Les Fantasmes de l’origine: A Reverse Archaeology of the Désert de Retz

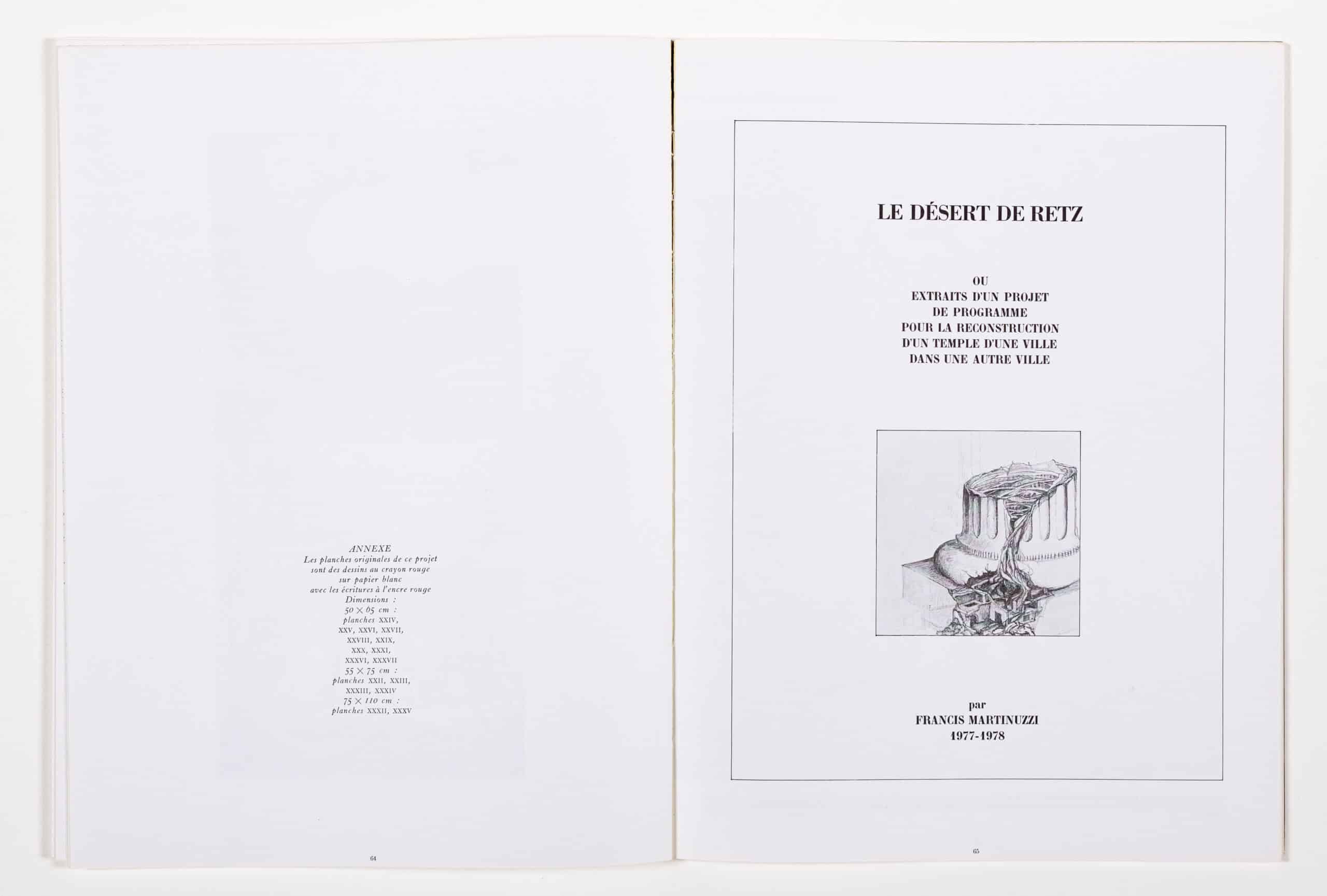

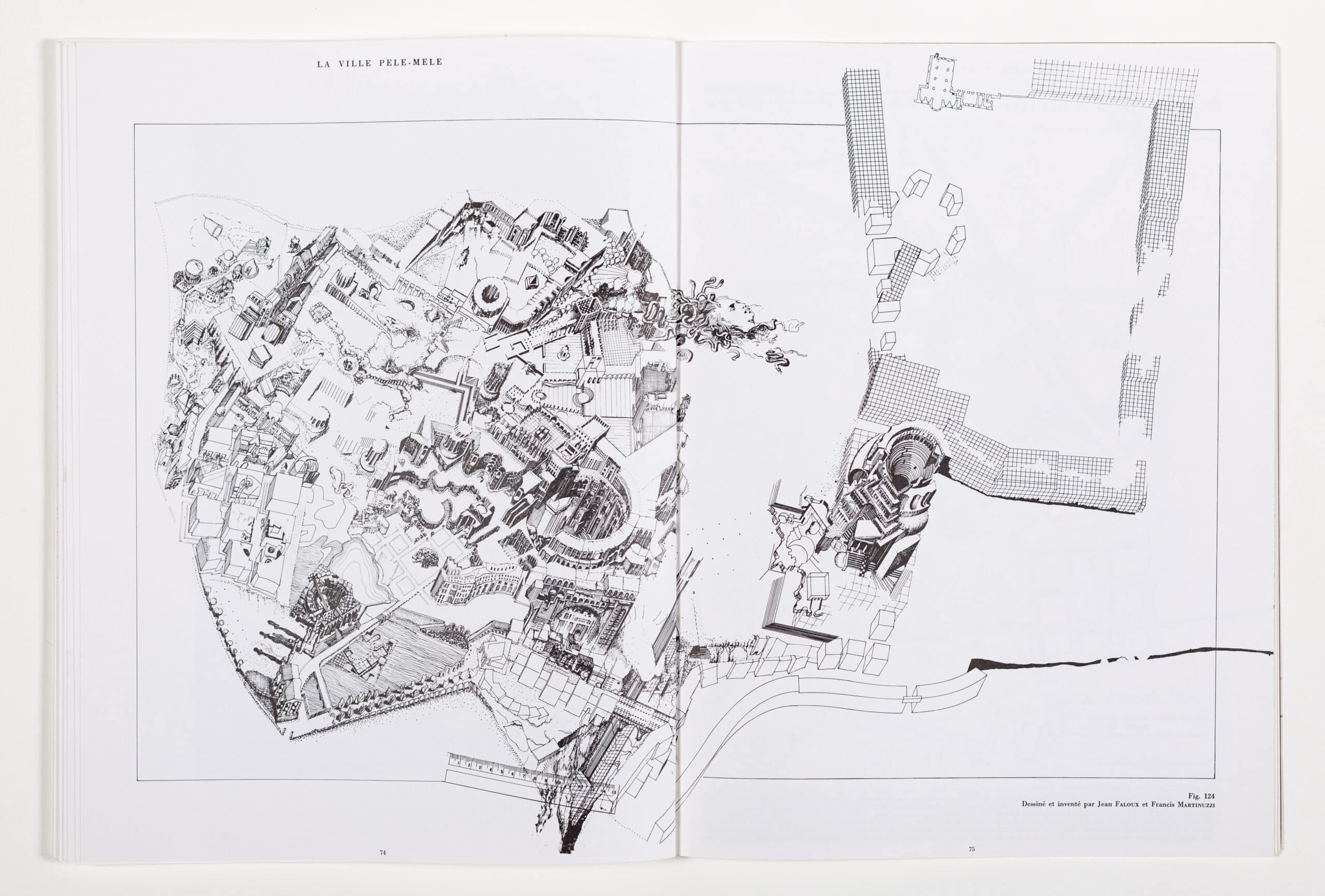

Last year, Francis Martinuzzi contacted Drawing Matter after seeing a reproduction of one of his drawings on our website. The drawing was from a project from the submission for his architectural diploma with Jean Faloux under the tutelage of Antoine Grumbach at Unité Pédagogiuqe no. 6 (L’École nationale supérieure d’architecture de Paris-La Villette) in 1976. The project is a reversed archaeology of the Désert de Retz—the landscape garden conceived and built by the aristocrat François Racine de Monville on his estate on the edge of the forêt de Marly from 1774.

In 1978, Martinuzzi’s project was published in the second issue of the French radical architecture magazine L’Ivre de Pierres, edited by Jean-Paul Jungman of Aerolande. Drawing Matter offers here an English version of that presentation, translated by Jane Yeoman. The post is further illustrated with two drawings and sketchbook pages from the Drawing Matter Collection.

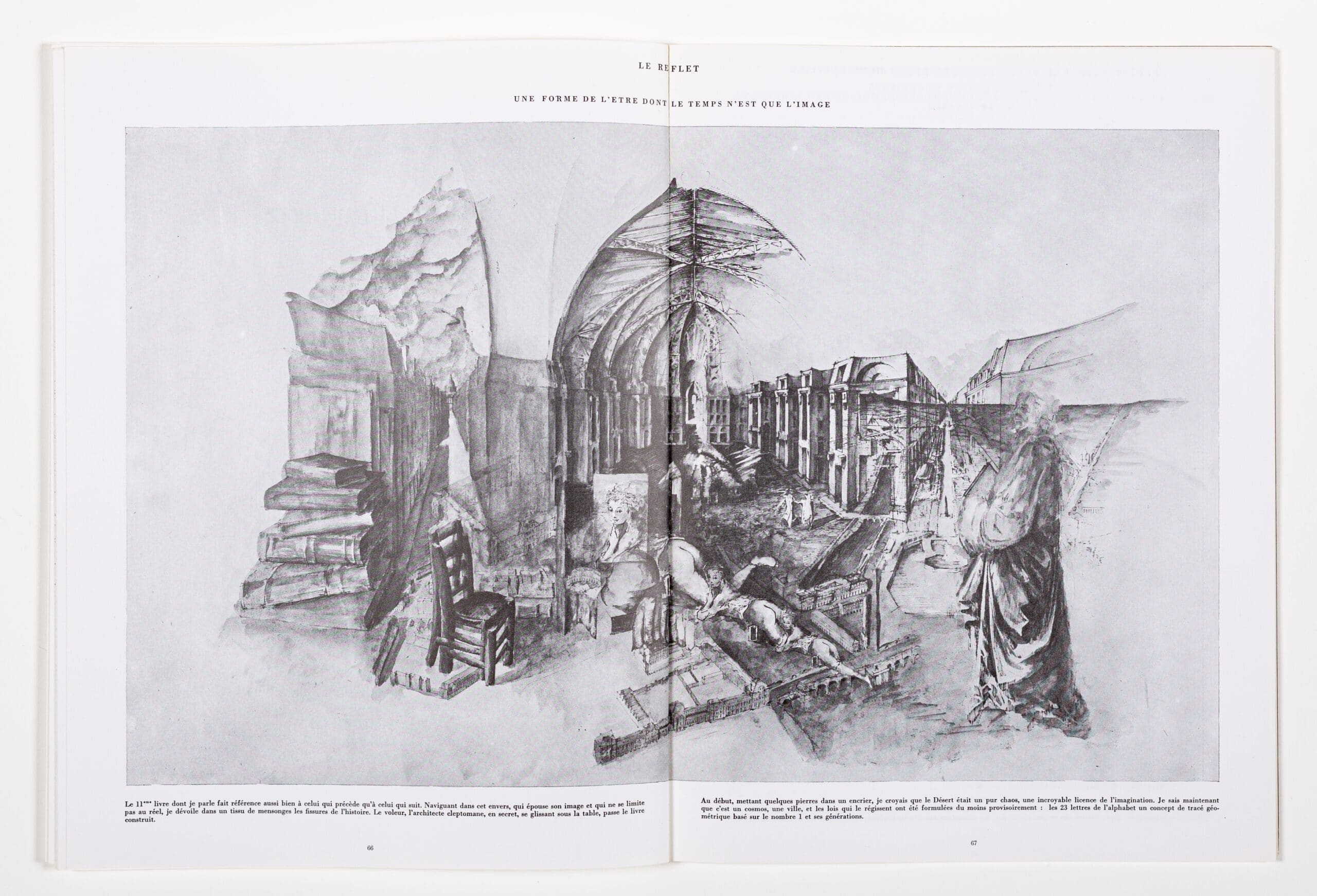

A FORM OF BEING OF WHICH TIME IS MERELY THE IMAGE

The 11th book of which I speak refers as much to the one that precedes it as to the one that follows. Navigating on the other side, which embraces its image and is not limited to reality, I uncover the cracks of history within a tissue of lies. The thief, the kleptomaniac architect, in secret, slipping under the table, hands over the constructed book.

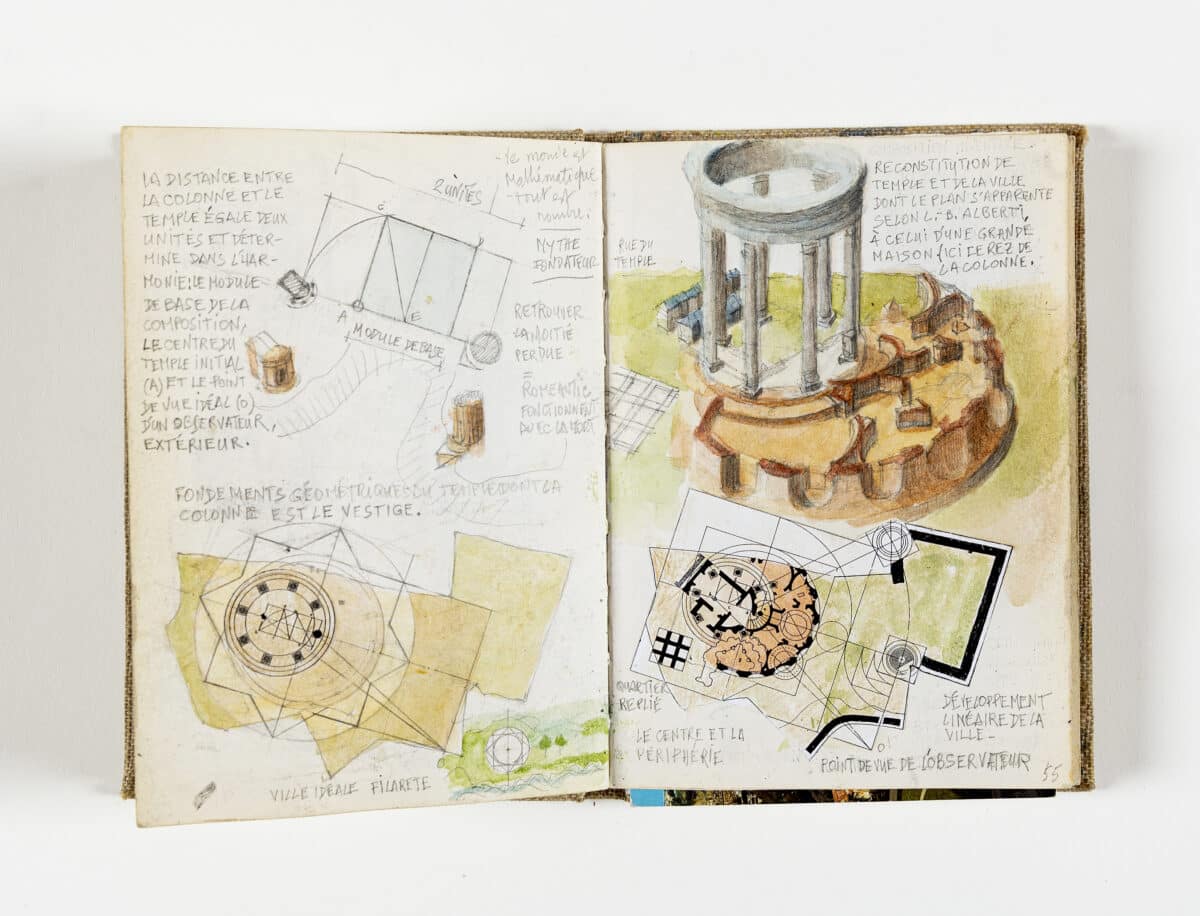

At first, placing a few stones in an inkwell, I believed that the Désert was pure chaos —an extraordinary license of imagination. I now know that it is a cosmos, a city—and the laws that govern it have been formulated at least provisionally: the 23 letters of the alphabet, a concept of geometric tracing based on the number 1 and its generations.

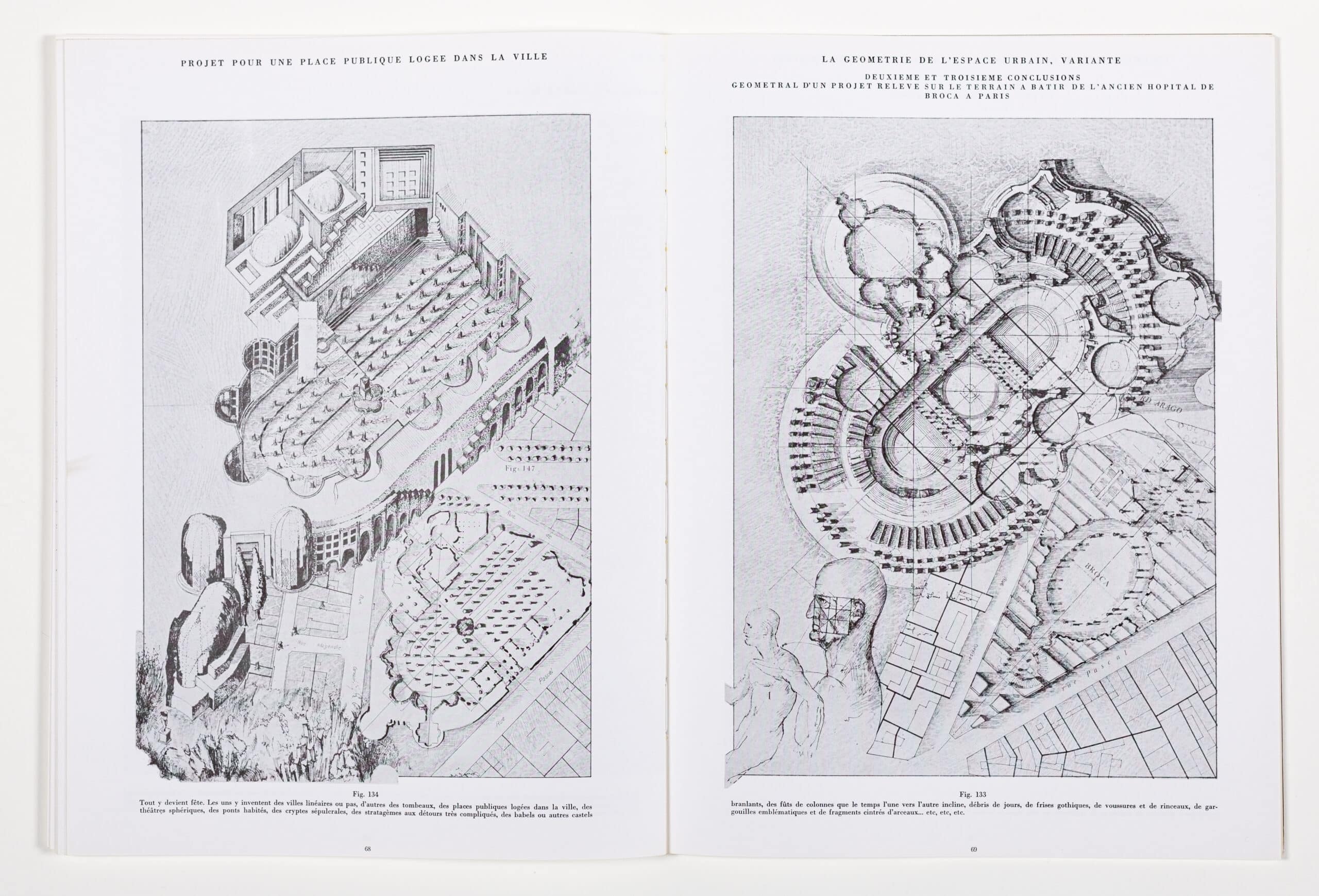

THE GEOMETRY OF URBAN SPACE, VARIANT

SECOND AND THIRD GEOMETRIC CONCLUSIONS OF A PROJECT LAID OUT ON THE BUILDING SITE OF THE FORMER BROCA HOSPITAL IN PARIS

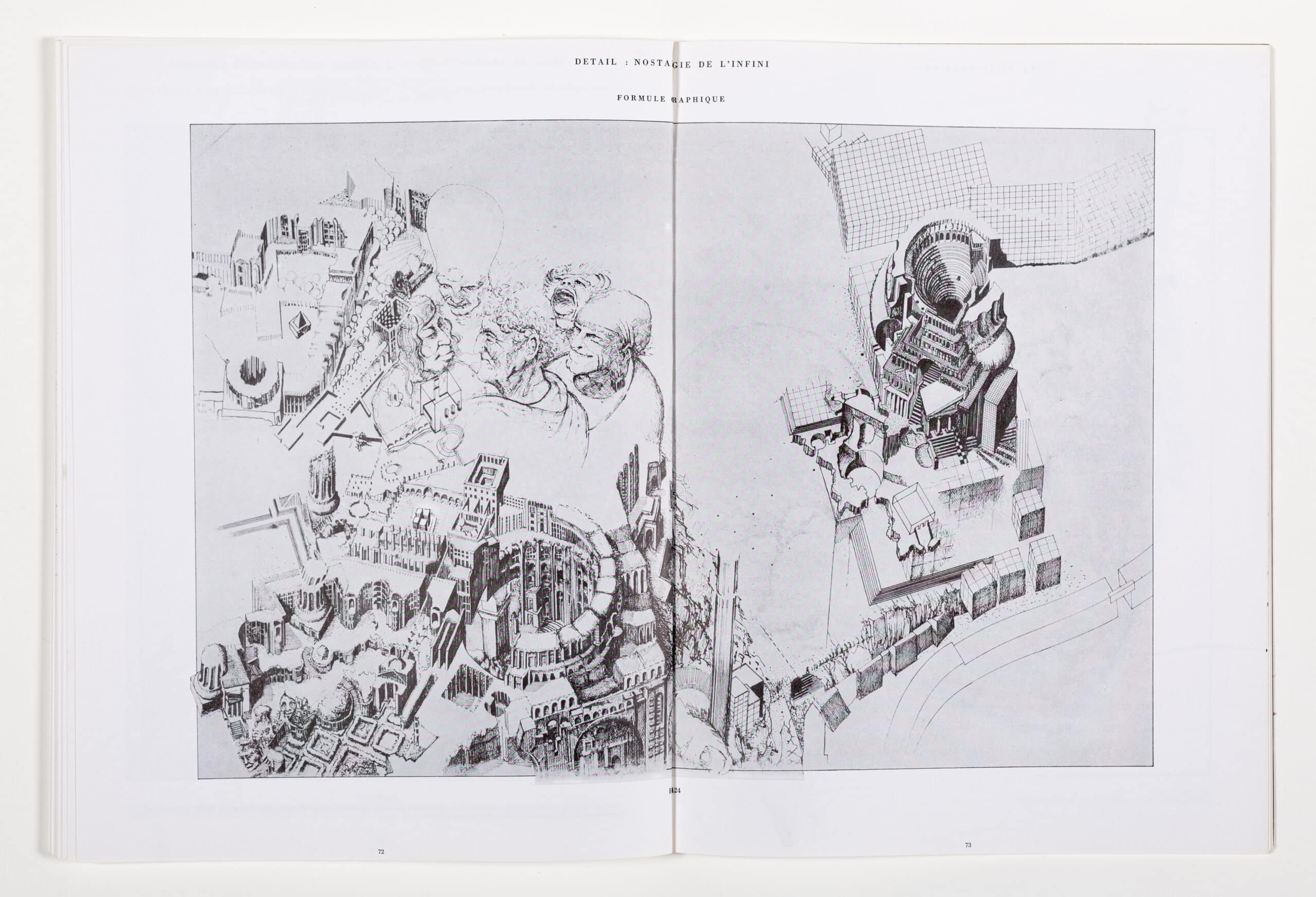

Everything becomes a celebration. Some invent cities, either linear or non-linear, others invent tombs, public squares set within the city, spherical theatres, inhabited bridges, sepulchral crypts, stratagems with highly complicated detours, Babels or other small rickety castles, shafts of columns that time inclines the one towards the other, fragments of days, Gothic friezes, archivolts and foliage, emblematic gargoyles and vaulted fragments of arches, etc., etc., etc.

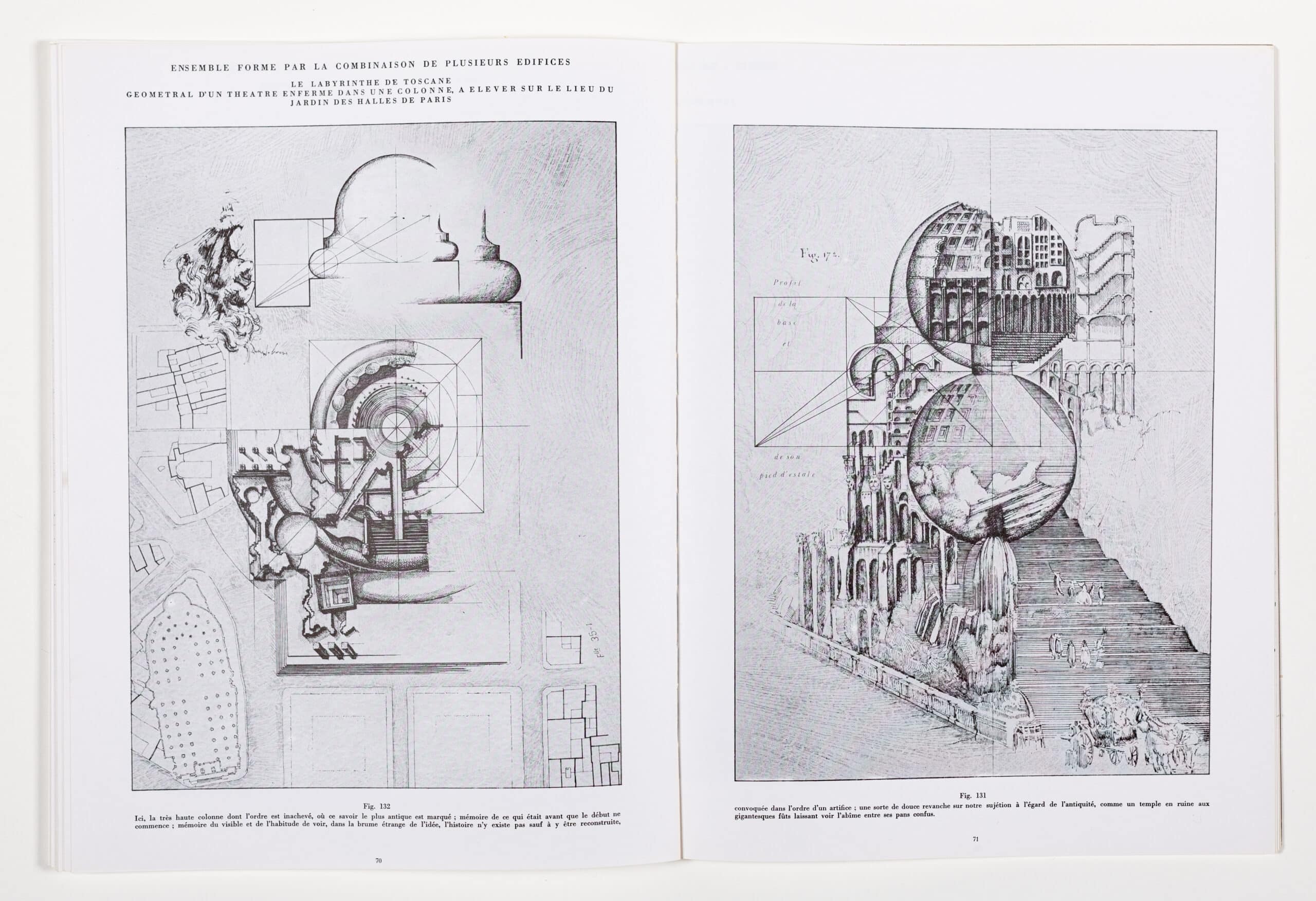

THE TUSCAN LABYRINTH

GEOMETRAL OF A THEATRE ENCLOSED IN A COLUMN, TO BE BUILT ON THE SITE OF THE JARDIN DES HALLES IN PARIS

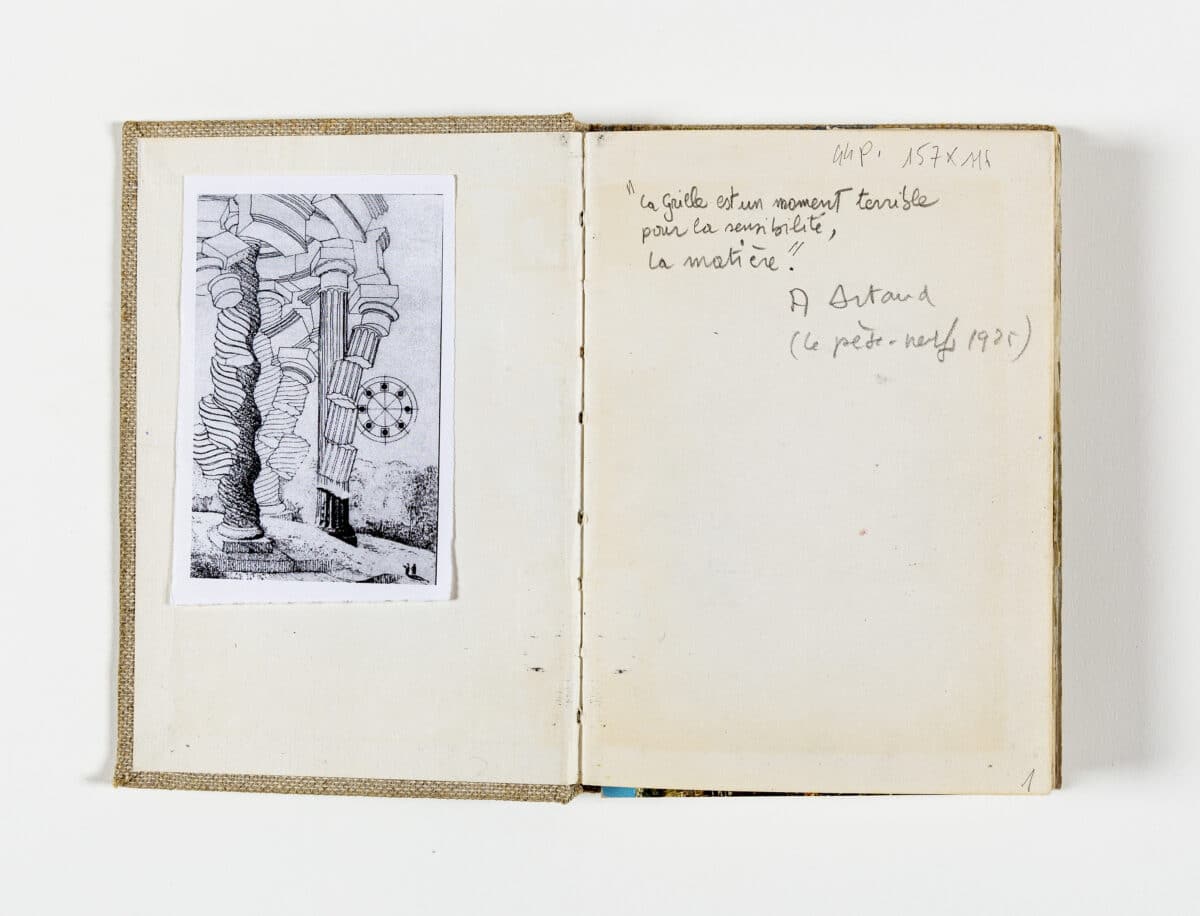

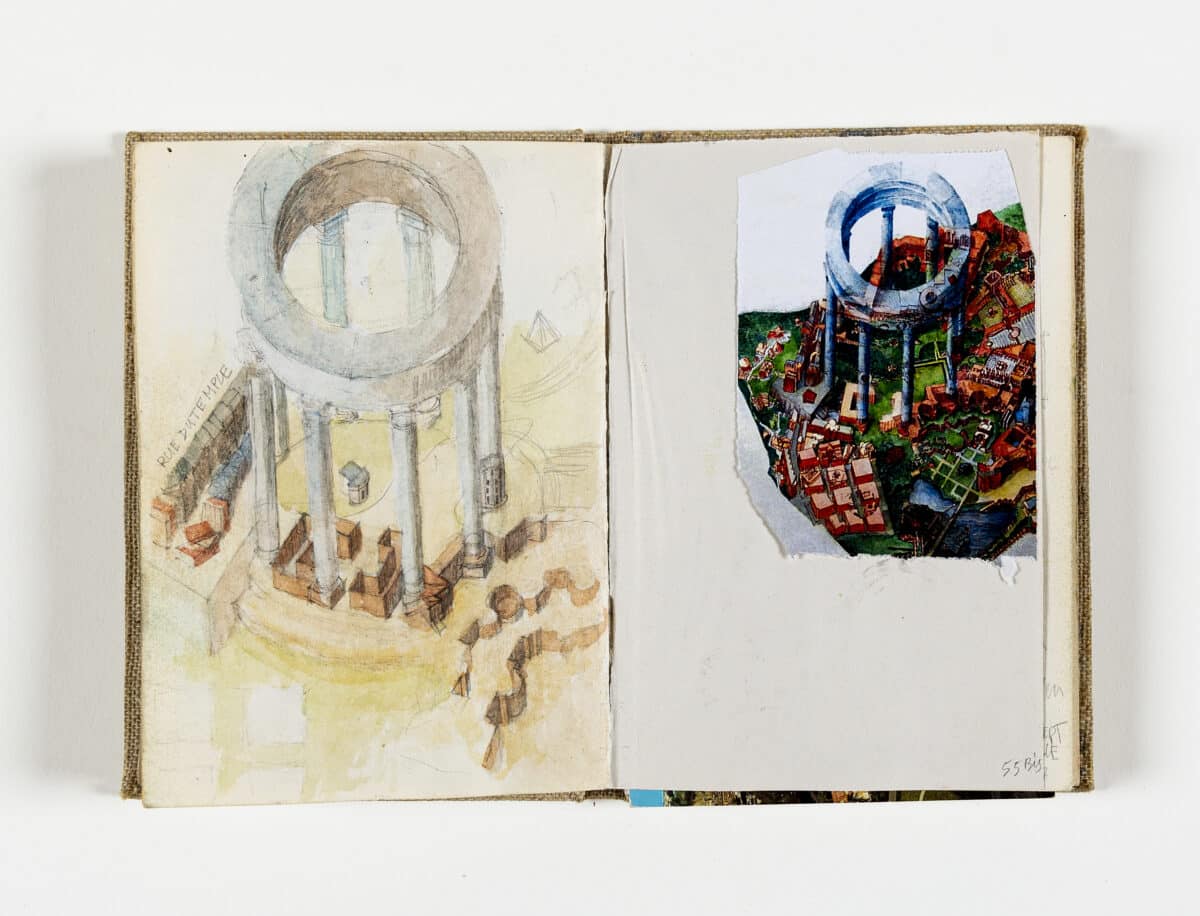

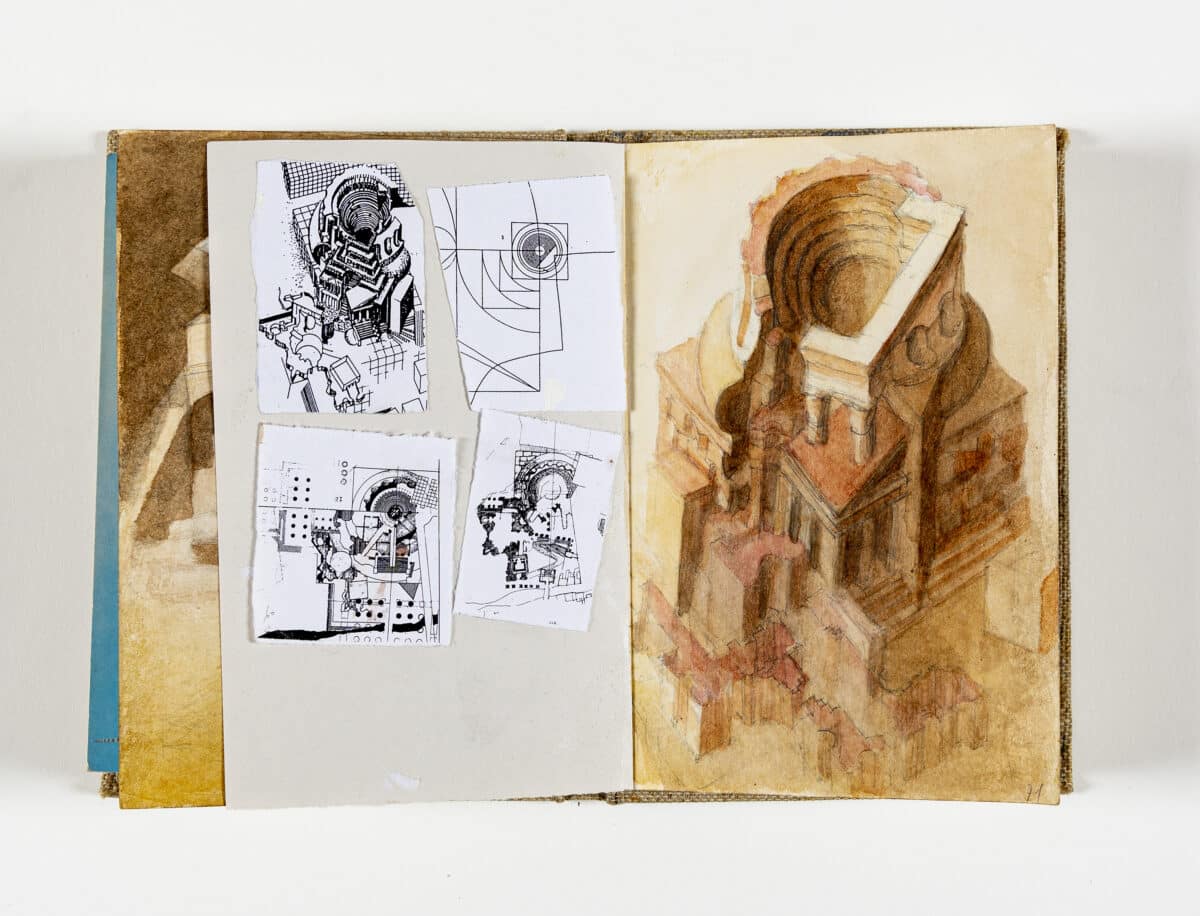

Here, the extremely tall column with unfinished order, where the most ancient knowledge is pronounced; memory of what was before the beginning had begun; memory of the visible and the experience of seeing, in the strange mists of the idea, history which does not exist there unless it is reconstructed, summoned in the order of an artifice; a kind of sweet revenge over our subjection with respect to antiquity, like a temple in ruins with gigantic shafts revealing the abyss between its chaotic sides.

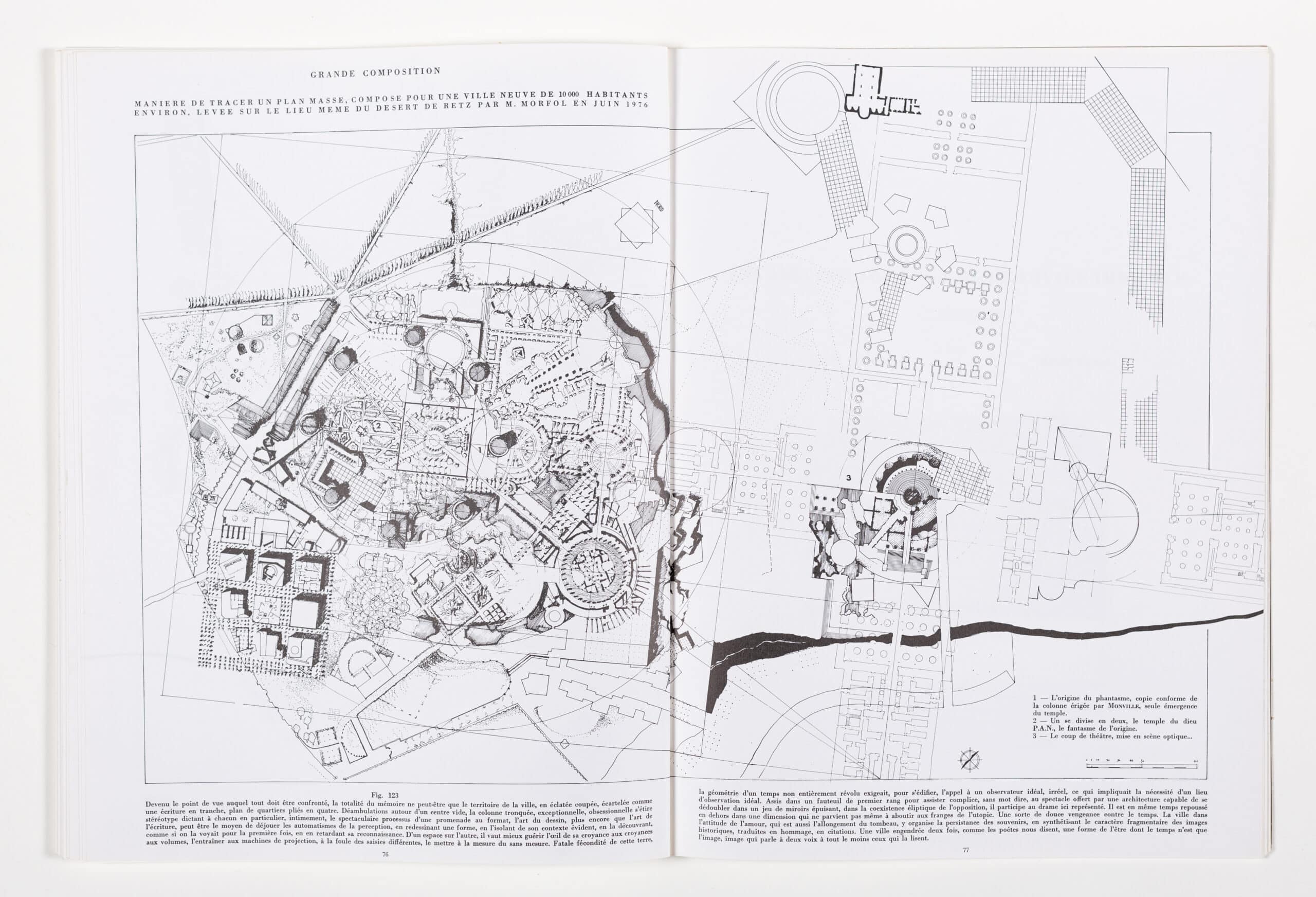

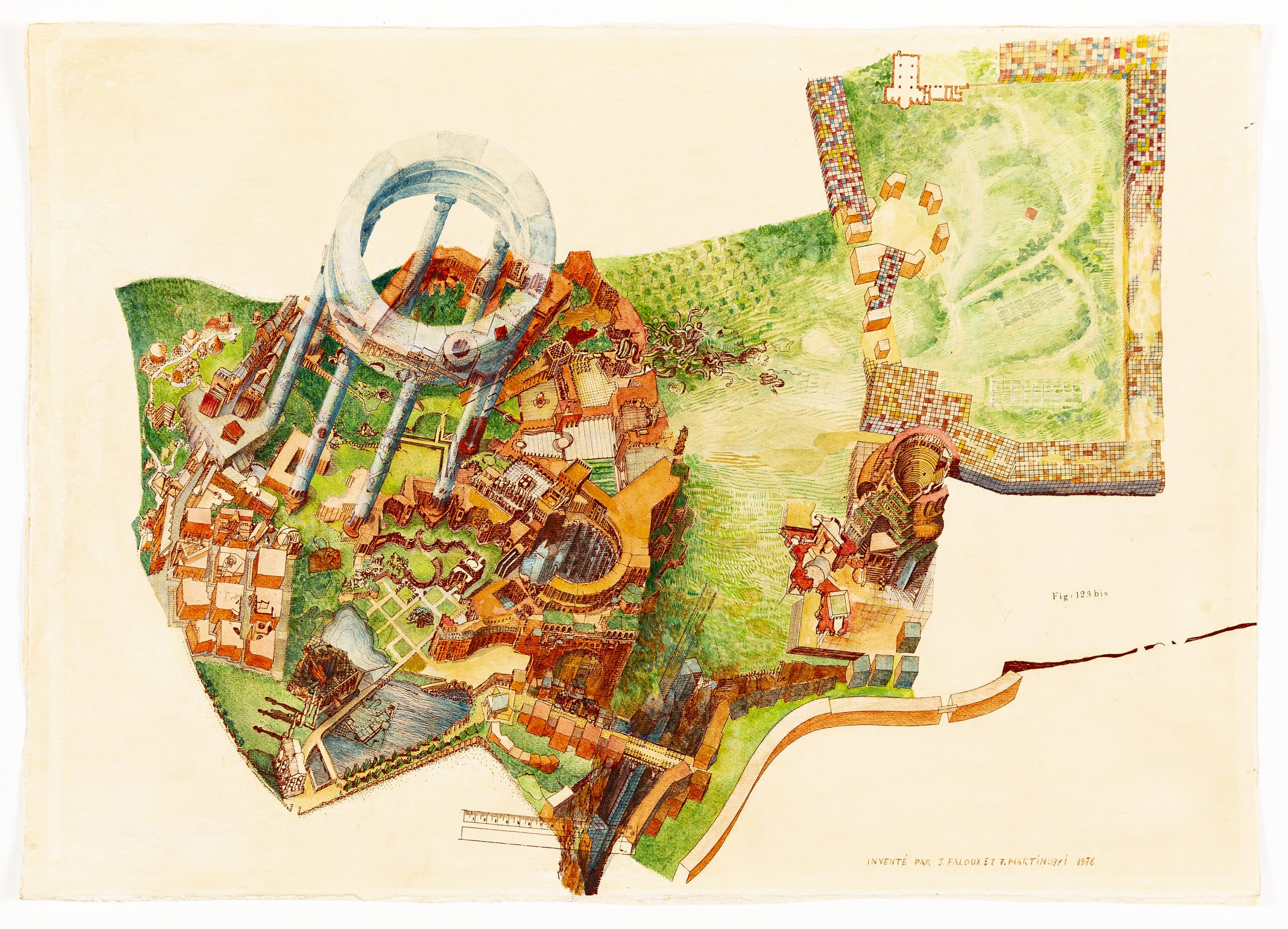

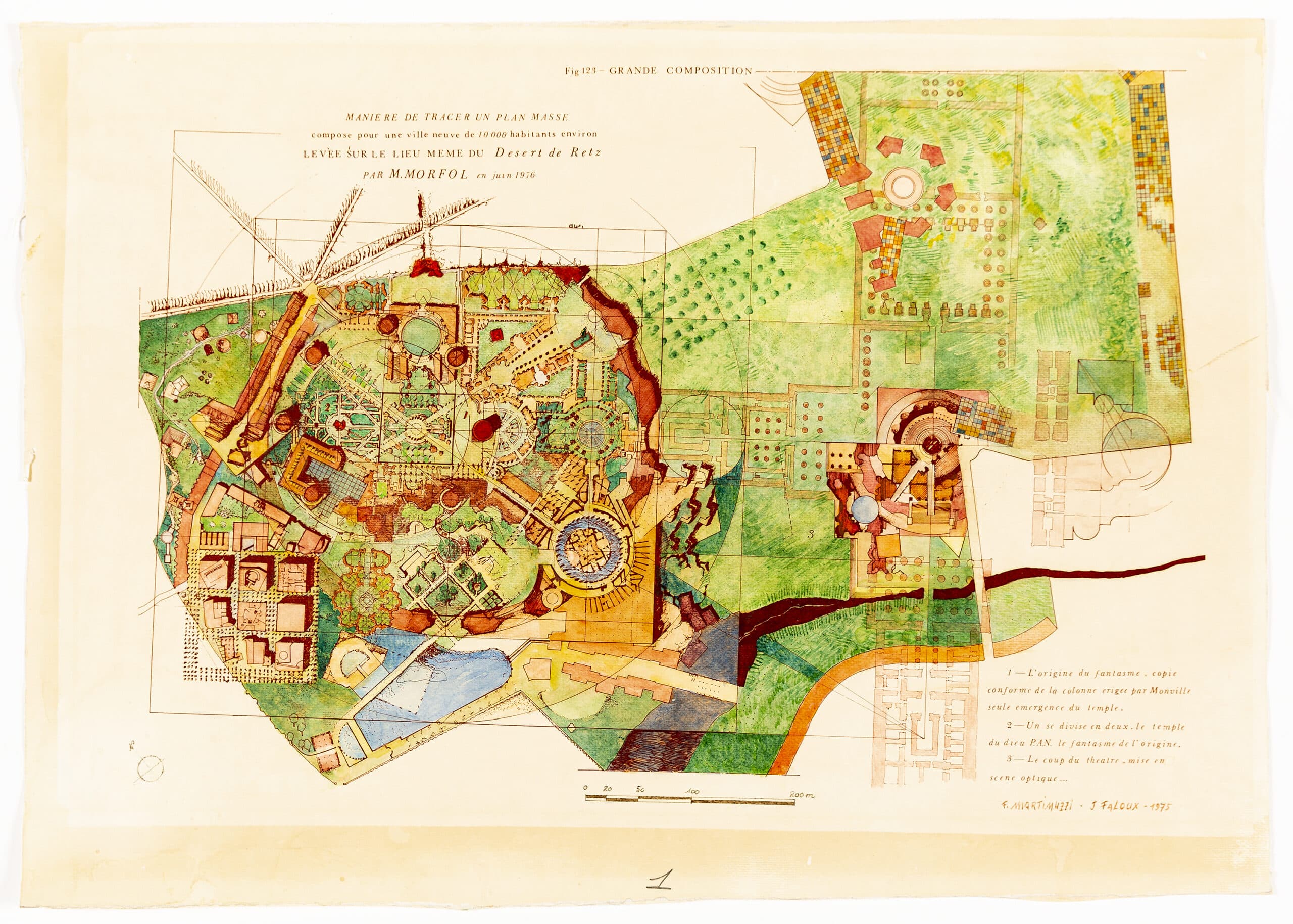

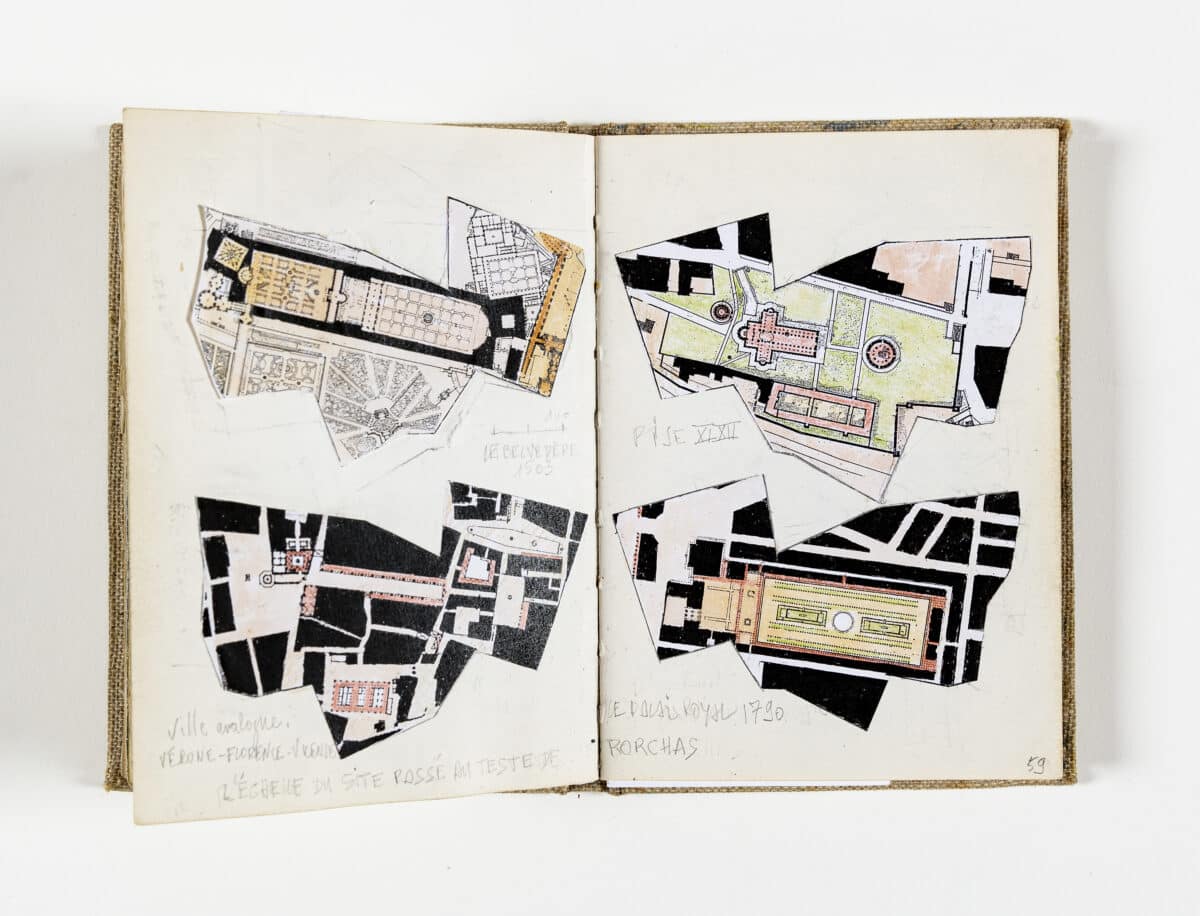

A WAY OF DRAWING A MASS PLAN, CREATED FOR A NEW TOWN OF APPROXIMATELY 10,000 INHABITANTS, SURVEYED ON THE SITE OF THE DESERT DE RETZ BY M. MORFOL IN JUNE 1976

Having become the point of view with which all must be confronted, the entire memory can be nothing but the area of the city, in exploded fragments, broken up like a composition in slices, a map of districts folded into four. Wanderings around an empty centre, the truncated column—exceptional, obsessive—stretches the stereotype, intimately dictating to each one in particular, the spectacular process of a walk in format—‘the art of drawing, even more than the art of writing, presents the way to thwart the automatisms of perception, by redrawing a form, in isolating it from its obvious context, in discovering it, as if seeing it for the first time, by delaying its recognition.’[1] From one space to another, it is better to cure the eye of its belief to a belief in volumes, to train it towards projection machines, to the multitude of different takes, to put it in the measure of the measureless. Fatal fecundity of this earth, the geometry of a time not entirely bygone required, so as to construct, the appeal to an ideal, hypothetical observer, which involved the need for an ideal place of observation. Seated in the front row to complicity witness, without saying a word, the show offered by an architecture capable of folding itself up in an exhausting game of mirrors, in the elliptical coexistence of the opposition, the observer participates in the drama given here. At the same time, he is pushed outside into a dimension that does not even reach the fringes of utopia. A kind of sweet revenge over time. The city in the attitude of love, which is also an extension of the tomb, arranges therein the continuity of memories, by synthesizing the fragmentary nature of historical images, translated as a tribute, in quotations. A city twice begotten, as the poets tell us— a form of being where time is but the image— an image that speaks in two voices, at least to those who listen.

[1] Quoted from Maximo Scolari’s text in Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, Issue 9, April 1977, 90.

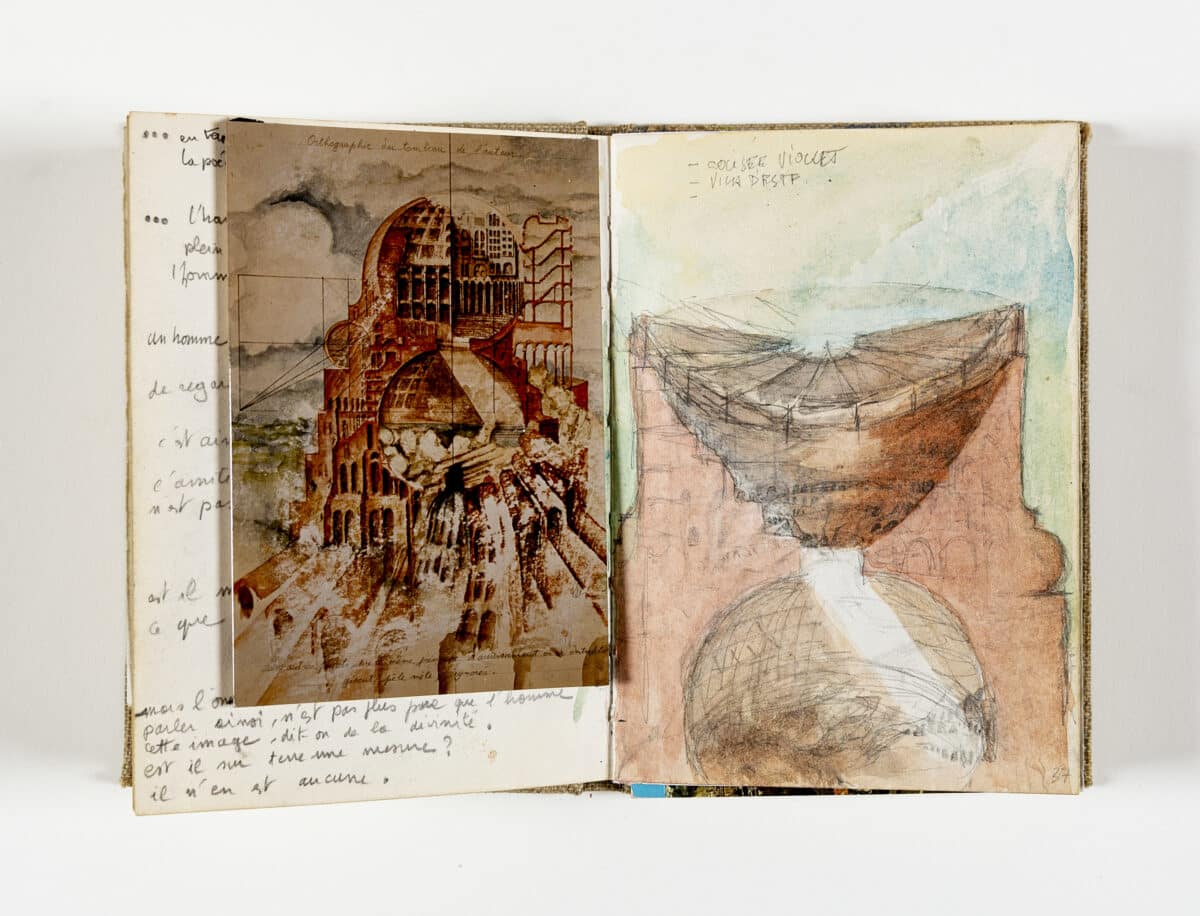

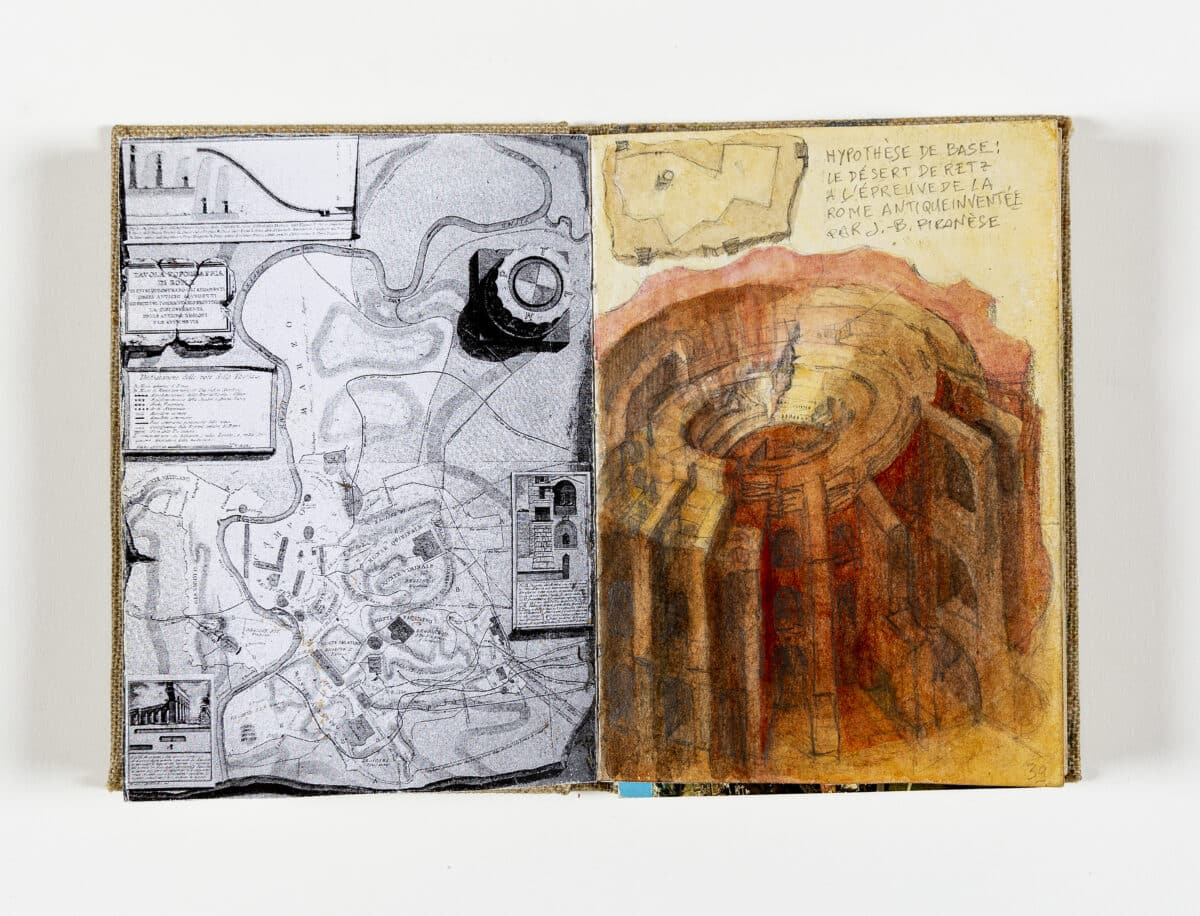

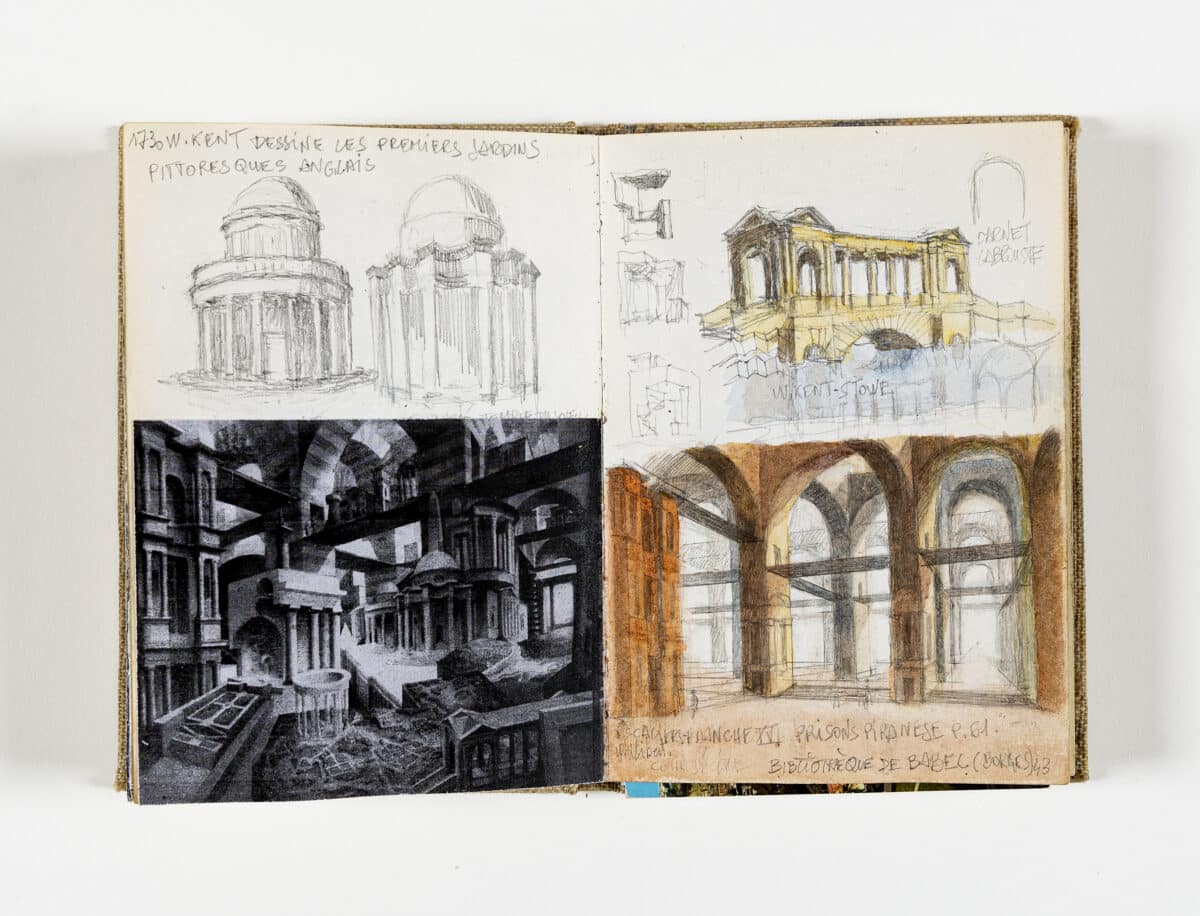

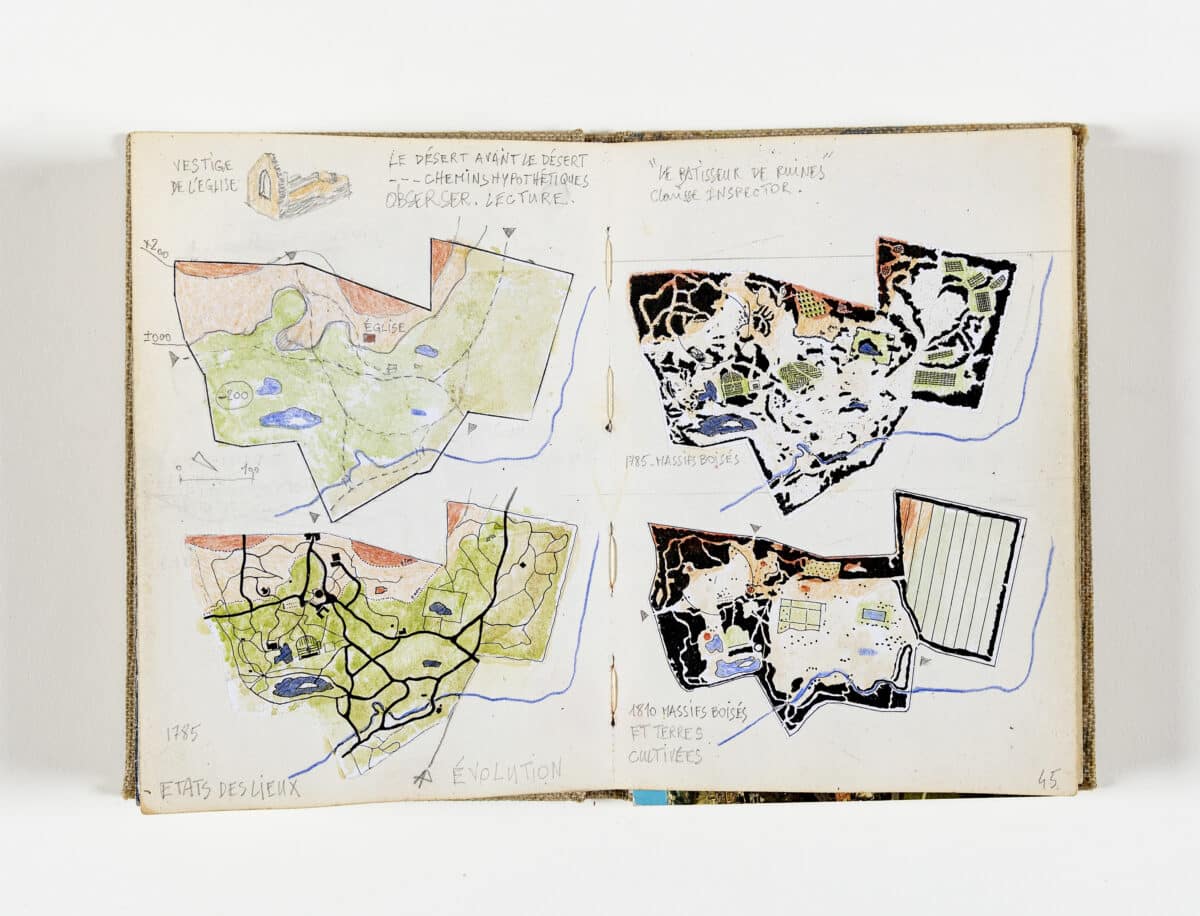

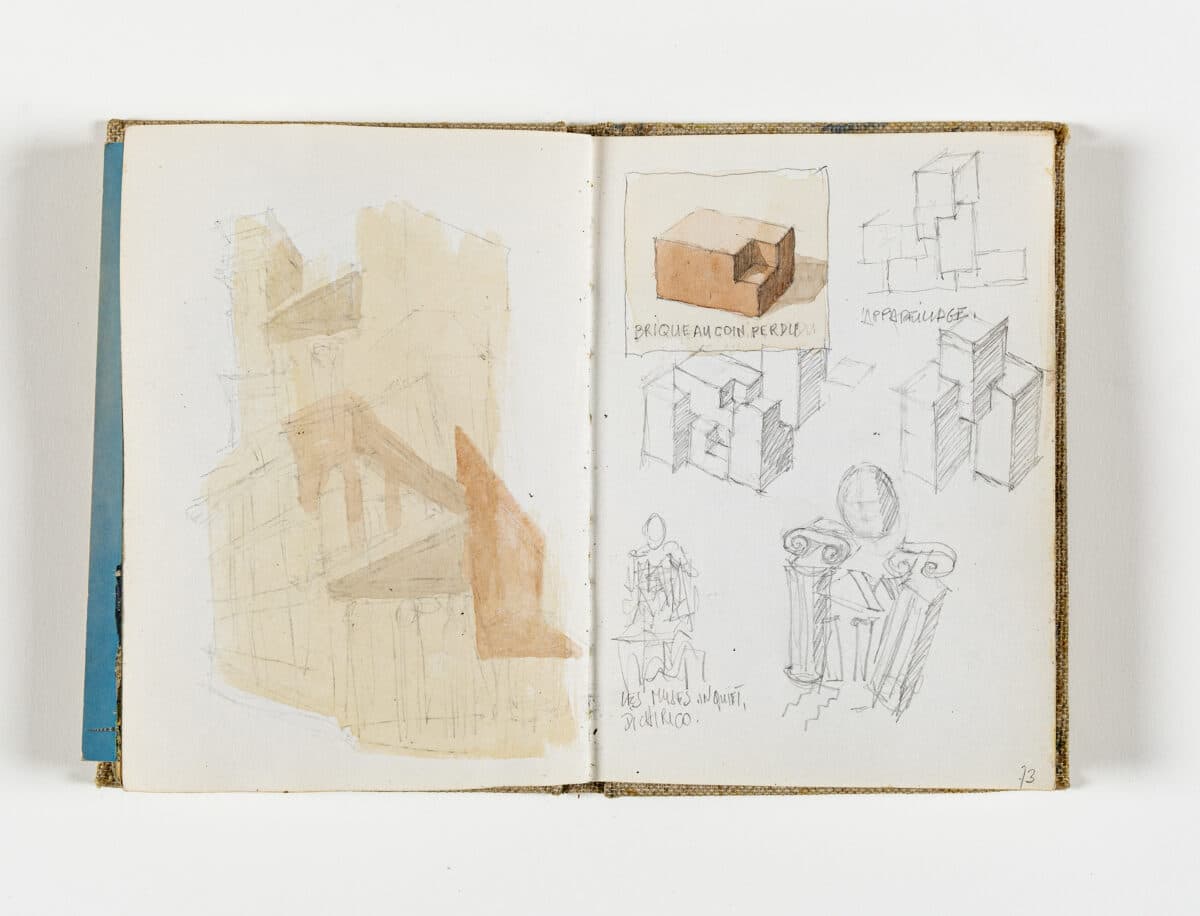

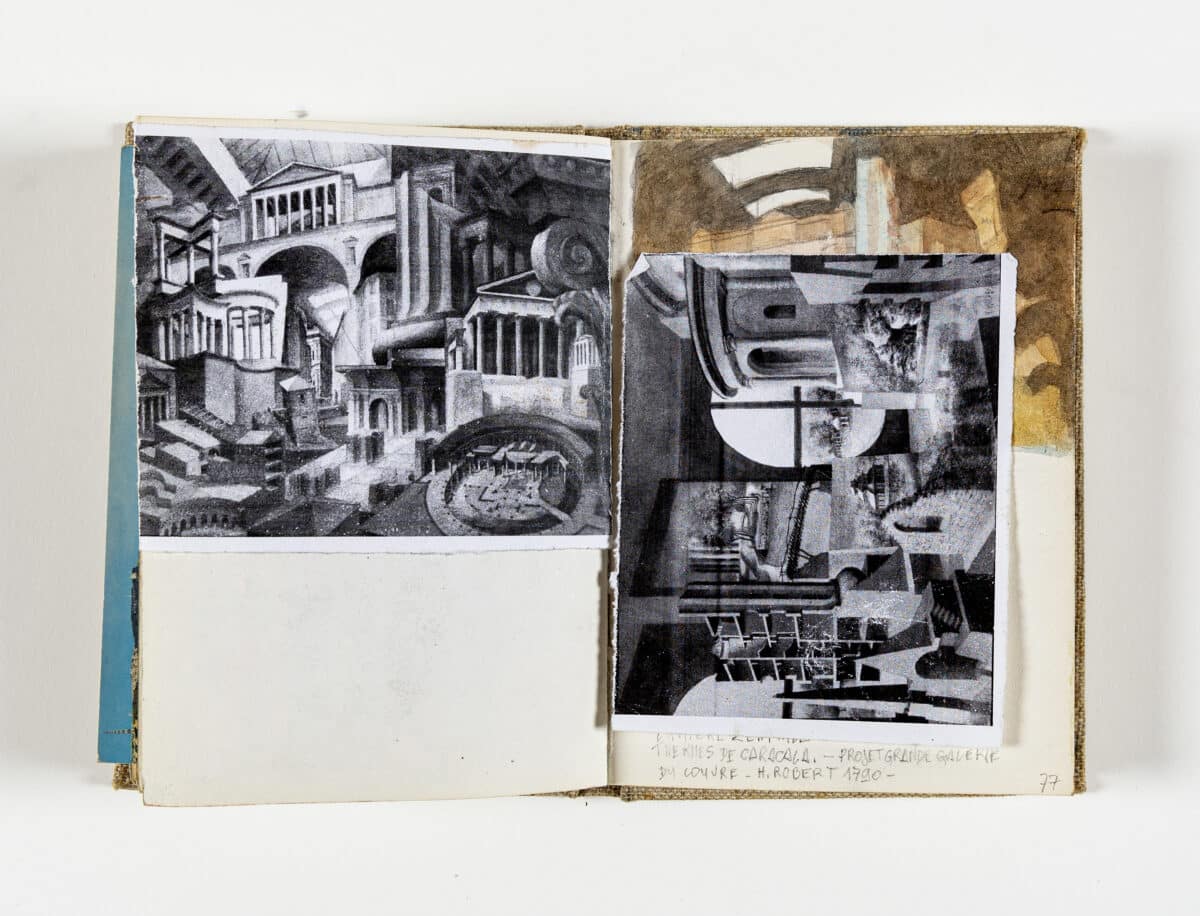

The following images are from Francis Martinuzzi’s Clothbound Sennelier sketchbook (44 pages). Diploma project with Jean Faloux, under Antoine Grumbach, Unité Pédagogique no. 6, Le Désert de Retz, Chambourcy, 1976. Pencil, watercolour, collage, 165 × 115 × 25 mm. DMC 2949.1.

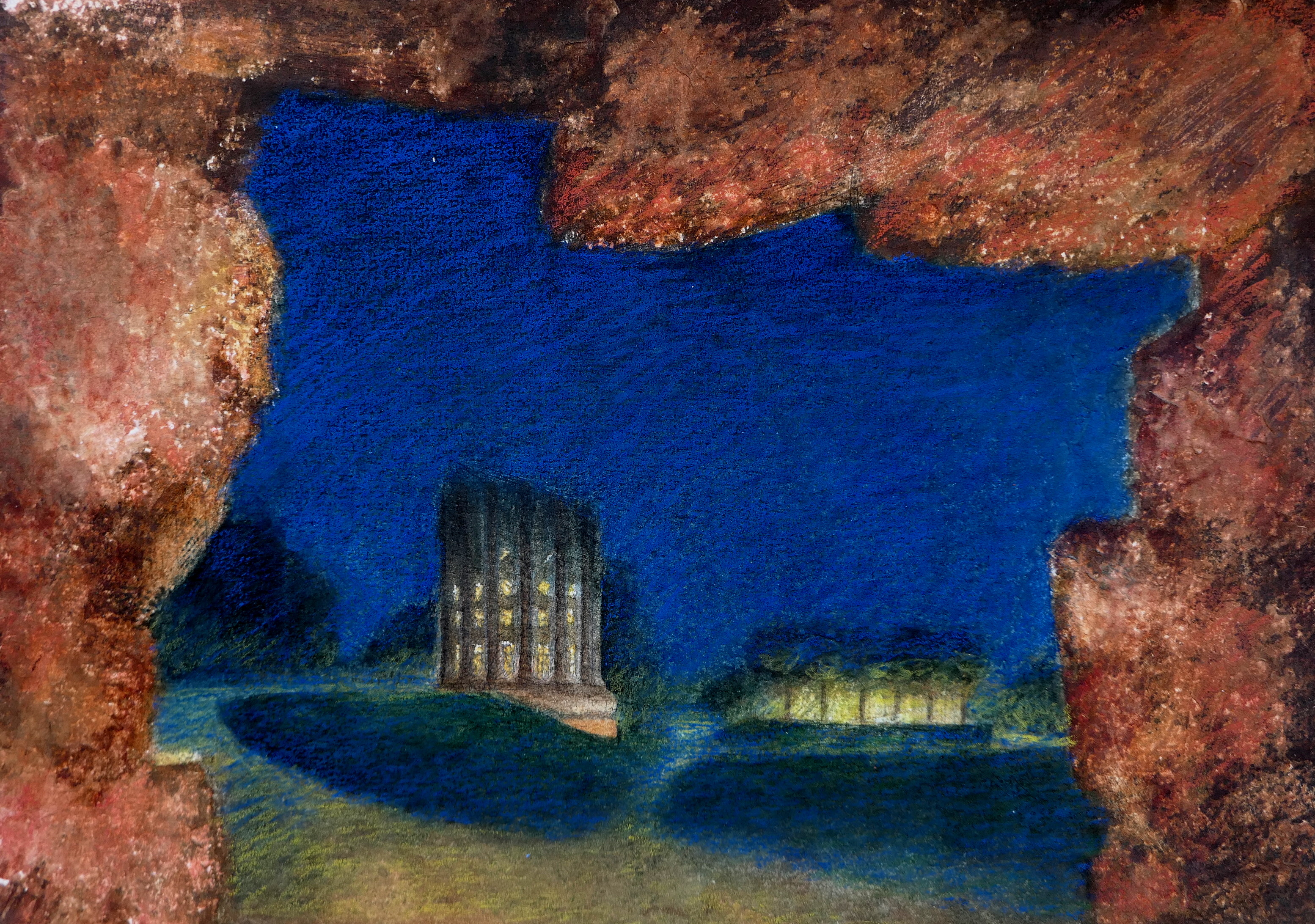

In 2024, Francis revisited his 1976 Désert de Retz project, producing a new set of watercolours of the different views in the garden.

Francis Martinuzzi (born in 1949) is an architect, who worked in the Taller de Arquitectura Ricardo Bofill between 1976 and 1980. He built social housing in Algeria in the 1980s, and exhibited his watercolour work in Centre Pompidou in Paris, DAM in Frankfurt, and Fondation de l’architecture in Brussels, organised by Jean Dethier (1987–1988). From 1996 until 2021 Francis taught ‘Representation of Architecture’ at the School of Architecture of Saint-Etienne (ENSASE).