Superstudio: In Yesterday’s Tomorrow

‘Metamorphoses become frequent when a culture does not have sufficient courage to commit suicide (to eliminate itself) and has no clear alternatives to offer either‘

– Adolfo Natalini

Following social and economic upheaval, there is often a retreat to the home. Traditionally, the ‘home’ is identified with a site of settlement and reconciliation, where wild things – and radical ideas – become domesticated. In the aftermath of the political upheavals and disillusionment of 1968, the Museum of Modern Art in New York opened its seminal exhibition about domestic design entitled Italy: The New Domestic Landscape. Curated by the Argentinian architect Emilio Ambasz, the exhibition explored the global concerns of industrial societies through a survey of the previous decade in Italian design. It recognised domestic design as fundamentally reactionary, which, for a short while, became the main site of resistance and critique for many radical Italian designers.

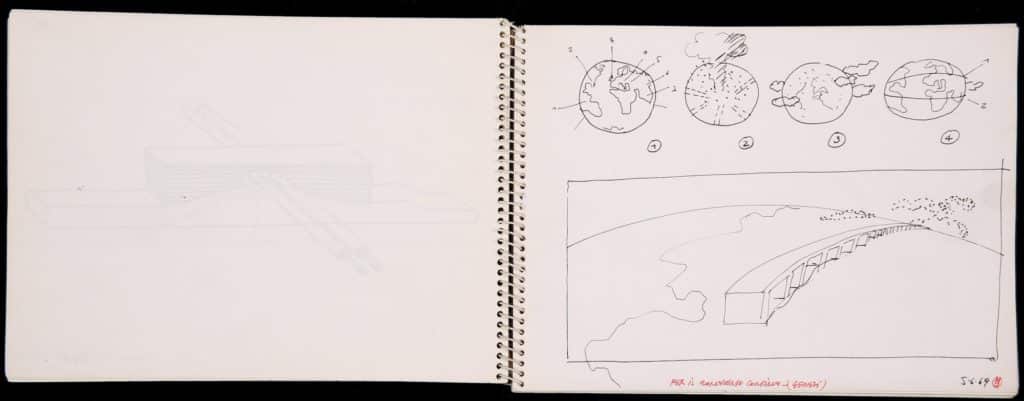

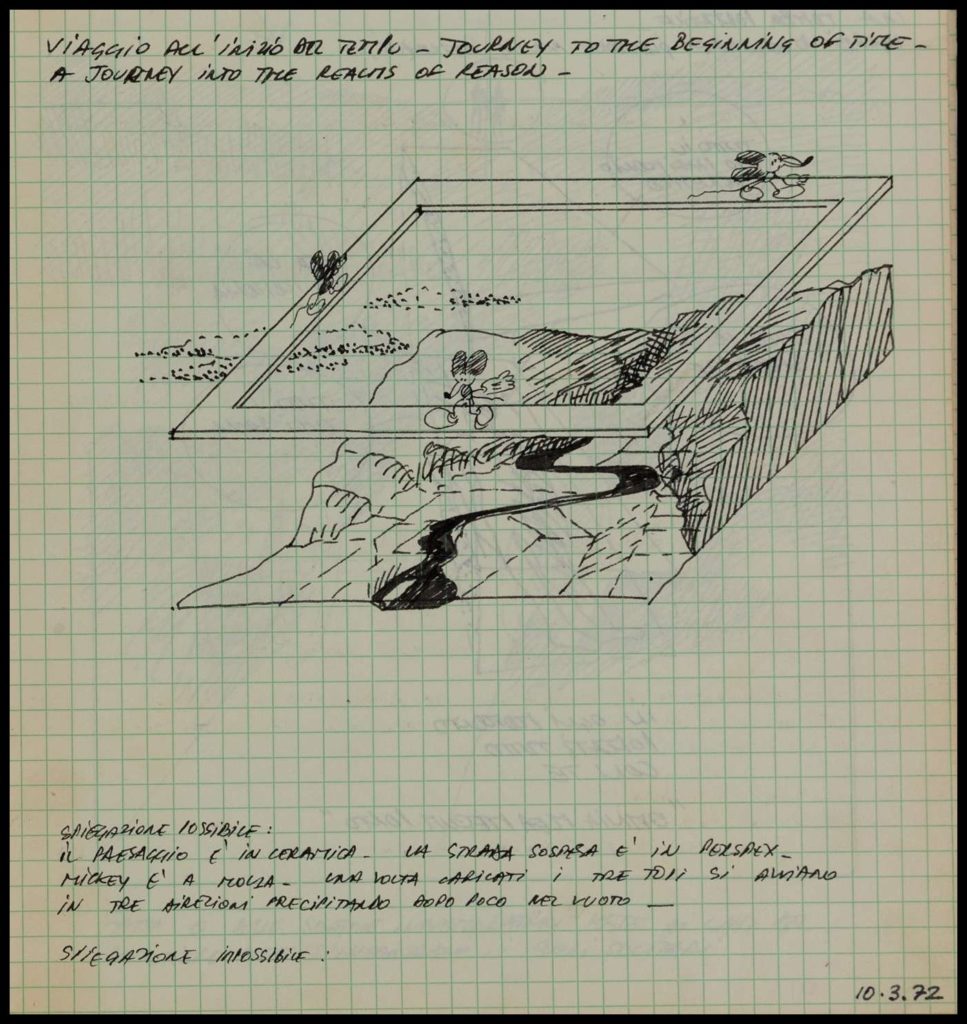

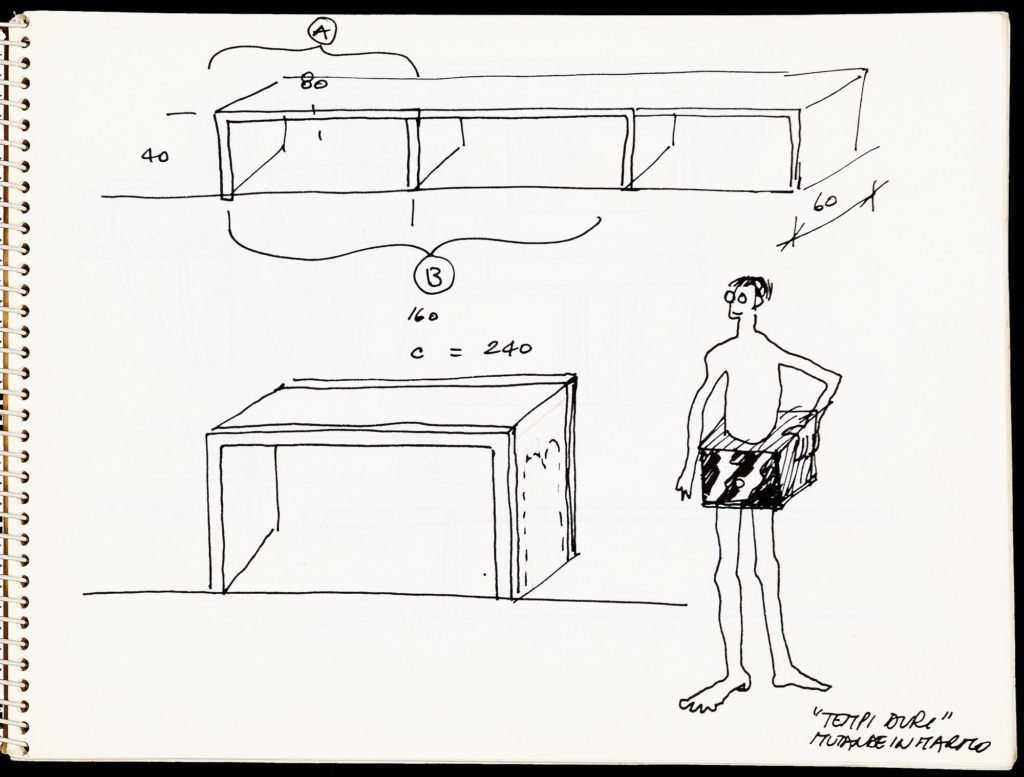

The newly commissioned environments of the exhibition included an installation by the Florence-based Superstudio: a box of infinity mirrors with a geometric grid on the floor and clouds projected on the ceiling, and an animated film. ‘Life: Supersurface’ outlined the designers’ proposition for an alternative model of life on Earth, exploring its possibilities without objects and work. The sketchbooks of one of the founders of the radical collective, Adolfo Natalini, narrate the evolution of thought behind this project, and many others that preceded and followed it, beginning with the early drawings of the Continuous Monument, the Twelve Ideal Cities, the Measurement series, as well as initial sketches for Fundamental Acts that included ‘Life: Supersurface’. Natalini described his drawings as imprints and maps of the future, travel plans and magic calendars: explorations of the territories of the will and hope, and testimonies to the lives never lived.

For Natalini, drawing became an attitude. He studied art before turning to architecture, and described himself as ‘an artist by soul and architect by profession’. His drawings – like the films and collages of Superstudio – were not to be realised, but complete in themselves. They were an exploration into an expanded territory of architecture; tools of liberation and, at the same time, resistance to an architecture that could not free itself from its disciplinary conventions, and thus remained powerless in the face of much needed social and political change.

Superstudio’s concept of ‘anti-design’ would have meant the destruction of the object, the refusal of conventional building process, and with it, the elimination of all hierarchical power systems that man-made environments and objects have ever implied. The Florentine group suggested a new kind of architecture for a new, egalitarian society freed from hierarchies, possessions and any form of labour. This radical political statement was first made explicit in their Continuous Monument, which would have replaced the man-made environment with a non-hierarchical grid structure wrapped around the Earth as a continuous, globalising belt. A symbolic and unifying architectural gesture, it was in Natalini’s own words, ‘a single piece of architecture to be extended over the whole world’.

While Natalini’s drawings reveal his intrigue with American pop-culture, they are often also compared with the dystopian images of Florence’s flood in 1966, the year when Superstudio was founded. This flood was the worst natural disaster in the history of Natalini’s adopted city (he was born in Pistoia); the Arno River washed away possessions and temporarily erased most central areas of the city. While doubtless that Superstudio’s collages must have called to mind memories of the recent flood – and, in turn, rendered a near future of negative utopia – Natalini claimed that the drawings were simply an exercise in restoration, recovering the Pleistocene epoch when Florence was a lake. He joked about the potential economic and touristic aspect of such proposal: ‘Florence would be a submerged city, which would be perfect for tourism. They could see the city by submarine instead of a bus!’

The sardonic humour of Superstudio’s projects, and Natalini’s early drawings are testimony to a time when modernist architecture was in crisis and the future no longer thinkable without warning and irony. As Natalini pointed out, radical architecture ceased to exist at the very moment its name was coined, yet Superstudio’s warning seems more relevant today than ever. Looking back at these proposals from the late 60s and early 70s, one cannot help but wonder if our networked contemporary lifestyles, mobility and new behaviours dictated by a post-ownership society, have fulfilled a version of Superstudio’s negative techno utopias.

Echoing Natalini’s thoughts about the crisis of a culture that is unable to reinvent itself, the Home Futures exhibition at the Design Museum brings together visions of yesterday’s tomorrows and reveals long-forgotten versions of our contemporary time, as a way of reflection and warning. It compares today’s realities with past futures of the twentieth century, and, while referring back to those fantastical – and yet eerily familiar – visions, it asks: do we live in yesterday’s tomorrow? Are we fulfilling future predictions or, rather, are we just stuck in the past? What does our nostalgia for past futures reveal about our present time?

Home Futures is curated by Eszter Steierhoffer and is on view at the Design Museum in London until 24 March 2019.