Tracing Shadows: A Workshop Primer

Here, Mark Dorrian examines the theoretical history of the shadow and its evolving role in architectural drawing. The text acts as a word-and-image primer for the third colloquium event, jointly hosted by the RIBA and V&A Drawings Collections, and Drawing Matter, which will take place later this month—a day of conversations, gathered around original drawings and photographs, in which participants examine intensely the presence (and absence) of shadows in the representation of architecture.

*

Ideas of both drawing and measurement are closely involved with the cultural history of the shadow—at least, as it has been imagined in the West. Indeed, the shadow might appear to be the primal form of drawing, and even an early species and intimation of photography. Every historical account of shadow thinking is obliged to go via the story of the daughter of Butades the potter, recounted in Pliny’s Natural History, who, by tracing the outline of the shadow of a young man cast by lamplight on a wall, fixes his image.[1] In this way, she makes a representation of a representation. Already in this story we recognise the complex relation of presence and absence that the shadow puts into play. In the tale, it mediates between the living presence of the man and his absence (and, by implication, death) that is to come—the shadow comes to be both the index of his presence and the thing that enables its trace to remain upon his departure.

Point-like light sources, like lamps and candles, produce radial rays, expanding shadows beyond the dimensions of the bodies that cast them. Their geometry can be understood as the same as that of linear perspective, an observation made by Leonardo when in diagrams he depicted a shadow-casting candle as a kind of extramissive eye. Sunlight, on the other hand, due to the great distance to the source, results in an orthographic shadow projection as its rays are virtually parallel. Shadows projected onto a plane at right angles to the rays will therefore retain the dimensions of the things that cast them. As Alberti observed, ‘the light of stars makes shadows exactly the same size as bodies, while the shadows from fire are larger than bodies’.[2] Robin Evans, writing of Karl Friedrich Schinkel’s rendering of the shadow-tracing origin myth of drawing, remarks on how it shows an exterior scene with a sun-projected shadow—the architect not only shows the discovery of drawing as necessarily prior to the constructed building that will depend on it, but also illustrates orthographic projection in its originary form.[3] When the Spanish Jesuit J.B. Villalpando wanted to describe ichnography (the plan, from ichnos, ‘footprint’), he characterised it not as an imprint formed by pressure upon the ground but rather a shadow cast by parallel rays of light passing vertically through a diaphanous structure.[4]

Early thinking on shadows was more clearly marked in astronomy than in works concerned with art and architecture. In this, the shadow was closely tied to geometry and measurement. The Islamic polymath Alhazan (Ibn al-Haytham) was reputed to have written a treatise on ‘the instruments of shadows’.[5] In another ancient origin scene, Thales of Miletus was said to have determined the height of pyramids by waiting until the time of day when the length of a man’s shadow was equal to his height and then measuring theirs. In his commentary on this story, the philosopher of science Michel Serres argues that this is a parable of geometry’s suspension of time through the motif of the stopping of the sun in the heavens (the moment of measurement requiring its position to be fixed).[6]

What do depicted shadows do? An illusionistic wall painting at the Villa of the Mysteries in Pompeii shows projecting sculpted cornice brackets rendered perspectively in relation to a central viewing point. Their shadows are also rendered, although curiously their projection also switches direction when they pass the viewing point. It is as if they move to accommodate the representation of the perspectival splay of the projecting brackets, behind which, to the right-hand side, the shadows would otherwise be hidden. Perhaps the concern here is less with producing a naturalistic rendering of the fall of the shadow than with an understanding of the shadow as a double of the form, which lets us see the latter better. The effect is similar in the ‘unswept hall’ mosaic removed from a villa on the Aventine Hill and held in the Vatican’s Museo Profano. It shows a floor littered with debris, perhaps the remains of a meal, with strangely mobile shadows that project in different directions. The classicist James Davidson has suggested that the relative detachment of some items from their shadow may indicate that they are depicted falling and have yet to reach the ground.[7]

Perhaps most obviously shadows endow what is depicted with presence and substance. The effect of relievo was central to Leonardo’s concern with shadows—how to achieve subtle qualities of depth and massing upon a flat surface. In the Purgatorio, Dante notices that Virgil casts no shadow. His guide explains that when he left his material body in the tomb his shadow was interred with it. Here shadow is on the side of the corporeal and transient world and hence also with death. And yet we find that even luminous and deathless bodies may cause shadows. In Botticelli’s Annunciation (1489-90), the kneeling angel casts a shadow deep into the pictorial space. Perhaps it acts as a confirmation of the earthly presence of the divine messenger in the scene before the Virgin—his shadow extends toward her and her body seems to bend around it.

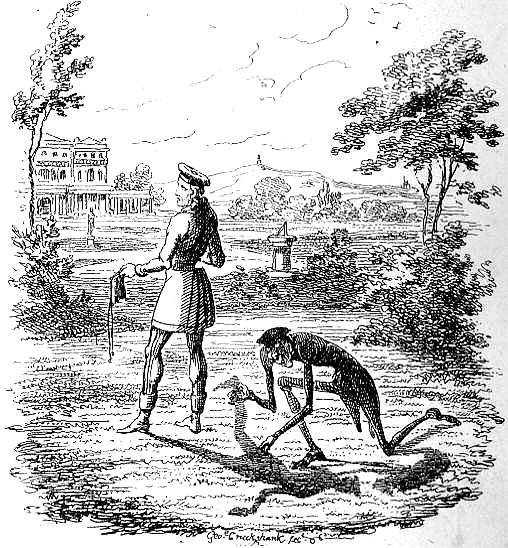

Associations of the shadow with the soul or spirit are ancient. Hades was populated with the shades of those who had once lived and the countenance of the god who enjoyed dominion over it was covered by a cap that, according to Hesiod, ‘contains the gloomy shadows of Night’.[8] Virgil’s astral body might have cast no shadow, but being shadowless could also be the mark of unexalted states, a portentous sign of defective or compromised presence. In the famous tale of Peter Schlemihl, written by Adelbert von Chamisso and published in 1814, the young man sells his shadow for a purse of gold that will never be empty. The buyer, a strange grey man, rolls it up and carries it off. It is of course a representation of Peter’s soul and when he, weary of insubstantial (shadowless) life, tries to redeem it, he is told it can only be returned on forfeit of his soul when he dies.

George Cruikshank (1792–1878), Illustration for Frontispiece to Adelbert von Chamisso’s Peter Schlemihl, 1861.

Throughout the 16th and 17th centuries attention to skiagraphy, the projection of shadows, became more pronounced in art and architecture, and its procedures increasingly codified. Vignola’s Regola delli cinque ordini d’architettura (1562) attended not only to the forms of the orders but to the drawing of the shadows that they cast. Descriptions of skiagraphic methods to depict shadows had appeared in works on perspective by Dürer and, later, Guidobaldo del Monte, and through the 17th century the inquiry was extended in treatises by Pietro Accolti (1625), Jean Dubreuil (1642), Abraham Bosse (1648) and others. The study of shadow projection would in due course go on to form its own particular and distinct genre of perspective treatise.[9]

Étienne-Louis Boullée, walking on the edge of woodland in moonlight experienced an epiphany that led him to the conception of an ‘architecture of shadows’, which he proclaimed in his manuscript, Architecture, Essai sur l’art (c.1790 but unpublished until 1953)—‘my own artistic discovery [and] a new road that I have opened’.[10] Boullée perceived a strange detachment of his own shadow, which together with the trees appeared, as he put it, ‘etched’ upon the ground. ‘The mass of objects stood out in black against the extreme wanness of the light. Nature offered itself to my gaze in mourning.’[11] Here nature presents itself to the architect as a melancholic image—a shadow—suspended and detached from its own living presence. This led him to imagine a kind of architecture less of light and shadow than of shadow piled upon shadow: ‘a monument consisting of a flat surface, bare and unadorned, made of light-absorbent material, absolutely stripped of detail, its decoration consisting of a play of shadows, outlined by still deeper shadows’.[12]

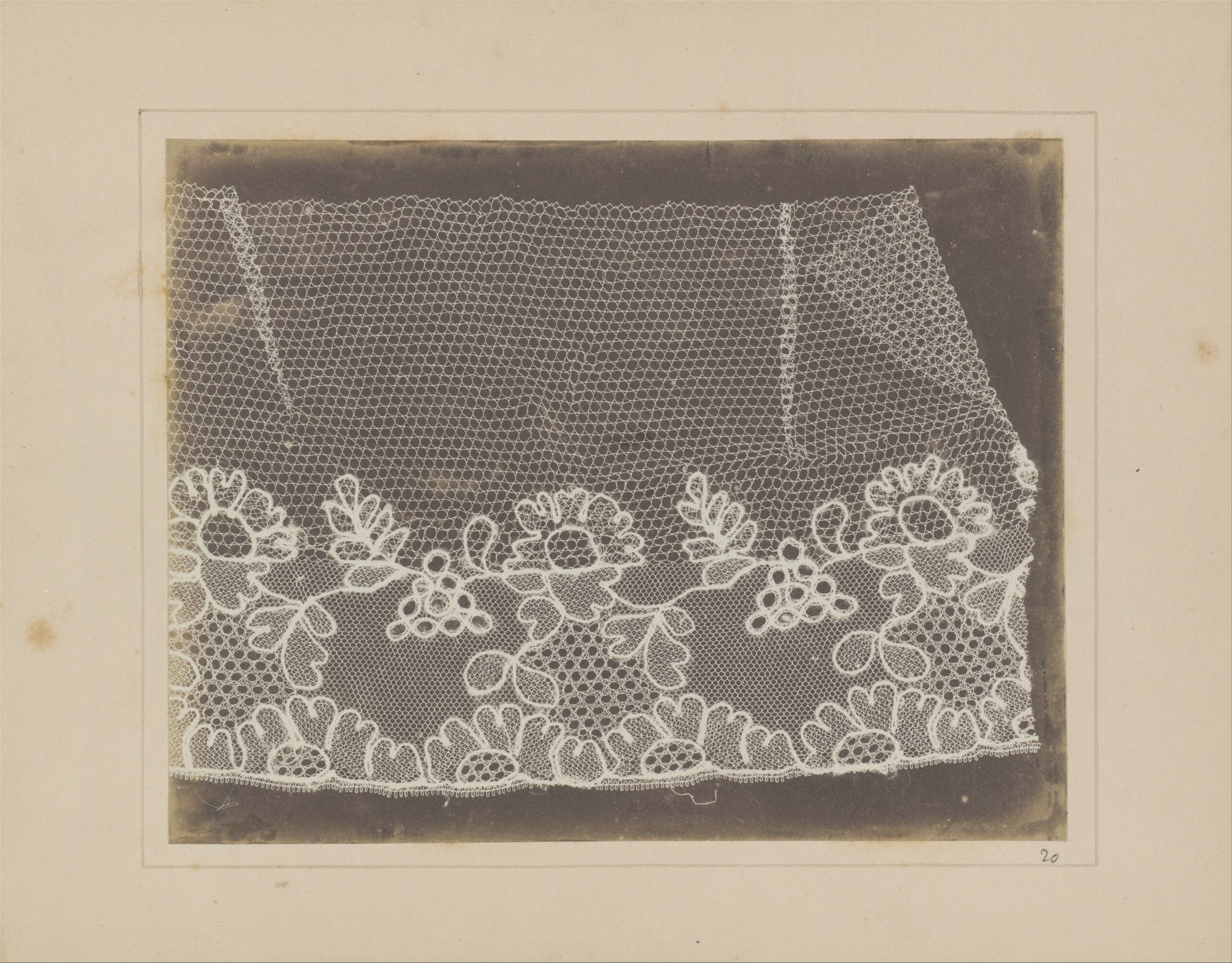

In his brilliant overview A Short History of the Shadow (London: Reaktion, 1997), Victor I Stoichita remarks on the experience of alterity that so insistently attends encounters with shadows. It is part and parcel of all imaginings and fantasies of detached shadows that gain a strange autonomy from the presences to which they are supposed to be subservient. Certainly, this is a peculiarly insistent modality of the shadow within modernity, no doubt impelled by the development of the ability to fix the photographic image—yet it is at the same time also very ancient. W.H. Fox Talbot’s initial photographic experiments (‘photogenic drawings’) with lace are obviously exercises in shadow detachment, while the daguerreotype process was advertised with the slogan ‘secure the shadow ere the substance fade’, a phrase that might equally be applied to the archaic act of shadow tracing described by Pliny. Across the surface of Marcel Duchamp’s Tu’ m’ (1918), flit anamorphic shadows cast by absent readymades.

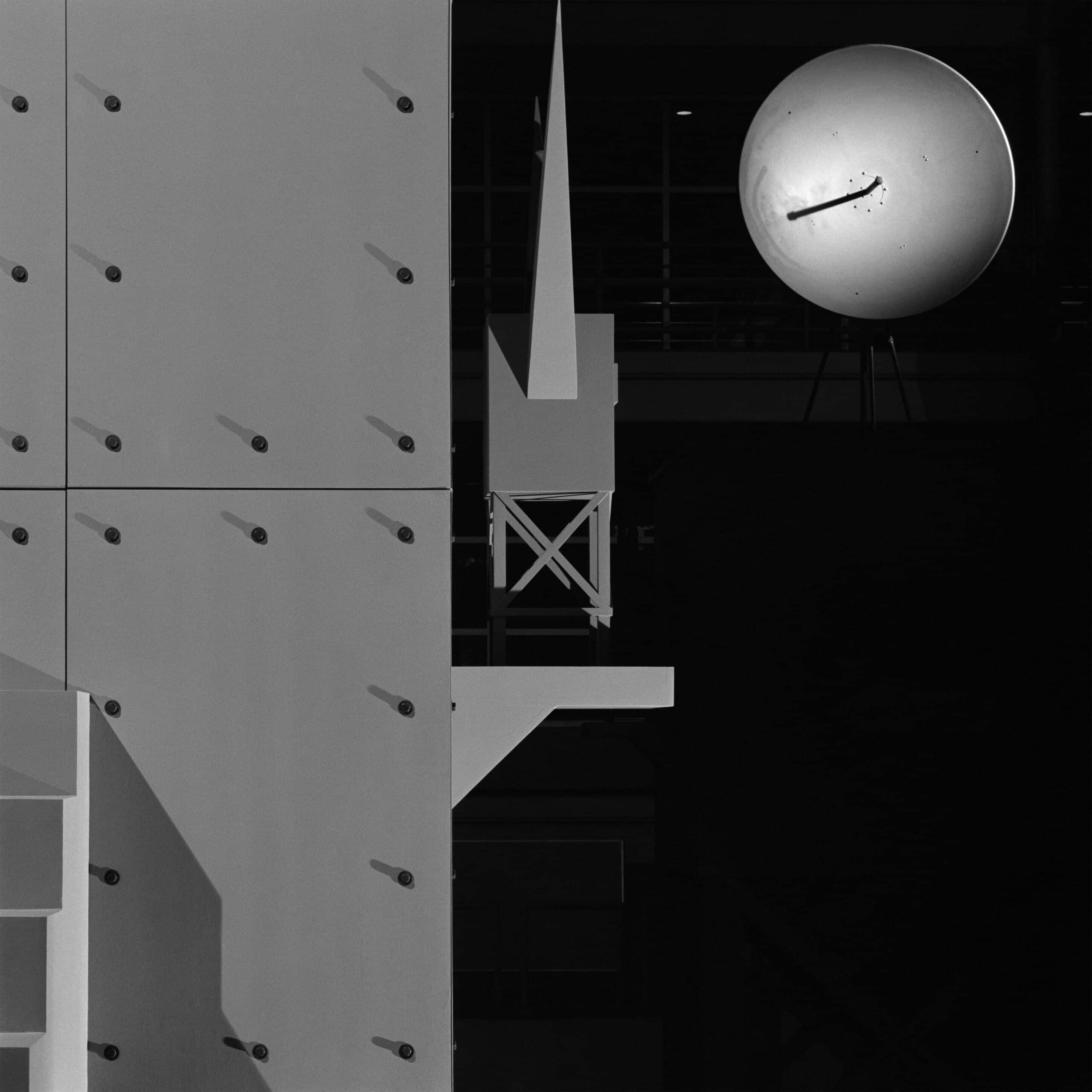

There are some contemporary architects who have a close association and affiliation with shadows which have taken on their own distinct and uncanny presences. The de Chiricoesque shadows of Aldo Rossi, who translated and introduced Boullée’s Essai, have an absolute and metaphysical value. They speak of a suspended time that recalls Michel Serres’ commentary on the story of Thales and that unites with many of the reflections in Rossi’s Scientific Autobiography: on painterly natures mortes; on the religious tableaux of the Sacri Monti; on the para-temporality of the theatre; on the arrest of the taxonomic specimen. ‘Once everything has stopped forever’, Rossi writes, ‘there is something to see’.[13] So too John Hejduk, who credited the encounter with Rossi’s work as re-orienting his own practice toward what he called ‘an architecture of pessimism’. Perhaps his relation to shadows is articulated most powerfully in an enigmatic photograph taken of his work Object/Subject by Hélène Binet.

In the photograph an abstract planarity is animated by shadows projected in an array of differing orientations, which indicate relief by themselves flattening onto surfaces. There is a somewhat similar effect in a renowned print of the Sixth Street House by Morphosis, which, in a play of doubling that suggests objects might even be the outcome of their shadows, restages the identity of shadow projection and orthographic drawing.

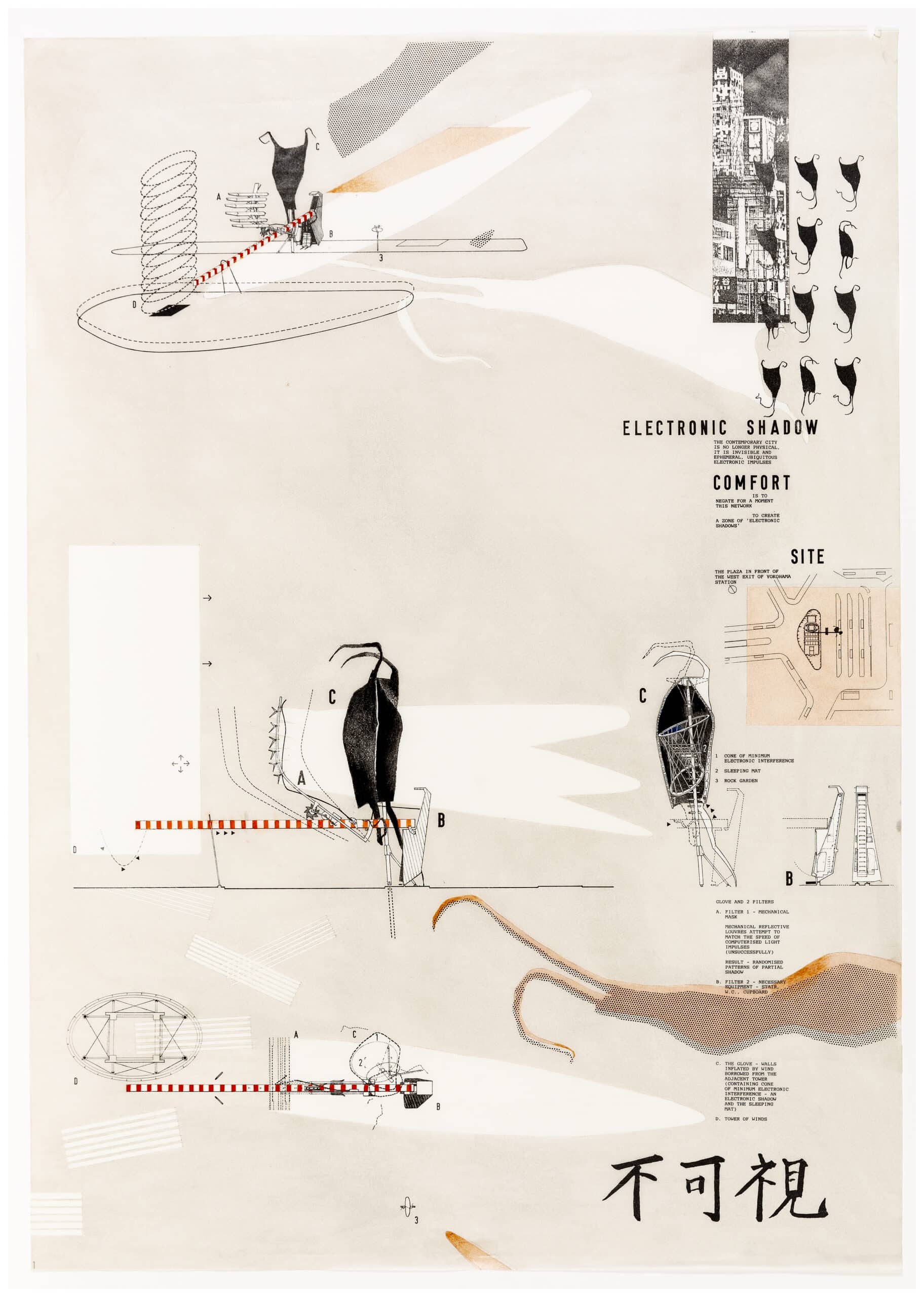

Peter Wilson is yet another architect whose work is marked by shadows. The exterior wall of his Suzuki House in Tokyo is imprinted with a black form that is understood as the shadow of a passing being. His celebrated entry for the 1988 Shinkenchiku Competition ‘Comfort in the Metropolis’ proposed an enigmatic black envelope—a refuge in the form of a soft object that acted as an electromagnetic shadow.

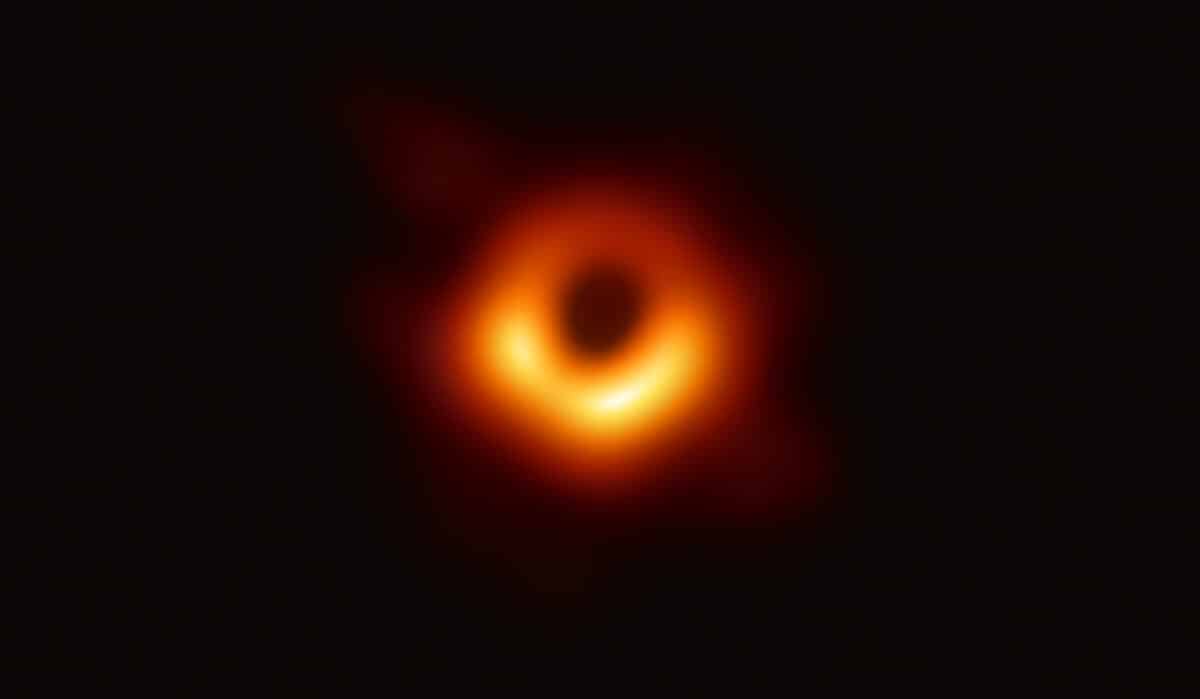

How do we see something that can’t be seen? Several years ago, the first ‘photograph’ of a black hole was published. The image was produced from observations made by the Event Horizon Telescope, an array of 8 observatories in 6 geographical locations operating across 4 days. As light cannot escape the massive gravitational pull of the black hole, it can only be imaged through light whose passage is warped as it moves around its edges. Peter Galison, the eminent historian of science who worked on the project, has said that the aim was to produce an image whose consequence could rival the famous ‘Blue Marble’ photograph of the earth, taken during the Apollo 17 mission in 1972. It is symptomatic of our contemporary conditions of image production that this was produced in a single ‘image capture’ event, whereas the black hole was painstakingly constructed using many data sets and with extensive and complex processing. In order to articulate what kind of image the black hole picture is, Peter Galison described it as a ‘silhouette’, which of course locates it in a tradition of shadow pictures. Seen in this way, the shadow shows us what can have no visual referent—it is a shadow whose detachment is absolute and unbridgeable. Maybe ‘silhouette’ is as good a characterisation as any available to us but, at the same time, it returns us to Pliny’s tale and associated ideas of the delineation of contour, which begs many questions.

This workshop invites participants to engage in thinking about shadows and image-making. It encourages reflection on what shadows do, how they have been conceptualised, their relation to different forms of media, and the way they operate in specific visual discourses. ‘Everything under the sun’—and more besides—lives with shadows and they come to orientate us in both space and time. They are deeply entangled with the development of our ideas about what image-making is and, more generally, have provided cultures with resources of almost incomparable imaginative fecundity.

Notes

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History, xxxv, 43.

- L.B. Alberti, On Painting and On Sculpture, ed. and trans. by Cecil Grayson (London: Phaidon, 1972), 47.

- ‘[T]he absence of an architectural setting in Schinkel’s painting is a recognition [that] the drawing must come before the building …’: Robin Evans, ‘Translations From Drawing to Building’, AA Files 12, Summer (1986), 3–18 (7).

- See the discussion in Francesco Javier Girón Sierra, ‘The Sun as Drawing Machine: Towards the Unification of Projection Systems from Villalpando to Farish’, Drawing Matter Journal 2, Drawing Instruments / Instrumental Drawings (2024), 206–232 (212).

- Thomas Da Costa Kaufmann, ‘The Perspective of Shadows: The History of the Theory of Shadow Projection’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, vol.38 (1975), 258–287 (265).

- Thales stops time in order to measure space … it becomes necessary to freeze time in order to conceive of geometry’. Michel Serres, ‘Mathematics and Philosophy: What Thales Saw …’, in Josué V Harrari and David F Bell, eds, Hermes: Literature, Science, Philosophy (Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982), 84–97 (87).

- ‘The true theme is an unseen banquet, as we can tell from the strewn litter. And this feast still seems to be going on … Moreover, some of the debris casts rather strange shadows as if it … has a little way still to fall. ’ James Davidson, Courtesans and Fishcakes: The Consuming Passions of Classical Athens (New York: St Martin’s Press, 1997), xv–xvi.

- Jean-Pierre Vernant comments: ‘It envelopes the whole head as if in a dark cloud; it masks it, and just as with someone who is dead, it makes the wearer invisible to all eyes.’ Jean-Pierre Vernant, ‘Death in the Eyes: Gorgo, Figure of the Other’, in From I. Zeitlin, ed., Mortals and Immortals: Collected Essays (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1991), 111–138 (121).

- Janis C Bell, ‘Zaccolini’s Unpublished Perspective Treatise: Why Should We Care?’, Studies in the History of Art, vol.59 (2003), 78–103 (81).

- Étienne-Lous Boullée, ‘Architecture, Essay on Art’, in Helen Rosenau, Boullée & Visionary Architecture (London: Academy Editions, 1976), 81–147 (90).

- Ibid., 106.

- Ibid.

- Aldo Rossi, A Scientific Autobiography, trans. Lawrence Venuti (Cambridge MA and London: MIT Press, 1981), 47.

*

Mark Dorrian is Editor-in-Chief of Drawing Matter Journal, holds the Forbes Chair in Architecture at the University of Edinburgh, and is Co-Director of the practice Metis. His work spans topics in architecture and urbanism, art history and theory, and media studies. Dorrian’s books include Writing On The Image: Architecture, the City and the Politics of Representation (2015), and the co-edited volume Seeing From Above: The Aerial View in Visual Culture (2013).