietro that I wanted to stay, that I had re-encountered the hopes of the nights during the war. Thus we remained in Brazil.

1951. I became a naturalized Brazilian citizen. When one is born, one chooses nothing, one just happens to be born. I was not born here, but I chose to live in this country. For that reason, Brazil is my country twice over; it is my ‘country of choice’ and I feel like a citizen of all its cities, from Cariri to the Minas Gerais Triangle, the cities in the countryside and on its borders.

Notes

- This ‘Literary biography’ is a collage, compiled from several texts written by Lina Bo Bardi taken from the book Lina Bo Bardi by Instituto Bardi Casa de Vidro. The English translation has been slightly modified by the catalogue editors.

- Lina Bo Bardi, ‘Na Europa a casa do homem ruiu’ (In Europe the House of Man Fell Down), in Rio, no. 92 (February 1947): 53-55.

- Lina Bo Bardi, ‘Uma cadeira de grumixaba e tabôe é mais moral do que um divã de babados’ (A chair of grumichama and boards is more moral than a divan of frills), interview in Diário de São Paulo, 13 November 1949.

- The Education and Health Ministry building (1938-43) is a landmark of modernist Brazilian architecture.

– Niall Hobhouse