Eurolandschaft Dérive

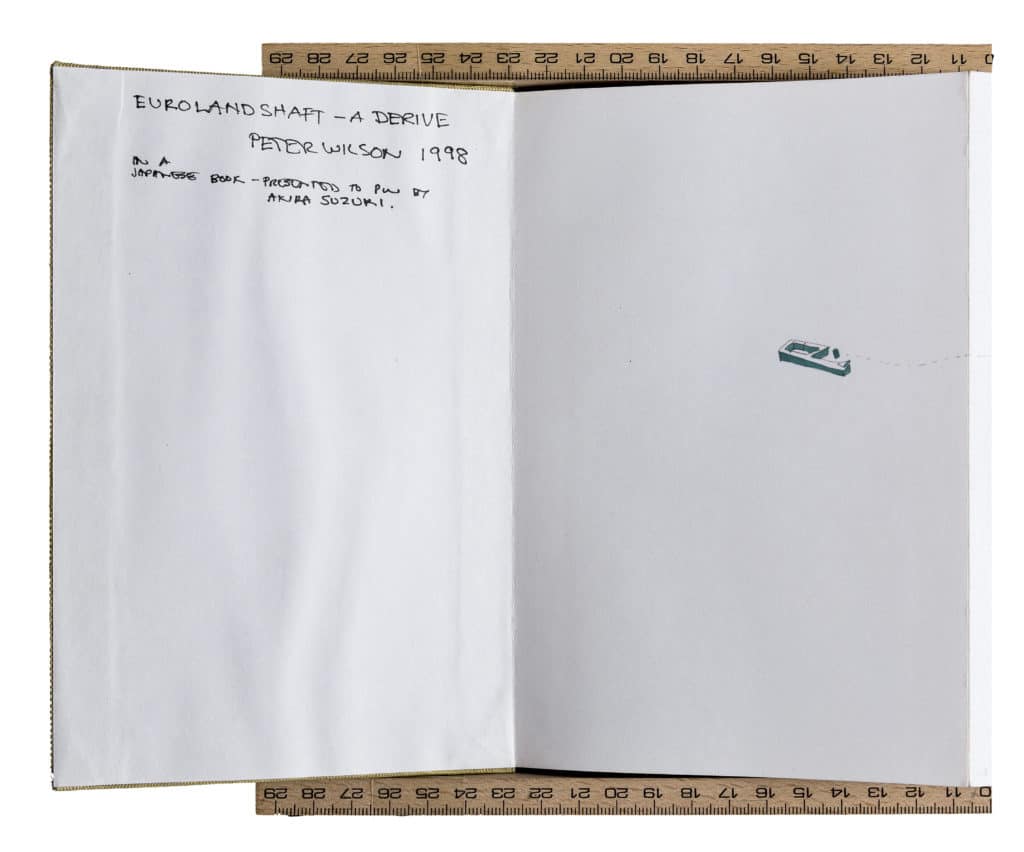

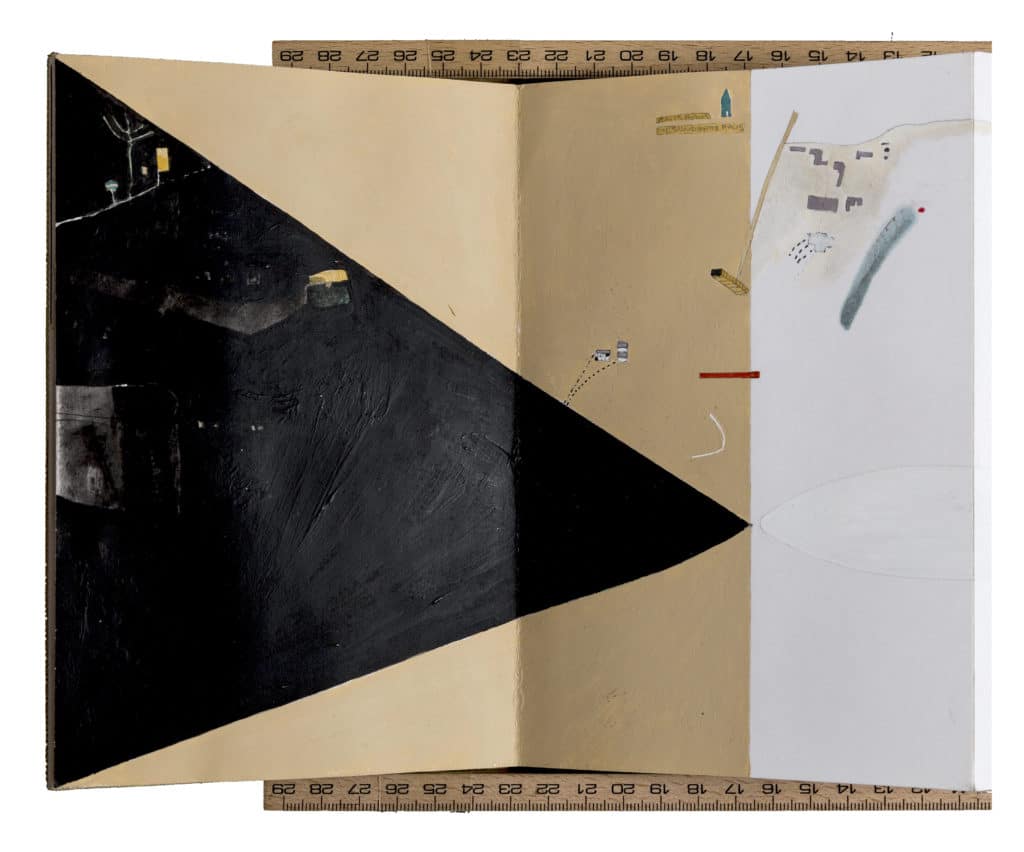

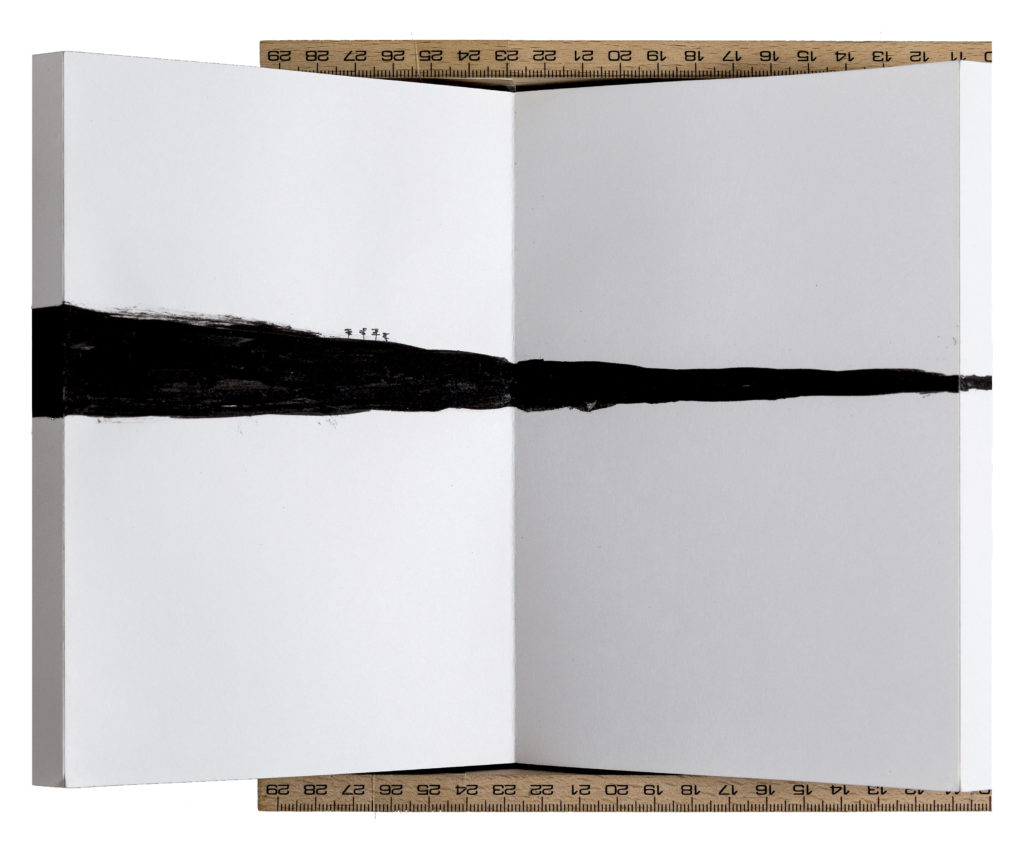

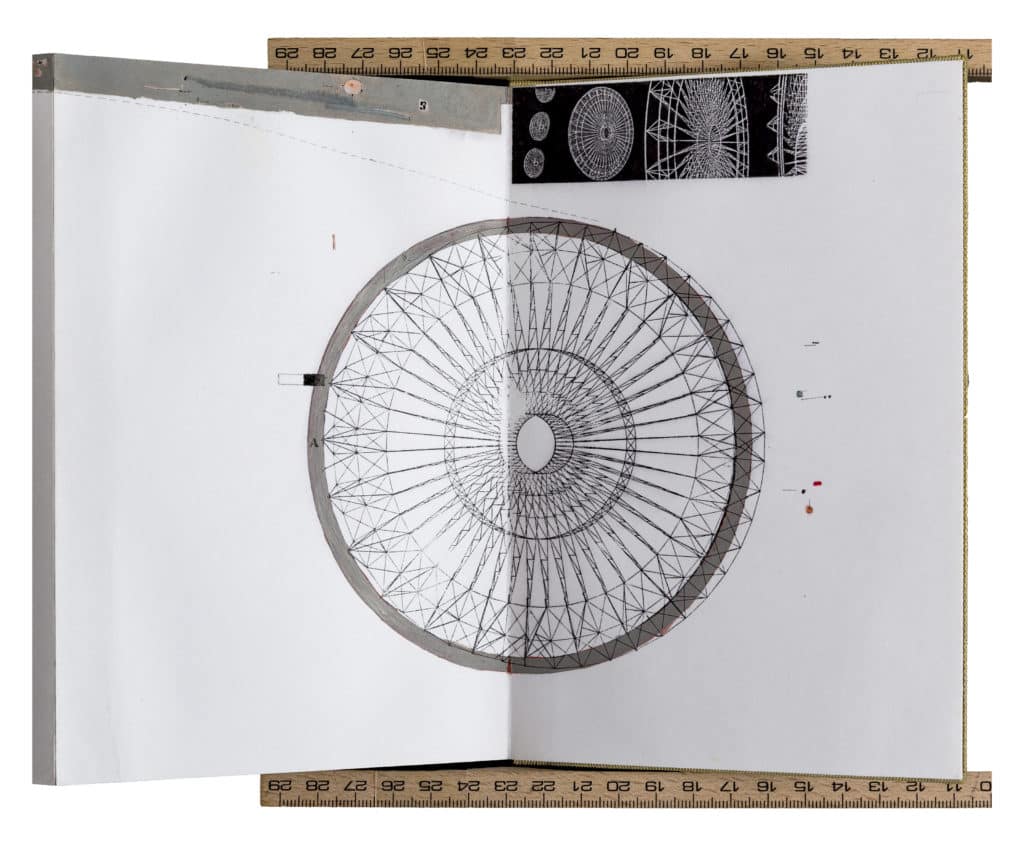

The format is Japanese: a concertina sketchbook presented empty to me by Akira Suzuki shortly after the 1983 completion of our Tokyo Suzuki House design.

The drawing format is also Japanese – influenced by our reading of Tokyo (documented in Western Objects + Eastern Fields, AA 1989).

Tokyo is difficult for us gaijin to grasp; it does not fit in a Western hierarchical template. We read it as a cloud of autonomous events, each a monad: air conditioner, dog monument, private house, department store, fun park, vending machine, temple.

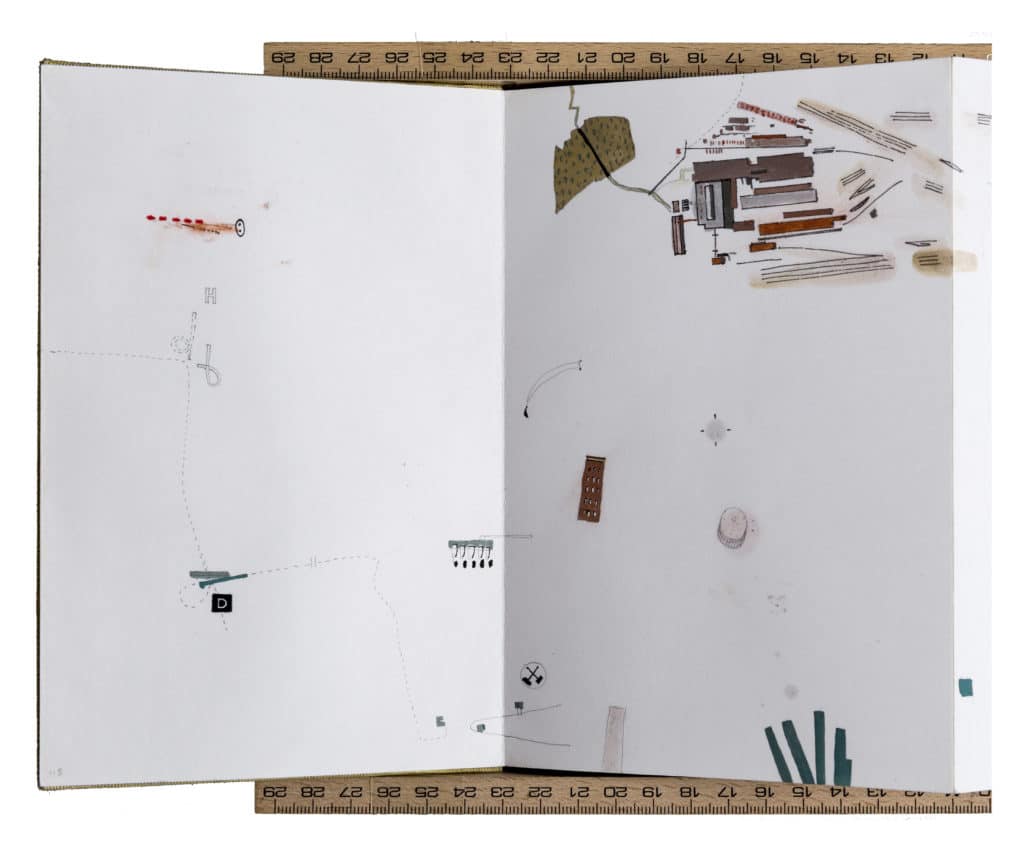

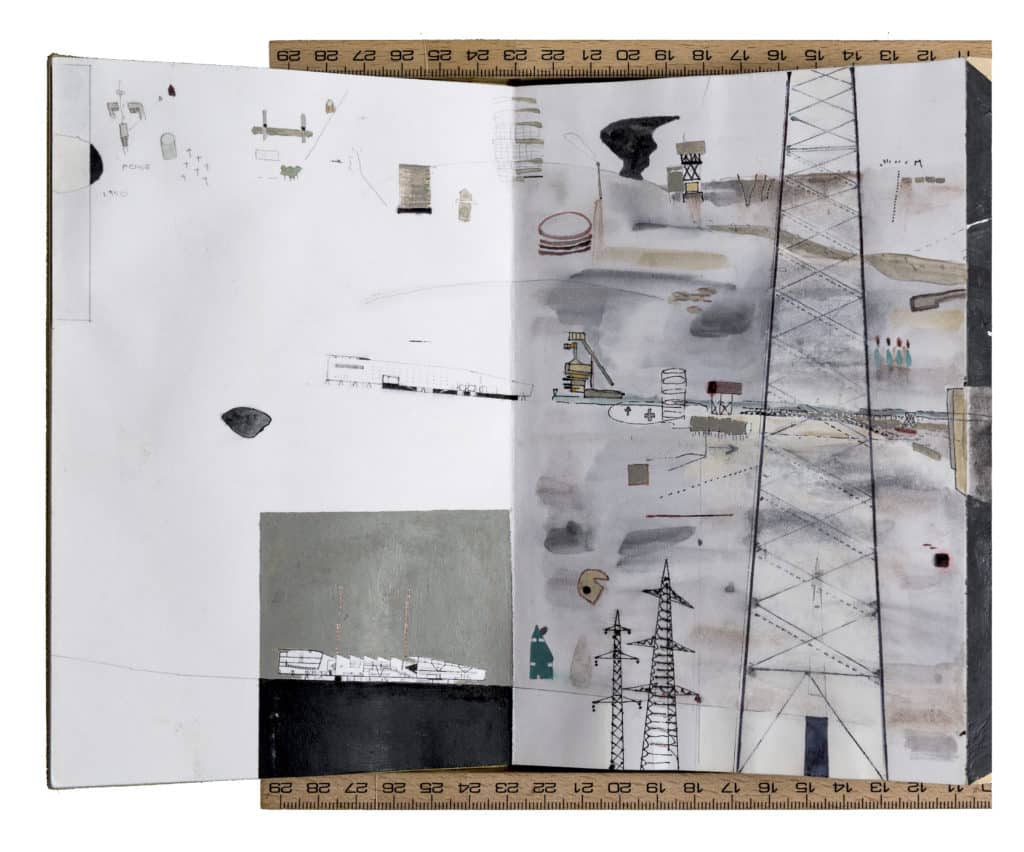

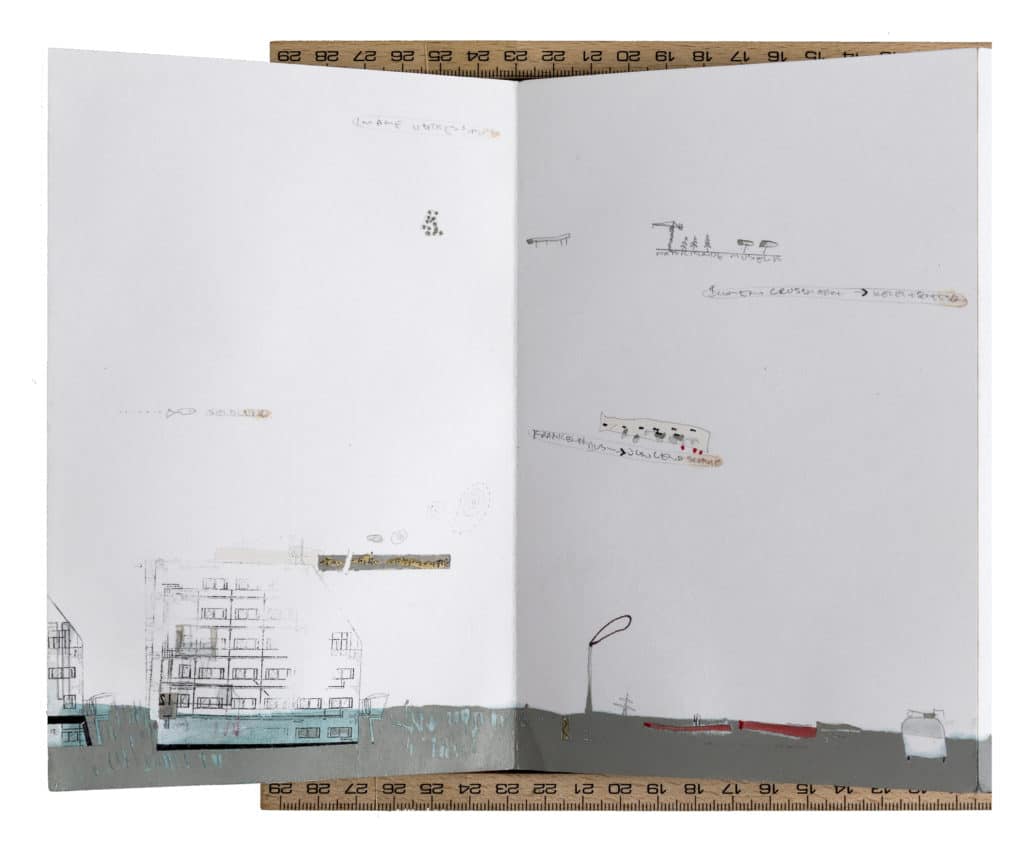

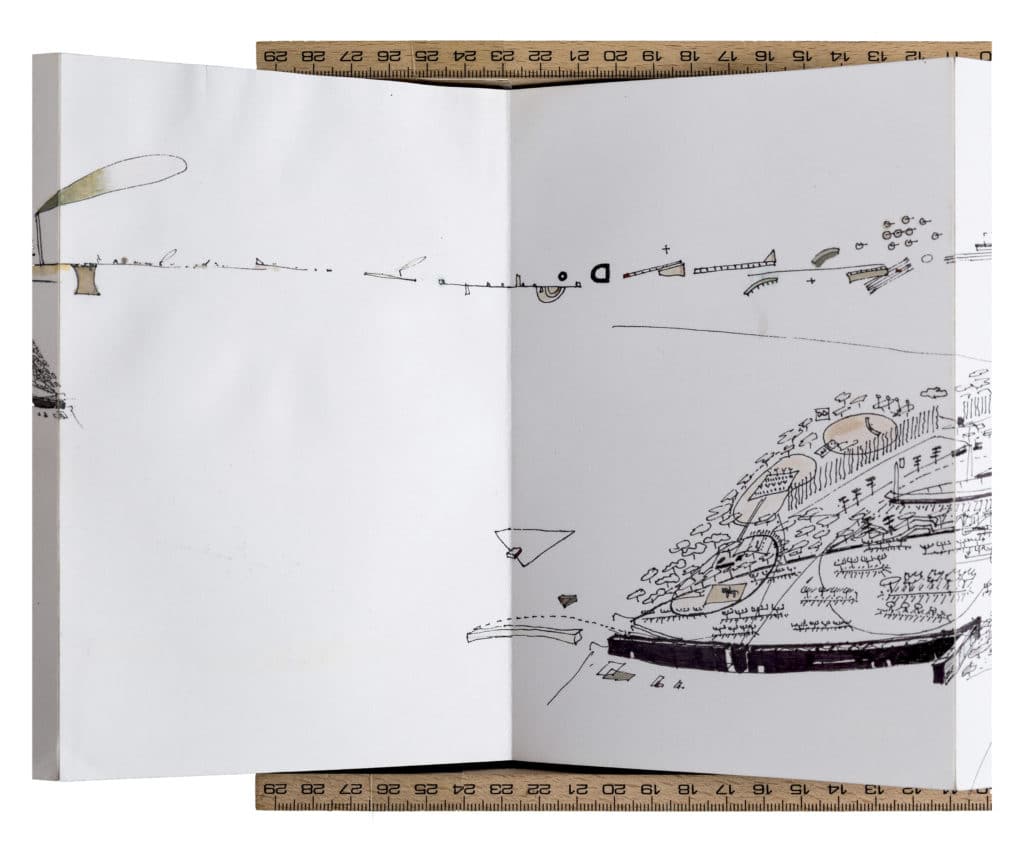

Some ten years after our Tokyo dérive we found ourselves in Germany, crisscrossing a landscape that was not in the historic sense city, yet also not country: a low-density urban network spread across the entire European landscape, from the Mediterranean to the North Sea. It was a thinned-out version of the Tokyo soup model, except here the monads were: derelict industry, out-of-town shopping centre, business park, sporadic suburban bungalows, a wind generator, biotope, gas station, graffitied bridge, allotments, big-box shed, freeway exit. The last is significant because the whole matrix only works because of the just-in-time delivery systems, a lack of proximity legitimated by digital communication. We called this condition the Eurolandschaft (Euro-landscape).

In the intervening years, it has fallen under and out of the spotlight of theoretical coolness/interest.

Rem refers to it as Junk City, and Tom Sieverts has theorised it as Zwischenstadt (Between City). In Italy it goes under the name of ‘La Città Difusa’ and elsewhere as The Concrete Babylon.

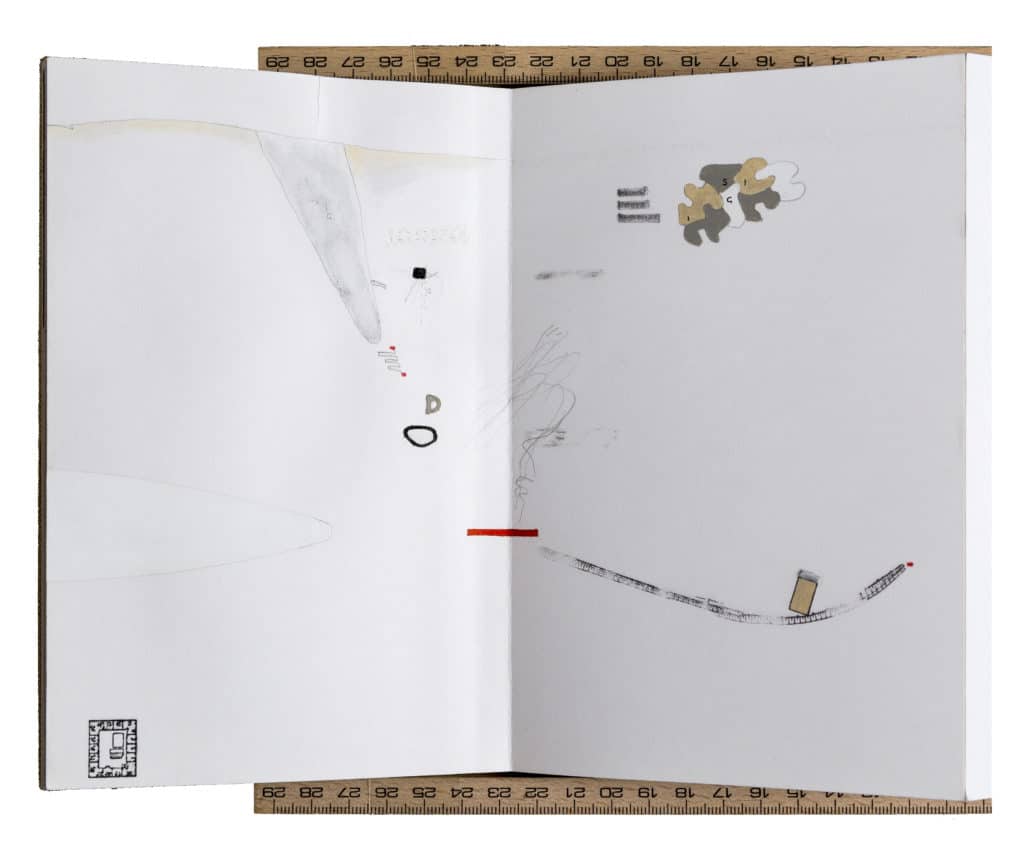

It is a virus. Uncontrollable and uncontainable with conventional planning tools, it requires instead whole new representational modes, and a whole new vocabulary: intermedial exchange, organisational batches, subtraction versus tabula rasa, temporal markers, ecologies of circuitry, operatives of active organisation, networking protocols, tactical sites.

We at BOLLES+WILSON were much criticised by our ‘Historic-city-reconstructing-colleagues’ for toying with this devilish mutant, and yet its melancholic ambience on a grey winter’s day was not without poetry. It is this discontinuous spatial experience that the Japanese foldout sketchbook tries to summarise and render graphically.

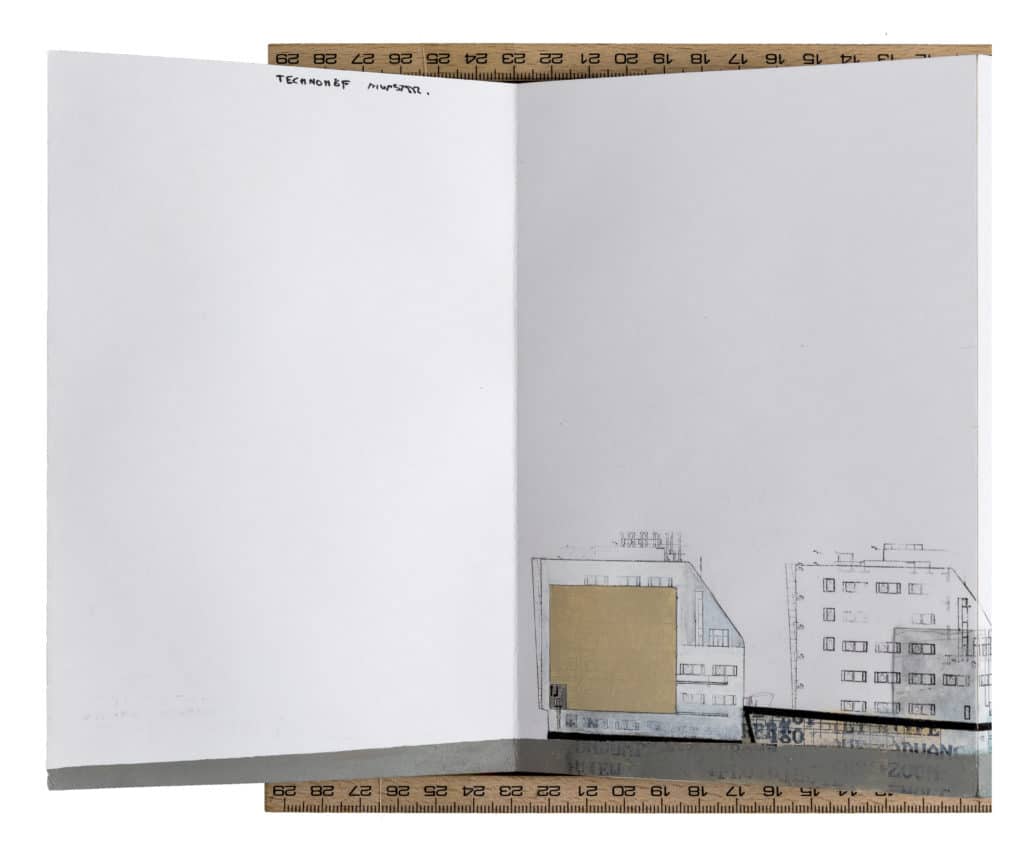

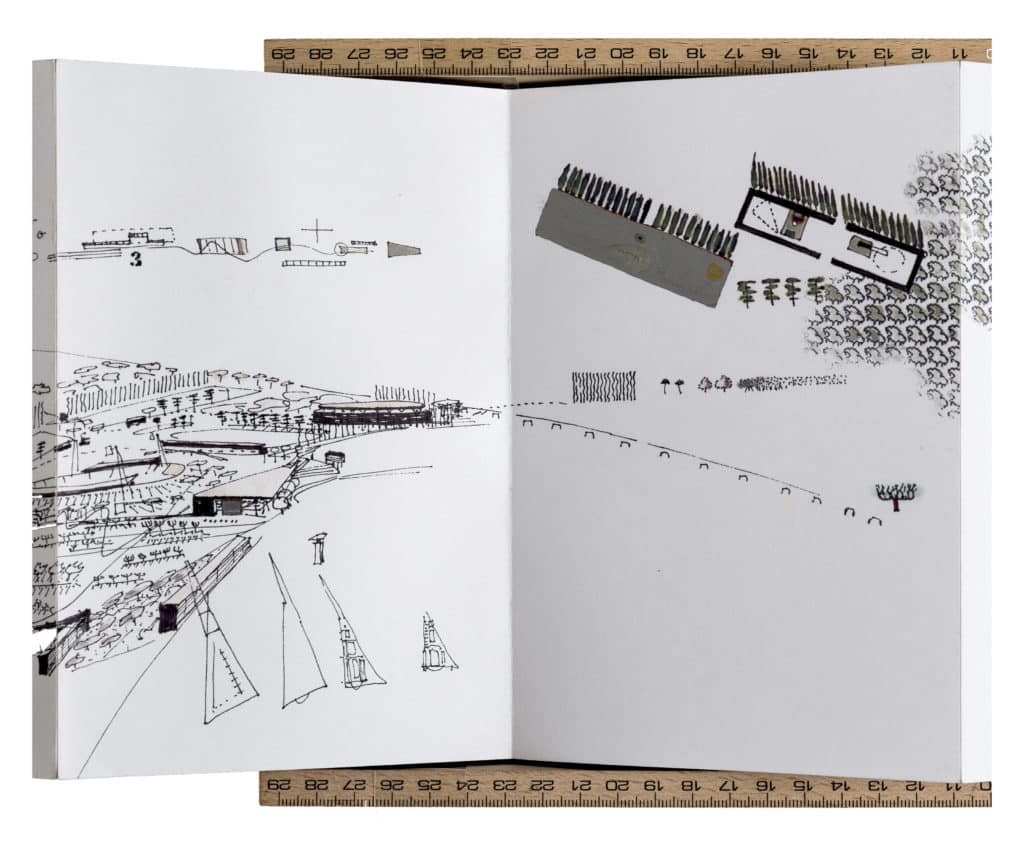

Near the beginning of the fold-out sequence are images of one of the first stones we threw into the Eurolandschaft pond: three compact laboratory buildings. Insistent on their autonomy (anchors in the field) and their disconnectedness, they float in a bucolic landscape that we enhanced by planting an apple tree orchard across the site.

High-voltage masts and the noble industrial giants of the Ruhr make walk-on appearances among the concertina folds.

The graphic system slips from architectural convention to numeric indexation to somewhat heavy-handed taxonomies of the moving viewer.

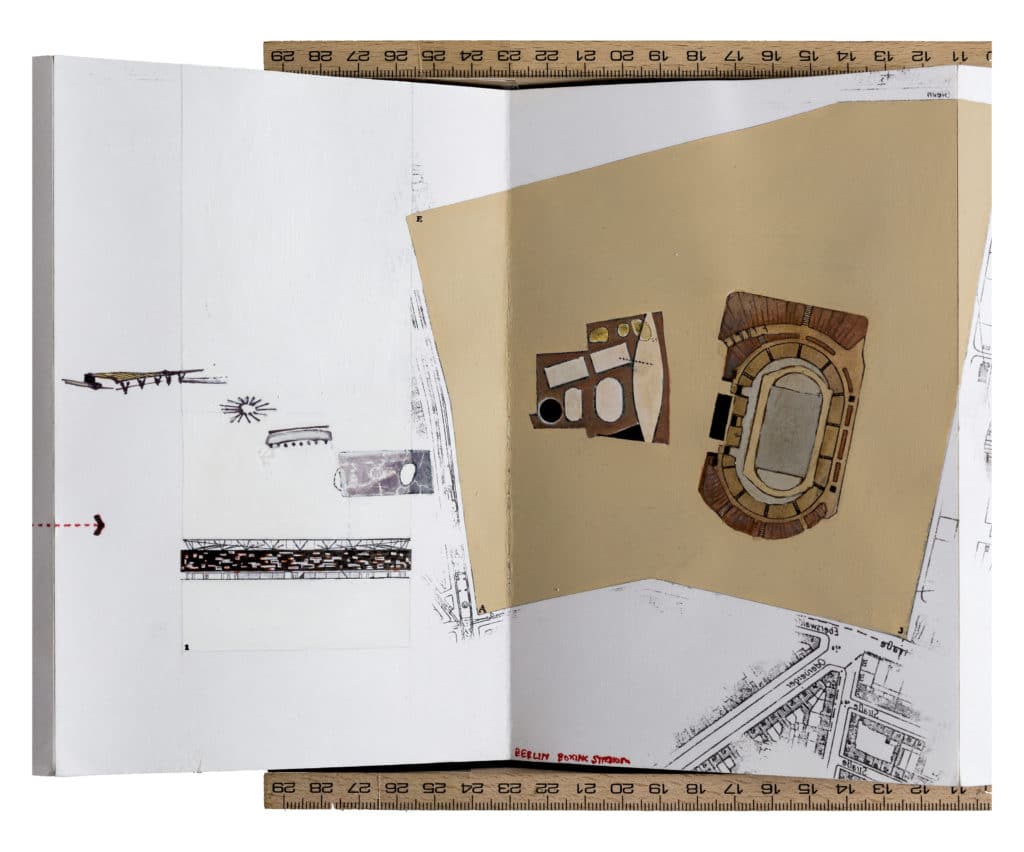

Near the end a circular boxing stadium (competition second prize) lands in the no man’s land that was, not long before, the Berlin wall.

The strategy that resulted from such dérives was one of peppering, the pumping-up of programmes to become mega-objects – anchors that, like cooling towers, give measure and architectural legitimisation to a topography that is too often and too easily seen as a planning disaster.

The fold-out book is evidence of research – territorial and perceptual research outside the cannons of conventional planning.